The American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE) on Wednesday released its sixth City Clean Energy Scorecard, with San Francisco for the first time claiming the top spot, followed by Seattle, Washington, D.C., Minneapolis, and Boston and New York tied for fifth place.

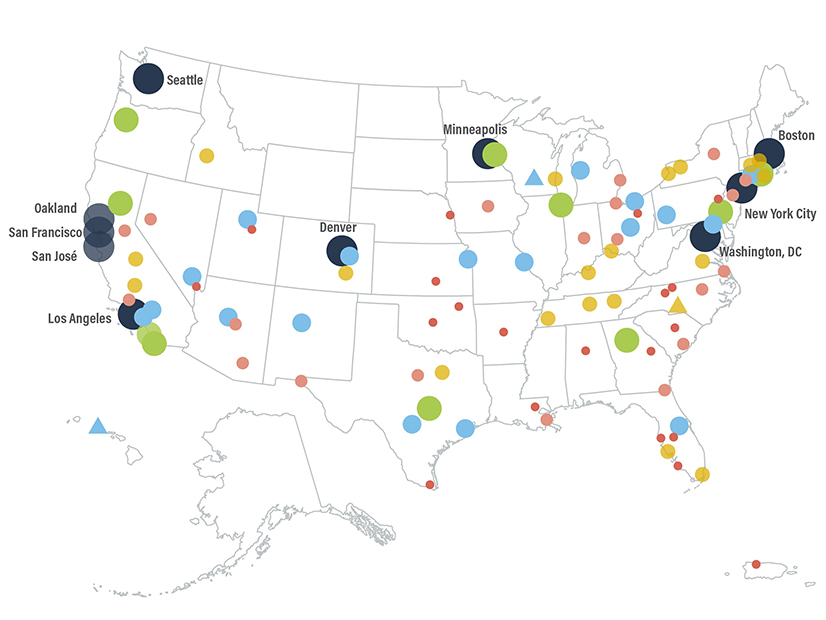

Covering municipal clean energy policies from May 2, 2020 to July 1, 2021, the scorecard ranks 100 U.S. cities across 39 states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. Based on a 100-point scale, ACEEE rates the cities on five key areas of clean energy policy and performance: community-wide initiatives (such as clean energy or emission reduction targets), building policies, transportation policies, efficiency and emission reduction programs of local energy and water utilities and of municipal operations.

The COVID-19 pandemic led many cities to delay or modify planned 2020 work, but cities increased their clean energy efforts in late 2020 and early 2021. | ACEEE

The COVID-19 pandemic led many cities to delay or modify planned 2020 work, but cities increased their clean energy efforts in late 2020 and early 2021. | ACEEETop-scoring San Francisco received 74 points (up 1.5 points from 2020), while at the bottom of the list, Baton Rouge had a total of only 3.5 points (down 2.5 points from 2020). However, ACEEE reported that it had revised some of its scoring criteria to reflect current energy policies and give added weight to equity policies and performance. As a result, 65 cities scored lower than in 2020, the report says.

The report underlines the significant impact city policies and programs can have on climate change. Citing figures from the International Energy Agency, the report says, “Cities around the globe are responsible for nearly three-quarters of the world’s energy consumption and more than 70% of energy-related carbon dioxide emissions.”

The COVID-19 pandemic put a damper on clean energy programs in many cities through 2020, caused by funding, staffing and operational challenges, the report said. However, the first half of 2021 saw renewed momentum on clean energy, with a particular focus on the buildings sector.

