North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper on Thursday vetoed a bill that would have prohibited the state’s cities and counties from banning natural gas hookups in residential construction.

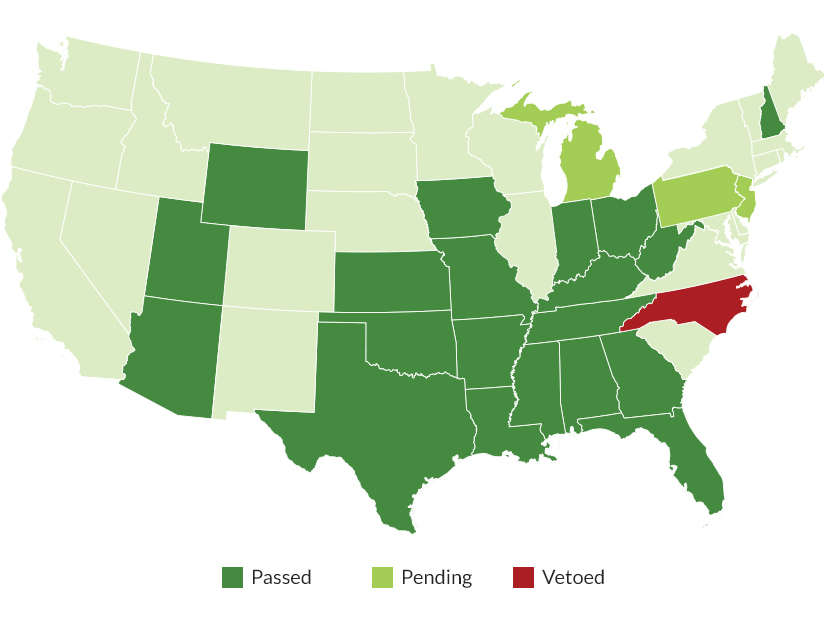

To date, similar bills — heavily supported by the natural gas industry — have been passed in 20 states and are pending in four more. These “pre-emptive bills” have all been enacted in the past two years in response to ordinances or building codes now adopted in 50 cities in California to promote home electrification and reduce carbon emissions by banning natural gas hookups in new construction, according to S&P Global.

In a statement released with the veto announcement, Cooper said, “This legislation undermines North Carolina’s transition to a clean energy economy that is already bringing in thousands of good paying jobs. It also wrongly strips local authority and hampers public access to information about critical infrastructure that impacts the health and wellbeing of North Carolinians.”

The governor has been pushing for the state to cut its emissions by 70% over 2005 levels by 2030, a goal codified in a new law, HB 951, which he signed in October. According to a 2019 greenhouse gas inventory produced by the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, residential emissions then accounted for 3.5% of the statewide total.

The vetoed bill, HB 220, would stipulate that cities and counties in the state cannot “adopt an ordinance that prohibits, or has the effect of prohibiting, the connection, reconnection, modification or expansion of an energy service based upon the type or source of energy to be delivered to an individual or any other person as the end user of the energy service.”

The specific sources of energy that cannot be prohibited are defined in the bill as “natural gas, renewable gas, hydrogen, liquefied petroleum gas, renewable liquefied petroleum gas or other liquid petroleum products.”

To date, no North Carolina cities or counties have passed or proposed such bans, which led some Democratic lawmakers to question the need for the bill when it was introduced earlier this year. Defending the pre-emptive action, Rep. Dean Arp (R), a bill sponsor, said, “Energy policy is a state issue,” and a bill protecting consumer choice “absolutely clarifies that before it becomes a problem.” (See Gas Industry Brings Fight Against Building Electrification to NC.)

In a statement released following Cooper’s veto, Arp said the bill was intended to leave “household decisions like whether or not to have a gas stove in their home to consumers themselves. The heavy hand of government has no place in the personal decisions North Carolinians make for their households.”

