As laid out in a report released Tuesday, Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s (R) main argument against Virginia’s participation in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) appears to be that none of the $300 million the state has received to date from the 11-state cap-and-trade program is being used to provide rebates to customers.

Because the state’s main utility, Dominion Energy, is allowed to recover the cost of the carbon allowances it must buy to comply with the program from its “captive” customers, Virginia’s participation in RGGI has resulted in a “direct carbon tax” on residents and businesses, the report says.

Announcing the report, Youngkin reiterated his longstanding claim that RGGI is “a bad deal for Virginians,” invoking the added burdens that recent inflation is putting on residents “at the pump and at home.”

According to the report, Dominion’s recovery of its RGGI costs has added $2.39/month to residential utility bills and $1,554 to bills for industrial customers. According to figures supplied by Dominion to the State Corporation Commission, cited in the report, the utility expects that RGGI participation will cost customers a total of $3 billion through 2045.

These increases are framed as an “emergency situation” allowing the governor to issue an emergency regulation to take Virginia out of RGGI, according to a draft letter from Michael Rolband, director of the state’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ). The letter and a copy of the proposed regulation repeal accompanied the report.

Under Virginia law, an emergency regulation of this kind could stay in force for up to two years. A draft of a letter notifying RGGI of Virginia’s intent to withdraw is also included with the report.

Environmental and clean energy advocates were quick to criticize the report’s arguments and Youngkin’s plans for RGGI withdrawal.

“The report willfully ignores the massive benefits that come from our participation in RGGI,” said Chelsea Harnish, executive director of the Virginia Energy Efficiency Council, noting that half of the state’s RGGI funds go to energy efficiency projects for low-income residents. Another 45% goes to flood preparedness programs, with 5% allocated to cover administration costs.

Nate Benforado, a senior attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center, slammed the report as “designed to support a partisan repeal effort rather than to provide an objective look at available information.”

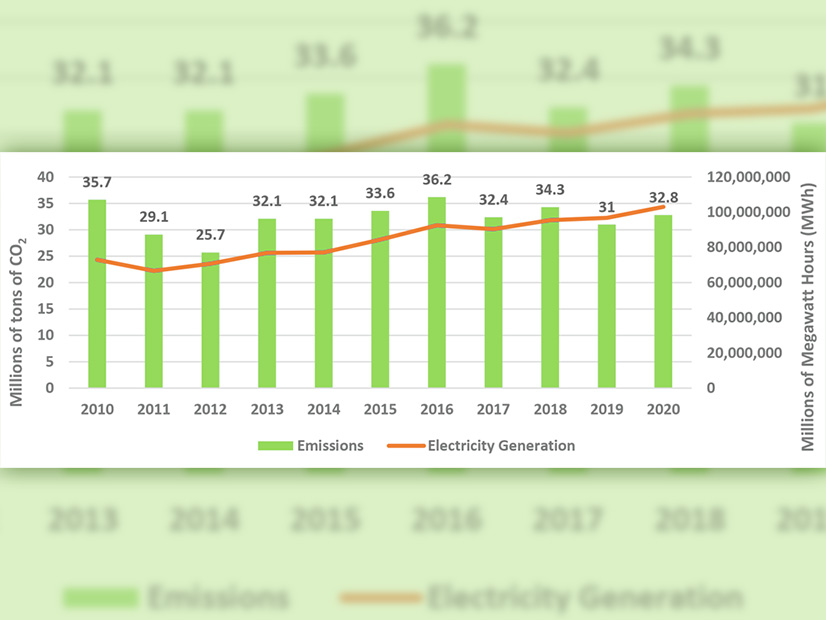

The report actually finds that “RGGI is working very well,” Benforado said in an interview with NetZero Insider. While RGGI states have cut GHG emissions more than 30% over the past decade, the report shows that Virginia’s emissions have remained about the same, he said.

‘A Pretty Misleading Statistic’

Youngkin’s report counters that while Virginia’s emissions have not declined overall, the state’s “emission rate, which is the amount of CO2 emissions produced by a set amount of electricity, has steadily and significantly been reduced.”

But Benforado said such emission rates are “a pretty misleading statistic to look at” and can be attributed to the retirement of coal plants in the state and the increasing use of natural gas to generate electricity.

“When it comes to climate change, emissions rate doesn’t matter at all,” he said. “It’s all about the actual amount of CO2 you’re putting into the air. … Virginia has fallen behind the other RGGI states.”

Further, the report also acknowledges that without an emissions-reduction program like RGGI, Virginia will not be able to meet the clean energy goals of the state’s Clean Economy Act, which requires Dominion to decarbonize its system by 2045, Benforado said.

“It seems like the issue the governor really has is less about RGGI and more about the cost to customers,” Benforado said. “If the governor is sincere that that’s his concern, then we should address that; repealing RGGI doesn’t fix that problem.”