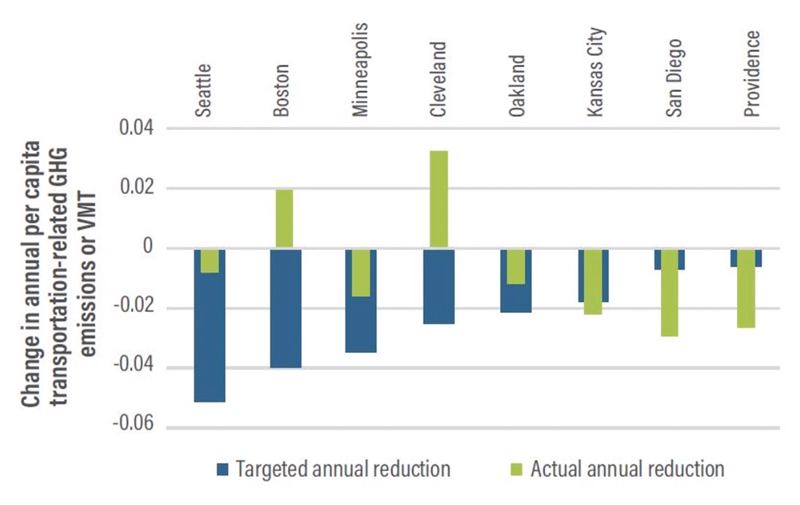

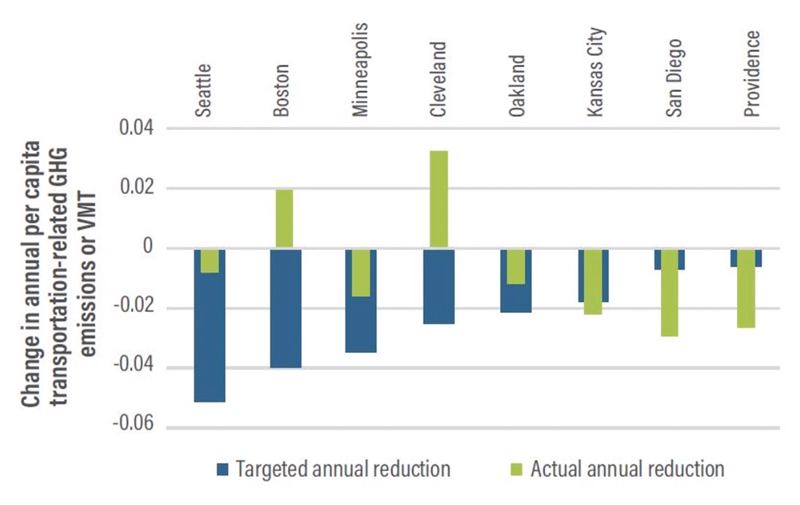

While many cities have set targets for reducing GHG emissions from transportation, only eight are tracking data on emission reductions and of those, only three — Kansas City, San Diego and Providence — are meeting their goals. | ACEEE

While many cities have set targets for reducing GHG emissions from transportation, only eight are tracking data on emission reductions and of those, only three — Kansas City, San Diego and Providence — are meeting their goals. | ACEEE“A lot of the activities were the creation of new incentive programs to encourage retrofits of homes and businesses,” said Stefen Samarripas, local policy manager for ACEEE, speaking at a Wednesday webinar launching the report. “There’s a lot of room to make further improvements in building energy efficiency by creating requirements that property owners make improvements to those properties.”

Data collection is another area for improvement, Samarripas said. Many cities “are not tracking consistently the data that would be needed to figure out if they’re on track to achieve [emission reduction goals],” he said, which is “particularly notable when it comes to transportation-specific goals.”

Only about one-quarter of the cities on the list have set emission-reduction goals for transportation, Samarripas said. Of those, only eight are tracking their data, and of those eight, only three — Kansas City, San Diego and Providence — are hitting their targets, he said.

The Total Buy-in Equation

The webinar also featured energy managers from three cities — San Francisco, Madison and Washington, D.C.

Debbie Raphael, director of San Francisco’s Department of the Environment, said her city has reduced its greenhouse gas emissions 41% since 1990, while its population has grown 22% and GDP 200%. The secret behind those numbers, she said is a “total buy-in equation.”

“It starts with the leadership of our mayor, our elected officials,” Raphael said. “We have business and educational institutions that are bought in — our community organizers, our residents and our voters. … So, this package of buy-in, this package of willingness to take risks and take bold action to prevent harm is what leads to those kinds of numbers.”

Raphael also noted that San Francisco had also recently released an updated climate action plan that is science-based, includes metrics and accountability, and is “centered on people, not just carbon,” she said. “It looks at the power unique within cities and that is land use, the power of land use to affect our greenhouse gas emission reductions. Our mayor [London Breed] loves to say, ‘Housing policy is climate policy.’”

