Drafted to help achieve an ambitious goal of nearly quadrupling New Jersey’s solar output over the next decade, new rules proposed by the state Board of Public Utilities (BPU) to govern what land can be used for projects received a moderate reception last week, with little outright opposition but a stream of queries and suggested improvements.

More than a dozen speakers — among them solar developers, environmentalists and farming advocates — raised a host of thorny issues, among them how the rules would work in practice, what protections for soil are in place and how flexible the guidelines would be when enforced. Key among the issues raised by developers were concerns that the cost of compliance would be so great that projects would become unviable.

“I do think that job No. 1 should be to make sure that we can accomplish these purposes at the lowest possible cost,” said Fred DeSanti, executive director of the New Jersey Solar Energy Coalition.

Matthew Tripoli, director of project development at CS Energy, said the company supported statewide standards that would apply to all projects.

“It’s a great idea to have having the rules be extremely clear, as it looks like [that’s what] the attempt is here with these guidelines,” he said. “We’re just a little concerned that the guidelines as proposed don’t really seem to provide much flexibility and seem to value [agriculture] impacts over and above all others.”

Ethan Winter — Northeast solar specialist for the American Farmland Trust, which works to protect farmland and promote environmentally sound farming practices — said the BPU should place greater scrutiny on what soil would be affected by proposed projects and how to reduce the impact.

“We would encourage New Jersey to set a high standard in terms of minimizing and avoiding soil disturbance in the first place,” he said.

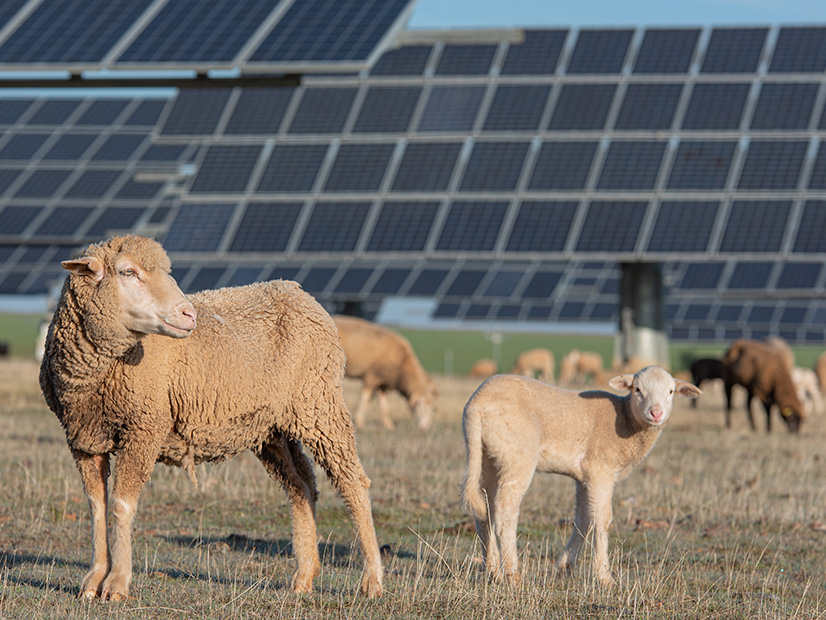

The release of the guidelines follows growing concerns in New Jersey, as in other states nationwide, over the impact of rising demand for space on which to site solar projects on farmland. Aggressive demand for land, and related high-priced lease and purchase offers from developers, has forced farmers to decide whether to accept the income from solar opportunities or reject it to protect their farms and way of life. (See NJ Solar Push Squeezes Farms.)

A similar dynamic has played out in Ohio, where solar supporters see a 350-MW project on 1,880 acres of prime farmland bringing much needed revenue for schools. In San Diego, local officials see solar developments as key to cutting carbon emissions and eye farmland as the place to put them.

In New Jersey, there is an additional dynamic: The pressure to develop farmland has been elevated by an explosion in the demand for warehouse space from e-commerce and logistics companies that serve the Port of New York and New Jersey and the massive New York-area population.

Evaluating Solar Sites

The hearing was the second into the siting proposals, which were drafted as part of the state’s new Competitive Solar Incentive (CSI) program.

The program governs utility-scale projects and net-metered commercial installations larger than 5 MW. It is part of the state’s Successor Solar Incentive (SuSi), which the BPU approved in July as part of a reshaping of the state incentive programs designed to reduce the cost of projects while stimulating the development of certain types.

New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy wants the state to reach 100% clean energy by 2050, with solar a key part of the equation. The state’s official Energy Master Plan calls for deploying increasing amounts of solar: 5.2 GW by 2025; 12.2 GW by 2030; and 17.2 GW by 2035. Yet the state’s new installation capacity in recent years has been well below what would be needed to reach those goals.

The location guidelines under the CSI program divide potential solar sites into four categories, each of which treats the projects differently. One category covers land on which any development is prohibited, which includes preserved farmland and areas that contain prime agricultural soil. A second category — such as wetlands or forest land protected by the state — allows construction only if the BPU approves a waiver. A third category allows the siting of a solar project subject to a cap that limits how much of that land can be developed for solar capacity statewide. And the fourth category is land for which there are no restrictions on what solar developments can be undertaken.

The rules also set out guidelines designed to mitigate the impact on the land of an approved project as it advances to completion. The rules include a requirement that the developer hire an environmental monitor, take stormwater management measures and implement soil stabilization measures.

The aim of the rules is to “minimize as much practical and potential environmental impacts, and include consideration of existing and prior uses of the property, any conservation or agricultural designations associated with the property and the amount of soil disturbance,” Steven Bruder, planning manager for the State Agricultural Development Committee, told the hearing. “The soil protection guidelines are intended to apply whenever the intention is to return lands to agricultural use [at] the end of the life of the solar installation project.”

That scrutiny will include a “six-year-monitoring period” that will include an evaluation of the site every other year, said Frank Minch, director of the Department of Agriculture’s Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources.

Protecting Soil

The close evaluation of the site made sense to Amy Hansen, policy manager at the New Jersey Conservation Foundation, who said she also owns and operates and organic fruit and vegetable farm. She urged the state to ensure that the project inspector has a good knowledge of “soil health.”

“I think it’s important to not be under the impression that topsoil will ever return to its original condition once it’s been removed and moved,” she said. “Removal of topsoil will negatively impact the soil structure and chemistry, as soils form over thousands of years. It’s a delicate balance. So, I think protecting soils, especially prime and soils of statewide importance, really needs to be a strong requirement.”

That kind of close attention to the soil, however, raises concerns for Scott Elias, director of Mid-Atlantic state affairs for the Solar Energy Industries Association, who said that parts of the industry already embrace some of the BPU’s proposals, such as hiring an environmental monitor. He said a “workable siting process is imperative” if the state is to create enough new capacity to meet its goal of 1,500 MW of large-scale solar facilities by 2026, and suggested that some of the guidelines go too far.

For example, a BPU requirement that the developer conduct a soil compaction test every 250 feet before and after construction could be “unduly burdensome and impractical for larger facilities,” he said. And a requirement that land be seeded and mulched within “seven days of disturbance” is impractical; the time period should be extended to 90 days, he said.

“We really do think this is moving in an OK direction,” he said. “But we do think we need to further balance the need for permitting more solar projects with protecting property rights and sensitive ecosystems.”