The Biden administration’s $9.5 billion bet on hydrogen becoming an industrial and transportation fuel in the future may come down to how easily the colorless and odorless gas can be transported.

Mitsubishi has been working on that problem for years and believes it now has a solution: store the gas in a “carrier,” a common industrial organic compound such as methylcyclohexane (MCH). A liquid at ambient temperatures, MCH can be handled like gasoline and moved around the world in tankers and pipelines.

Working in a consortium with other Japanese companies, Mitsubishi proved the concept in 2020 with a project in which green hydrogen was repeatedly produced in Brunei, a small sun-drenched country on the island of Borneo and shipped to Japan in ordinary tankers.

Kiichiro Fujimoto, general manager of Mitsubishi’s Infrastructure Solutions Department, explained the process and Japan’s goals to cut carbon emissions in half by 2030 during a webinar produced Thursday by the D.C.-based Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Fujimoto explained that the hydrogen was mixed with toluene, a common solvent and degreaser, creating the liquid MCH.

“MCH is very chemically stable, [exhibits] a very minor loss during the long-term storage and long-distance transportation. It’s easy to handle,” he said. When the hydrogen was recovered from the MCH in Japan, the solvent was shipped by tanker back to Brunei.

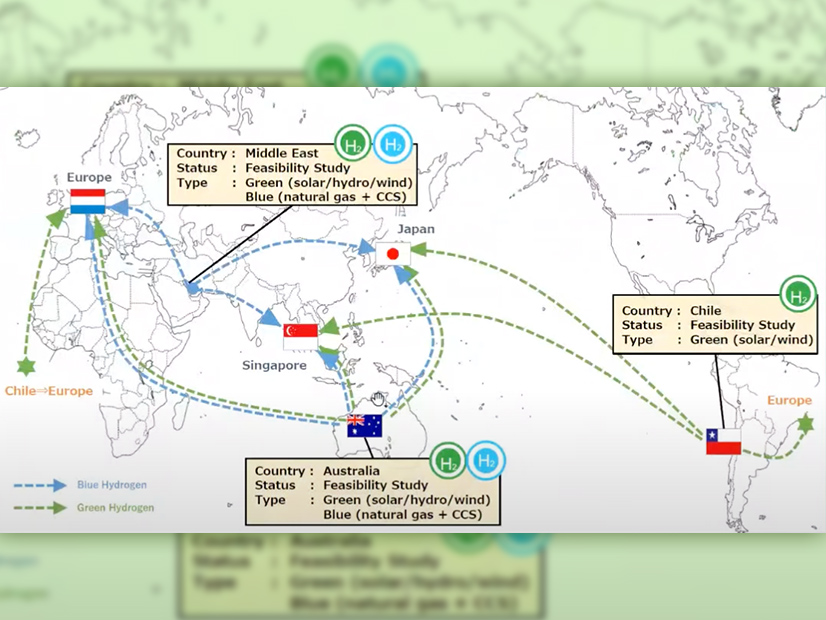

Mitsubishi and its partner companies in the Brunei project believe that the MCH method can be used to ship hydrogen from Australia and Chile, two countries that are planning to make hydrogen with renewable power. (See Global Hydrogen Conference Reveals Plans to Ship Sunshine.) Middle Eastern companies are also planning to produce green hydrogen, which could be shipped to Europe as well as Japan.

Scale — both in production and in use — is the key to making hydrogen affordable, Fujimoto said.

“Here is the important part: In order to support this billion-[dollar]-size project, we need a very reliable hydrogen producer, a very reliable hydrogen buyer, and we need a very reliable hydrogen carrier technology and a company that operates all these operations,” he said, adding that his company is working on business opportunities in Singapore and Europe.

Snam, an Italian energy infrastructure company, is working to create a hydrogen supply chain not only in Italy but across Europe to move the hydrogen once it arrives from overseas.

Giovanna Pozzi, in charge of renewables and power supply for hydrogen at Snam, said the company has been blending hydrogen with natural gas in ongoing tests of its pipelines.

In a controlled test, she said the company delivered gas containing 10% hydrogen to a glass maker and a bakery. Neither business had any problems, nor did the pipelines, she said.

“We have been able to define the new technical standards for the injection of hydrogen into our pipes. We’re moving to different countries into Europe because we are teaming up with the 23” other companies, she said. “We are exchanging information with a very ambitious aim: the creation of the first European hydrogen backbone.”

The hydrogen-dedicated network would be about 40,000 km, she said, of which 70% would be repurposed existing gas lines and 30% new construction. (See Roundtable Looks at Storage, Hydrogen to Decarbonize Northeast.)

But to make this work, the 23 companies need new common, European-wide policies and regulations, which currently do not exist, she said.

“I think that the key success factors that we are talking about are technical constraints and standards, new standards for these gases. And then the regulation and funding support,” she said.

Neil Navin, vice president for clean energy innovations at Southern California Gas (NYSE:SRE), said his company has also worked on blending and sees aggregating demand for hydrogen as important to moving to large-scale production and use.

Pointing out that California has a significant industrial base that could use hydrogen in place of hydrocarbons.

“The key to electrolytic [green] hydrogen is to put the solar panels in the place where the sun is most intense, and most often … making sure that you can situate your renewables in those locations, co-produce hydrogen and then transport that hydrogen into the demand centers,” he said. “That really dictates the topology of transportation.” (See related story, SoCalGas Proposes Hydrogen Pipelines.)

Navin added that the hub concept advocated by the Biden administration — producing a lot of hydrogen in an area abundant in renewables or natural gas — just makes sense financially.

“We found that there is a real logic to looking for the areas of highest renewable penetration for the source of hydrogen,” he said, rather than producing it locally.

“It seems counterintuitive, but once you look at the math, the economics become more apparent. So, what I think you’ll find in each region, especially in the United States, is that demand will likely not move, [and] the factory will stay where it is.

“The power plant will stay where it is. People will not move to the renewables; you will have to move the hydrogen to them.”