Her advice to other cities is to approach climate and clean energy policy with “radical curiosity.”

“We’re going to have to challenge our assumptions about people’s behavior, about what people need, about what services are possible, what incentives are necessary,” Raphael said. “We really need to ask, with an open mind, what are the programs that will move the needle?”

The First Electric Fire Engine

Wisconsin’s capital is one of the most improved cities in ACEEE’s 2021 rankings, going from No. 64 in 2020 to No. 39 this year. At least part of that leap can be traced to the city’s progress toward running municipal operations 100% on clean energy by 2030. Madison is almost at 75%, said Jessica Price, the city’s sustainability and resilience manager, and “reaching this goal has really required us to take an innovative and multifaceted approach,” she said.

Madison has installed 1.3 MW of behind-the-meter solar at its city facilities, Price said, and the majority of those installations were completed through the city’s GreenPower workforce training program that prepares young people for jobs in renewable energy.

On the transportation side, she said, the city now has 60 electric vehicles and 100 hybrid EVs, and in June, it unveiled the nation’s first electric fire engine. Madison this year passed an ordinance requiring EV charging infrastructure in parking facilities.

Price also emphasized the need for regional collaboration, especially for mid-sized cities such as Madison. “Partnering with our local government neighbors can be a really powerful strategy for scaling up our work, creating regional change, sharing success stories, sharing failures and leveraging our resources,” she said. “Oftentimes we’re operating with limited budgets, limited resources, and the ability to collaborate with folks on shared priorities can be a great way to move things forward.”

Operationalizing Equity

Maribeth DeLorenzo, sustainability director for the nation’s capital, said ACEEE’s increased focus on equity reflected work now underway in her city. “Both at the mayoral level and on the council level, we have new offices of racial equity,” she said. “We’ve been working on racial equity impact assessments that are city-wide, so really moving from understanding how important racial equity is … to how do we operationalize that and what does it look like for us in D.C.”

One way, DeLorenzo said, is the city’s focus on affordable housing and the development of an affordable housing retrofit accelerator. The program helps affordable housing owners understand the city’s building energy performance standards and how to leverage opportunities for building efficiency, according to D.C.’s Sustainable Energy Utility.

D.C. also faces a complicated challenge in cutting its transportation emissions, a significant part of which are caused by commuters driving into the city from the Maryland and Virginia suburbs. To get people out of their cars, DeLorenzo said the city had rolled out three new car-free lanes for buses and bikes along key commuter routes, while also working on electrifying its own municipal fleet.

Echoing Raphael, she also emphasized the importance of buy-in. “In some places, it means focusing on adaptation. In some places, it means lining up partners who may have disparate interests with the same aim at the end,” she said. “And then in other places, it really means taking a hard look at our climate action through the lens of who has the ability to [have an] impact.

Room for Improvement

Funding in the bipartisan infrastructure bill — and in the Build Back Better Act, now stalled in the Senate — has cities excited and looking at how they will plug into the federal dollars.

One challenge, Raphael said, is that the money will come through the state in the form of grants or other funding opportunities before it gets to the cities. “How do we help cities communicate up to the state [and] states to the feds so that we at the implementation side, whether it’s affordable housing or transportation, get the money we need in the right ways that we need it so that we serve our communities?” she said.

The report also has recommendations for program development — with or without federal funds — stating that even the scorecard’s top-ranking cites have room for improvement. Key suggestions include:

- A range of social equity policies, such as creating a formal clean energy decision-making body of historically marginalized community residents and helping minority-owned and women-owned businesses to secure local government clean energy contracts.

- Mandatory policies designed to improve the energy performance of existing buildings, such as energy benchmarking and performance standards and policies to promote energy efficiency retrofits.

- Higher targets for community-wide and transportation-specific clean energy goals. As noted, setting transportation goals and metrics are a major lapse in local clean energy policies.

“We know the actions that need to happen, on the building sector, on the transportation sector, on the social and environmental justice sector,” Raphael said. “It’s really a question of political will. And that political will gets built from a foundation of government power and expertise and support by our private sector and by our residents. That’s what we need. We need us all to lean in.”