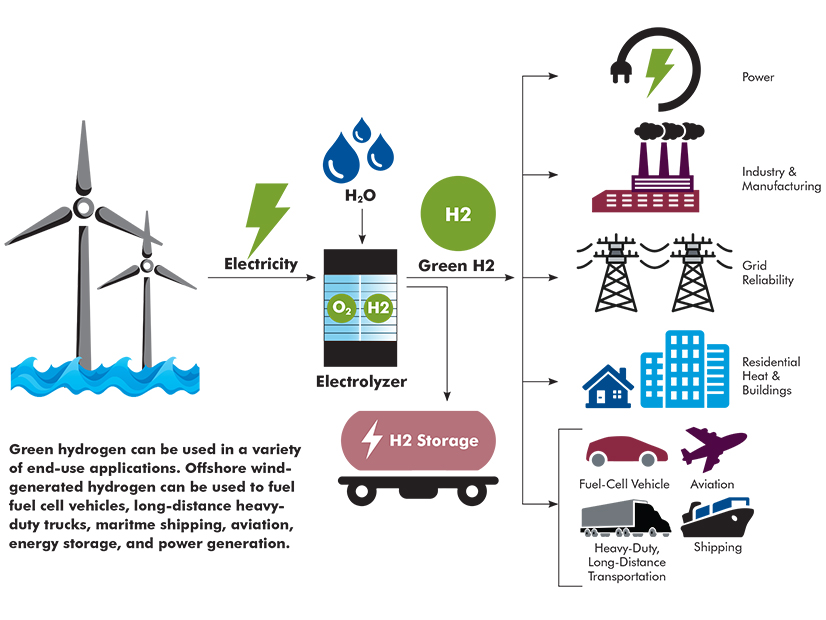

The Clean Energy States Alliance, a national association of state agencies, is urging states that will have access to considerable power from offshore wind turbines to consider allowing industry to dedicate some of that electricity to produce renewable, or “green,” hydrogen.

In a report issued in October and promoted recently in a webinar, CESA examined what European governments and companies are already considering and then looks at the feasibility of doing the same in the U.S.

Europe, with an already mature offshore wind industry and a commitment to decarbonize its economy, is looking seriously at replacing natural gas with hydrogen.

And offshore wind power, according to CESA and in other discussions, is being considered as the best source to power large electrolyzers that strip hydrogen out of water. The price of offshore wind is already falling and expected to further decline as larger projects proliferate, the report notes.

Wind projects in Europe, for example, are now transitioning to turbines that generate 12 MW, especially those very large projects being built or planned further offshore. Future projects will be measured in gigawatts. These developments are leading to economies of scale, lowering the price per megawatt-hour.

Another factor that further lowers prices is that turbines operate at a higher capacity factor; that is, they are able to operate at a higher percentage of time on any given day, generating more total power.

Finally, it appears that offshore power projects are expected to proliferate globally.

“The installed capacity of offshore wind is expected to quadruple globally over the next decade, growing from a cumulative installed capacity of around 50 GW in 2021 to 225 GW in 2030,” the report notes. “Approximately 50% of total offshore wind capacity in the world will be in Europe in 2030; Asia will account for roughly 40% of global installed capacity, and the U.S. for the remaining 10%.”

Warren Leon, (left) executive director of CESA and moderator in a CESA-produced hydrogen webinar questioned whether there are downsides to using wind energy to produce hydrogen from water. Val Stori, a CESA project director, said electrolyzers that use power to break apart the hydrogen and oxygen atoms in water are inefficient, meaning most of the energy used to make hydrogen is lost. Lee Wilkinson, a UK-based consultant, said European nations want to replace natural gas with hydrogen for industrial uses. But to be competitive, wind energy used to make hydrogen must be significantly lower priced that it is now, he said. | Clean Energy States Alliance

Warren Leon, (left) executive director of CESA and moderator in a CESA-produced hydrogen webinar questioned whether there are downsides to using wind energy to produce hydrogen from water. Val Stori, a CESA project director, said electrolyzers that use power to break apart the hydrogen and oxygen atoms in water are inefficient, meaning most of the energy used to make hydrogen is lost. Lee Wilkinson, a UK-based consultant, said European nations want to replace natural gas with hydrogen for industrial uses. But to be competitive, wind energy used to make hydrogen must be significantly lower priced that it is now, he said. | Clean Energy States Alliance

Lee Wilkinson, a senior consultant at UK-based BVG Associates and a consultant on the CESA study, summed it up this way: “A key reason why Europe is looking at hydrogen is that many people see it as a good replacement for natural gas. As soon as you say … we want to use hydrogen in our energy system, now you’ve got to find the best places to get it. And for many European countries, that’s wind.

“Europe has very good offshore wind resources that they have begun to capitalize on. So there’s a link between hydrogen and offshore wind, where Europe can start to make a connection on how [to] decarbonize more of its energy system.

“There are a few more subtleties to that. The first one is to get the cost of hydrogen down [and] keep the costs low, it’s best to produce hydrogen at scale. One benefit of offshore wind is that it is very good at being deployed at scale. Many wind farm has been deployed today in excess of 1 GW.

“Compared to other sources of renewable electricity like onshore wind and solar, you can get larger economies of scale if you power up your hydrogen production with offshore wind,” he said.

Big oil companies are also moving into offshore wind, he said, further building momentum for hydrogen production, as it somewhat resembles fossil fuels.

But a U.S. leap to hydrogen may not be as easy as it might initially appear. Not only did European offshore wind begin two decades ago, many European nations are already committed to decarbonizing their economies.

“One of the reasons we wrote this report is we wanted to advise U.S. policymakers, particularly states, as to what and how they should be thinking about hydrogen. There are some really big differences between where Europe is and where the U.S. is,” said Val Stori, CESA project director and author of the report.

“And I think one of the big ones is that Europe and the European states have legally binding targets to achieve carbon emission reductions. Significant ones, net-zero ones: 55% by 2030, compared to 1990 at the EU level.

“So … some of the most ambitious decarbonization targets in the world are in place in Europe. In addition, you have an offshore wind energy industry that is mature and is growing and costs are declining rapidly. So 70 GW of offshore wind projects are expected to come online in Europe by 2028 and 300 GW by 2050. That’s huge compared to where we are in the U.S.”

Getting the price of offshore wind down is based on another factor, said Stori: Today’s electrolyzers are inefficient. “That means a large portion of the renewable energy that we’re pouring in to make green hydrogen is lost upwards of 82%” across the full cycle of production and use, she said.

Noting that U.S. offshore wind is in its infancy, the report concluded that powering electrolyzers with wind energy is a use that probably should be considered in the future rather than immediately.

“It may ultimately make sense to use some of the offshore wind output in the United States for green hydrogen production. However, offshore wind in the U.S. is at a much earlier stage of development than offshore wind in Europe. For at least the next decade, the output from U.S. wind farms will be fully needed for electricity production that displaces fossil-fuel generation. That electricity will be especially valuable because the wind farms will be relatively close to major load centers,” the report concludes.