Hydrogen emerged as one possible solution to climate change during the recent 26th U.N. Climate Change Conference of the Parties, but details of the transition to the fuel were sketchy, leaving the door open to competing solutions.

What was clear even before the historic conference is that hydrogen research has been underway for some time and that moving away from energy-dense oil, coal and natural gas would be as consequential as the switch from burning wood to coal at the start of the industrial revolution.

The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a non-partisan think tank founded to address national security issues, has been focusing on what that transition might look like, including the underlying economy necessary to support such a change.

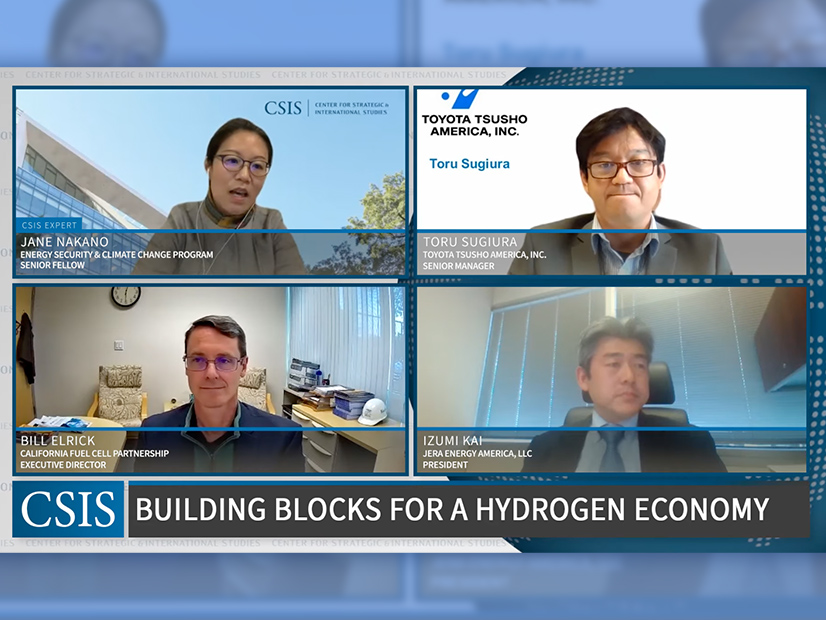

CSIS has hosted a series of energy webinars on the topic, the most recent of which examined the “building blocks for a hydrogen economy.” The discussion was sponsored by Japan House of Los Angeles.

Moderated by Jane Nakano, a CSIS senior fellow heading the security and climate change program, the Nov. 16 discussion focused on:

- efforts in California to expand the current fleet of 100 fuel cell buses and more than 10,000 fuel cell cars and light trucks already on the roads and expand the network of hydrogen fueling stations;

- plans to begin switching a small number of the nearly 3,000 diesel and gasoline trucks and unloading equipment at two major California ports to either fuel cells using hydrogen or batteries charged on the local distribution grid;

- efforts in Japan to burn anhydrous ammonia (NH3) with coal at power plants and ultimately modify gas turbine power plants to operate with hydrogen — and importing all that hydrogen or ammonia through a global supply chain still under development.

Fueling the FCEV Fleet

Bill Elrick, executive director of the California Fuel Cell Partnership, said fuel cell electric passenger cars and light trucks would provide the foundation for building a hydrogen refueling system for heavy trucking.

His organization launched a retail-oriented hydrogen market about six years ago, opening hydrogen refueling stations, typically at gas stations already in business. The point was to convince potential owners of fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) that they would have a steady supply of hydrogen. Now they want to expand the system in order to increase the light-duty FCEV fleet.

“By achieving that light-duty market, we see it lowering the cost not just for that market, but [lowering] hydrogen infrastructure and fuel cell technology costs for other applications and even other regions,” he said.

Whether EVs are powered by batteries or fuel cells is not as important as what fuels them, he added. Both hydrogen and electricity stored in batteries are 100% carbon-free.

Toru Sugiura is a senior manager at Toyota Tsusho America, a Kentucky-based subsidiary of Toyota Tsusho, a global trading company dealing in metals, automotive parts, chemicals, food and fuels. He said his company has been working to develop the kind of hydrogen supply chain that Elrick described.

“We operate hydrogen stations in Japan,” Sogiura said. “That is currently a challenging business model for economic viability by simply waiting for customers to come.”