House Speaker Tim Moore (R) also criticized the veto, characterizing it as an act of “partisanship over common sense.”

To override a veto, a three-fifths majority is needed in each chamber of the General Assembly: 30 votes in the Senate and 72 in the House of Representatives. There are 28 Republicans in the Senate and 69 in the House.

‘It’s not About Today’

Maggie Shober, research director at the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy, praised Cooper for “standing up for local control of how to make our buildings safer and cleaner. These ban-the-gas-ban bills have been pushed by special interests across the country, with little thought to the customers that will be forced to pay for expanding fossil fuel infrastructure in their neighborhoods while the science has been clear: To avert the worst of climate change, we need to reduce, not expand, our use of fossil fuels.”

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, about one in four North Carolina homes are heated with natural gas. EIA also ranks the state as one of 10 in the U.S. with the lowest per capita use of natural gas, although natural gas consumption there has quadrupled in the past decade, mostly from its use in electricity generation.

But the debate here and in other states has centered on the economics and emissions of natural gas versus electricity.

The American Gas Association does not take positions on state policies, such as pre-emptive laws prohibiting bans on natural gas hookups, but spokesperson Jake Rubin argued that natural gas is both a cheaper, cleaner and more reliable fuel for home heating and cooking.

“A natural gas home has fewer CO2 emissions than a home that uses electricity for its various applications … because of the efficiency of the delivery infrastructure,” Rubin said. “It takes a lot more energy to get electricity to a home than it does to get natural gas to a home.”

And because “most of electricity is made using either coal or natural gas,” he said, a home using natural gas for space and water heating and cooking will have lower emissions than an all-electric home.

But Ram Narayanamurthy, program manager for buildings at the Electric Power Research Institute, said that calculations of an electrified home’s emissions will depend on the generation mix of the utility providing the electricity. And, he noted, many utilities are now committing to decarbonizing their power supplies.

“We find that in places like California, the generation mix they have today, all-electric homes [produce] about 40% less emissions than a mixed-fuel home,” he said. “In a place like Texas, it’s closer to neutral.

“The fact is that as you set the goals for going zero carbon, as the electricity gets cleaner, the grid gets cleaner and cleaner,” he said. “The trend is that your all-electric home is going to have far less emissions. It’s not about today, but if you look at 2030, the generation that’s in 2030, that all-electric home that you build today is going to be a lot cleaner.”

Which Will be Cheaper, Cleaner?

In New Jersey, the latest state to consider a pre-emptive prohibition on bans on natural gas hookups, gas advocates are also pointing to the future potential for low-carbon fuels as a reason to maintain gas pipelines.

At a recent hearing in the New Jersey Senate, Robert Pohlman, managing director of innovation and strategic initiatives at New Jersey Natural Gas, said that ratepayers had invested $17 billion to create the infrastructure through which natural gas is supplied to their homes. That infrastructure could be used to bring alternative fuels, such as hydrogen or renewable natural gas, to consumers, but it would be discarded if buildings transitioned to electricity. (See NJ Legislators Back Alternatives to Electric Heat.)

“The state must not close itself off from the future benefits of investment, innovation and competition happening around low-carbon fuels today,” Pohlman said.

But whether natural gas or electricity is cleaner and cheaper for North Carolina consumers will depend, again, on the local generation mix and rates. EIA ranks North Carolina in the top 10 for overall electricity consumption and the top five for residential electricity sales.

Duke Energy, the state’s largest utility, has committed to cutting its carbon emissions by 50% by 2030 and achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. However, the utility’s integrated resource plan, still pending before the North Carolina Utilities Commission, anticipates adding thousands of megawatts of natural gas generation through 2035.

The utility’s rates will also likely increase in coming years. Under HB 951, Duke will be able to file multiyear rate plans, under which it will only have to file a full rate case once every three years, rather than yearly as it does now. It will be able to raise rates up to 4% per year in between without the approval of the NCUC.