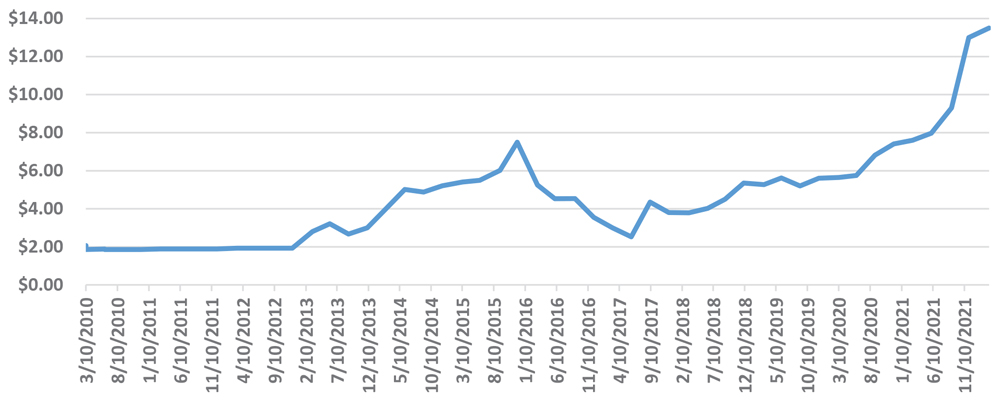

RGGI was founded in 2009 as a regional “cap-and-invest” program, according to its website. Participating states set annually decreasing caps on carbon emissions from power plants, which must then buy allowances issued by the states to offset their emissions. One allowance offsets 1 ton of carbon dioxide. States can invest their RGGI funds in clean energy, energy efficiency or GHG abatement programs or in rebates and bill credits to customers.

As noted in the report, four states in RGGI — Delaware, Maryland, Maine and New Hampshire — do use a portion of the money they receive from RGGI’s quarterly auctions to provide rebates to customers to offset any increase in rates that comes from the program. Virginia’s program was originally designed to include customer rebates, the report says, but was later changed to split the money between low-income energy efficiency and flood preparedness programs.

J.R. Tolbert, vice president of strategy and partnerships for Advanced Energy Economy (AEE), defended the legislature’s decision to split Virginia’s RGGI funds as it did. According to Youngkin’s report, to date, the flood preparedness program has received more than $150 million in funding, while low-income energy efficiency programs have received more than $135 million.

“The governor seems to have picked a boogeyman in RGGI versus actually providing solutions on big issues, whether it be a rebate [or] how he would replace the money that’s going to communities all over the commonwealth dealing with rising water levels and how he would help low-income Virginians address energy efficiency needs in their homes,” Tolbert said.

‘The Courts Will Rule’

Advocates and Virginia Democrats have also argued that Virginia joined RGGI as the result of a 2020 legislative mandate (SB 1027), and therefore Youngkin does not have the unilateral authority to take the state out of the initiative.

“The legislature codified Virginia’s participation in RGGI, and in order for the state to withdraw from RGGI, the legislature would have to make that decision,” Tolbert said.

While Tolbert said AEE is not planning to take the governor to court, he expects that others will. “I think the way this plays out is that the courts will rule that we continue to stay in RGGI until the legislature decides otherwise,” he said.

However, an analysis from industry analysts ClearView Energy Partners suggests that the law may not codify RGGI, creating a fine point for the courts to decide. The language in the 2020 law “authorizes” the DEQ to design and implement Virginia’s RGGI program, ClearView said. Such language could be read as giving the DEQ permission for a RGGI program but not necessarily a mandate.

Tolbert, who advocated for the bill at the time, disputes that interpretation. “The legislative intent was that this was a mandate,” he said. “The reason they passed the law in the first place was because they wanted to take that extra step.”

Air Pollution Control Board

After his victory over Democrat Terry McAuliffe in the November election, Youngkin came into office vowing to take Virginia out of RGGI and signed an executive order to begin the process just hours after his Jan. 15 inauguration. (See Youngkin Takes 1st Steps Toward Va. RGGI Withdrawal.)

The order directed the Department of Natural Resources and DEQ to conduct a new cost-benefit study of Virginia’s RGGI participation and draft the letters and emergency regulations that would allow Youngkin to circumvent the legislature in taking the state out of the initiative.

With a Democratic majority in the state Senate opposing any effort to repeal the RGGI mandate, Youngkin’s strategy depends on the State Air Pollution Control Board. At the time of his inauguration, the board had a solid majority of members who had been appointed by former Gov. Ralph Northam (D). It had approved the regulations setting up Virginia’s participation in RGGI by a 5-2 vote and appeared unlikely to reverse that decision.

In the interim, however, the Senate rejected Andrew Wheeler, the former EPA chief under President Donald Trump, as Youngkin’s secretary of natural and historic resources. Wheeler, along with Rolband, was responsible for leading the RGGI withdrawal efforts. Youngkin has since made Wheeler a senior adviser, a post that does not need confirmation. (See Va. Senate Committee Rejects Wheeler Nomination.)

At the same time, the General Assembly rejected two members of the Air Pollution Control Board — Joshua Behr and Richard Langford — who had been nominated by Northam but not yet confirmed, leaving two vacant seats, according to DEQ spokesperson Anissa Rafeh. Two other members, Vice Chair Kajal Kapur and Gail Moore, term out in June.