In California, the company is about to begin a demonstration project, supported by several federal grants to create hydrogen from methane produced from cow manure and then deliver that gas to the Port of Los Angeles, where efforts are underway to switch out diesel-powered equipment with that powered by fuel cells.

“By making the whole value chain together as one business model, we are trying to create a supply and demand [and] at the same time a self-sustainable supply chain from upstream to … [down]stream,” Sugiura explained.

He said the company has held extensive discussions with terminal operators at the Port of Los Angeles and at Long Beach, about 25 miles away.

The two ports are home to 13 shipping container terminals. The nearly 3,000 trucks, gantry cranes and other cargo handling equipment, powered by diesel or gasoline engines, operate around-the-clock at the terminals.

The company has developed a mobile fueling station that will deliver the renewable hydrogen to the terminal equipment powered with fuel cells, he said.

A related company, Toyota Motors, has partnered with truck maker Kenworth to build 10 fuel cell terminal trucks, now operating at the ports.

“Port terminals have determined a very clear goal of zero emission. The equipment must be 100% zero-emission by 2030 and … the trucks that must be-zero emission by 2035,” Sugiura said.

“There are many challenges to overcome for this technology transition from diesel to hydrogen in the port area. The first one is hardware commercialization by the [original equipment manufacturers]. So we work closely with the OEMs to promote the development and also the actual manufacture of the equipment.

“Another obstacle is that currently only the Port of Los Angeles will require the fuel cell-powered equipment.”

Finally, fuel cell trucks are more expensive than diesels. And hydrogen is more expensive at this point than diesel fuel, he said.

Even if the demonstration is successful, moving to mass production of hydrogen and full commercialization of fuel cell trucks will be a challenge, Sugiura said, including regulatory issues that must still be worked through.

Hydrogen fueling protocols and fire code permits will be critical, he said. “This is a slow process, so we are working closely with the government and related authorities.”

Room for Both

CSIS’s Nakano asked whether it would make more sense to rely on batteries rather than fuel cells.

“We need both of them because they both have strengths and weaknesses that actually match each other,” Elrick said. “Just like neither diesel nor gasoline dominated everything in either market, but they found where they worked best.”

“I think we’re going to find that generally and in transportation especially,” he continued. “And I don’t think it’s out of place to say the heavier applications will clearly play with the advantages of hydrogen more, where batteries, on weight alone, can be one of the disadvantages.

“But in the light duty, especially in the urban communities, we will see more battery vehicles because they don’t go as many miles and that’s a really nice niche for them. But I also think there will be a lot of overlap.”

Izumi Kai, president of Houston-based LNG company JERA Energy America, a subsidiary of Japan’s largest electric power producer, said LNG will remain important for the next two to three decades, especially in developing countries.

He said JERA wants to blend ammonia with coal at its most efficient coal-fired power plants with the goal of completely replacing coal. Similarly, the company hopes to begin to switch its gas turbine power plants to 100% hydrogen by co-firing hydrogen and natural gas. (Anhydrous ammonia is a gas but turns to liquid at -28 degrees Fahrenheit.)

“But it takes 20 years or so, to achieve a full replacement … to enable such co-firing. It is very difficult to be responsible for a stable energy supply and also a competitive energy supply,” Kai said.

Japan now imports its LNG but in the future hopes to import ammonia because it is easier to transport, he added, and it can be converted to hydrogen at its point of use if necessary.

Asked by Nakano whether carbon pricing or the creation of a carbon market might speed up the development of hydrogen as a fuel, all three panelists agreed it would.

Kai said Japan and other Asian nations, which will be importing low carbon fuels, would especially benefit.

“It’s important to have some kind of government support or some kind of commercially viable mechanism. A carbon credit system is one of the key options,” he said.

Sugiura, whose company wants to electrify the Port of Los Angeles, agreed. “In order to make hydrogen a common fuel, I think it’s very important that we start using hydrogen, whatever the color,” he said, adding that hydrogen would be become a “common fuel” if given a credit in a federal carbon market.

And Elrick, whose organization is poised to go national in its advocacy of hydrogen fuel cells, said decarbonizing the fuel is equally as important as switching to FCEVs.

“If we changed every car, or vehicle, if we changed every heat pump and every stove to zero emission, it doesn’t necessarily mean that fuel, whether hydrogen or electricity, was decarbonized,” he said.