While the Biden administration has touted the infrastructure bill approved last year as a way to address climate change, state and local discretion over highway spending could actually cause increased emissions, an analyst told the Maryland Greenhouse Gas Mitigation Working Group Tuesday.

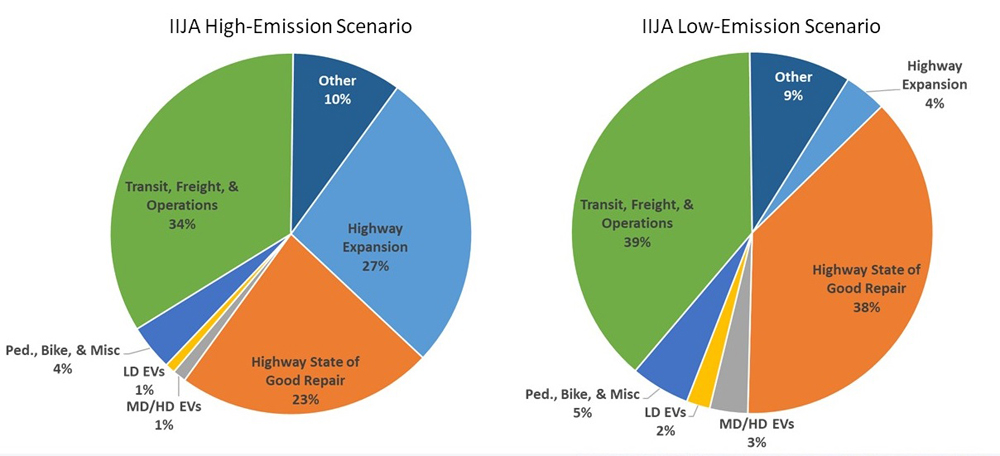

James Bradbury, mitigation program director for the Georgetown Climate Center, told the working group that the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act will provide about $599 billion in funding for surface transportation for 2022-26, giving state and local governments discretion to spend as much as 27% of it — or as little as 4% — on new highway construction.

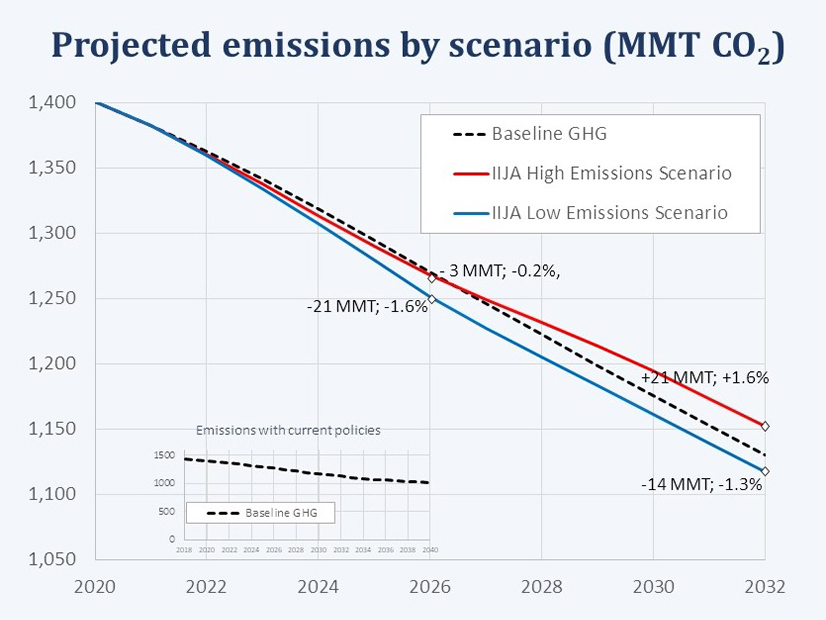

According to the Climate Center’s analysis, spending on new highways could increase emissions beginning in 2026, resulting in a 1.6% increase relative to the baseline by 2032.

“That’s because building more roads consistently results in more traffic — an ‘if you build it, they will come’ effect known as ‘induced demand,’” the center said. “In short, traffic expands to fill the new lanes within a few short years, bringing with it more pollution.”

In contrast, limiting new highway spending to 4% of the total would reduce emissions by 1.3% from the baseline.

“This may not sound like much, but it’s substantial for nationwide transportation emissions in just five years,” Bradbury said.

Between 2010 and 2020, an average of 15% of obligated federal funds administered by the Federal Highway Administration was used for highway expansion projects, including new construction, relocation, reconstruction (added capacity), new bridges and major bridge rehabilitation.

“We think the real-world outcome will end up somewhere in between” the high-emission and low-emission scenario, Bradbury said. “Certainly it’s too soon to say where things are headed; It’s a five-year spending bill. But projects are already being funded.”

Although formula funding programs have long provided flexibility for highway dollars to be used for emission-reducing investments like transit and electric vehicle charging, it’s not required by law.

“So those decisions are really largely left up to the states to make,” Bradbury said. “To ensure that investments result in meaningful [emission] reductions, concerted efforts are going to be needed across all levels of government, the state [departments of transportation] will obviously play a crucial leadership role, but governors, legislators, local governments, municipal planning organizations will also be a part of these decisions,” he added.

Telecommuting ‘A Wash’ on Emissions

Bradbury said the increase in telecommuting because of the pandemic has not had a significant impact on emissions because of “rebound effects.”

“While you have some people working from home, oftentimes, those people … might hop in their car at lunchtime and drive to the mall and do some shopping, and the net effect are they tend to have more trips near home,” he said. “You know, those commutes to work oftentimes would be multi-purpose: They pick up kids on the way home and stuff at the grocery store on the way home, as opposed to doing lots of local individual trips. … The net effect of telecommuting, working from home, on VMT [vehicle miles traveled] tends to be somewhat of a wash.”

Angst over EV Costs

Michael Powell, co-chair of the working group, questioned whether funding supporting EV charging would be better spent on subsidizing the vehicles.

“I just spent a lot of time in meetings with building owners and developers who are complaining that they’re putting in electric charging stations and nobody plugs in there,” he said. “I’m beginning to believe that it’s not an infrastructure issue in the short term: it’s the cost of the cars. … I’m beginning to think that we’re getting the cart before the horse here — that if we could lower the cost of the vehicles, people would solve a lot of the charging problems by putting just level one chargers in homes and workstations.”