A comprehensive economic study prepared by Cleveland State University concludes that diverting just 15% of Ohio’s current Utica shale gas production to create hydrogen would be sufficient to satisfy existing demand, mostly by the state’s petrochemical, fertilizer, steelmaking and refining industries.

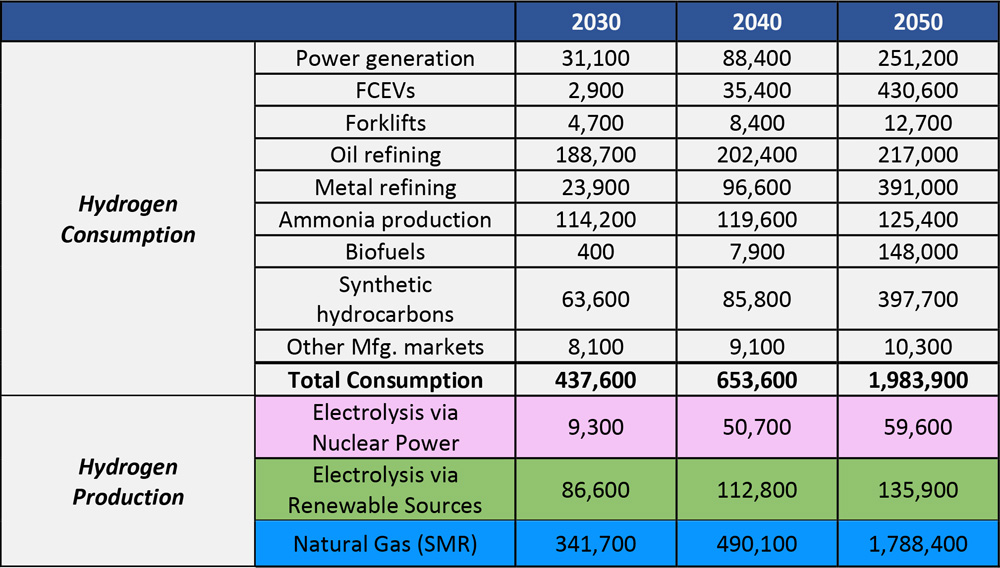

But anticipated growth in demand for use in new technologies — such as blending with natural gas to fuel turbines generating electricity; replacing coke as a reducer in steel production; and fueling fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) — along with traditional industrial use could outpace production of hydrogen from natural gas by 2050 when Utica shale gas production is projected to decline, the 76-page analysis concludes.

The study starts with the assumption that Ohio has an advantage over other states now competing for $9.5 billion in federal funding underpinning the Biden administration’s goal to foster the creation of regional “hydrogen hubs” that would use locally produced hydrogen.

“Ohio has several key advantages over other states in ramping up a hydrogen economy, beginning with its already significant industrial hydrogen market, led by the steel, petrochemical and fertilizer industries,” the analysis begins.

“In the coming years, Ohio will see these industrial markets grow and can leverage them to capture developing power generation, transportation and chemical hydrogen markets. This will be so because Ohio is also in a position to cost- effectively generate, store and deliver large volumes of hydrogen to supply these markets” the report reasons in a reference to the state’s enormous shale gas production. “This includes finding markets for carbon dioxide captured from hydrogen generation” from natural gas.

The state’s industries already produce 161,000 metric tons of hydrogen annually with steam methane reforming (SMR), according to the report, and it could probably meet all the anticipated demand. But relying solely on an increase in production through SMR would create more carbon dioxide that would have to be either sold to other industries as needed or more likely pushed into deep injection wells, adding another cost, according to the report.

The analysis assumes that a carbon tax will not be immediately enacted. While natural gas prices are expected to remain relatively low in the coming decades, other issues — the adoption of FCEVs in trucking, the use of hydrogen in steelmaking, and the cost of building a hydrogen storage and pipeline system — mean that developing an exact timeline is difficult to predict, the analysis warns.

“We know that near-term hydrogen will likely be supplied principally by natural gas via SMR. We also know that hydrogen infrastructure like SMR plants and pipelines have a useful lifespan of up to 50 years, and once built, those assets will not readily be discarded.

“Accordingly, Ohio is likely to be dominated by natural gas-based hydrogen for some time. Indeed, natural gas assets already exist in Ohio that could catalyze a hydrogen economy over the next 10 years, thus enabling Ohio to be a leader in hydrogen development. These assets also include an existing industrial hydrogen market supplied by natural gas.

“We also know that there will likely be a transition at least in part from natural gas to carbon-free forms of hydrogen, like those coming from electrolysis using nuclear and renewable power. How soon these are developed, and what fraction of the hydrogen they can supply, may depend upon regulation of carbon dioxide emissions.

A comprehensive economic assessment of efforts in Ohio to decarbonize heavy industry concludes that diverting 15% of the state’s shale gas output to hydrogen production could meet existing industrial demand but to meet anticipated demand growth by 2050, 15% of renewable generation and Ohio’s existing nuclear power will be needed. | Midwest Hydrogen Center of Excellence, at Cleveland State University

A comprehensive economic assessment of efforts in Ohio to decarbonize heavy industry concludes that diverting 15% of the state’s shale gas output to hydrogen production could meet existing industrial demand but to meet anticipated demand growth by 2050, 15% of renewable generation and Ohio’s existing nuclear power will be needed. | Midwest Hydrogen Center of Excellence, at Cleveland State University

“Even without regulation, however, we can project that they will likely provide an increasing share of hydrogen production and by 2050 may even approach that provided by natural gas,” the report reasons.

Also by 2050, the study assumes that transportation, led by heavy trucking, will be the largest consumer of hydrogen in the state, while cars and light-duty trucking will have moved to battery EVs.

“We also project that heavy-duty trucks (Class 8) will be a major early consumer of hydrogen in the region, where refueling infrastructure can be built along interstate corridors. The Pittsburgh-to-Chicago I-76/I-80 corridor, for instance, is projected to use around 1,200 kg/day by 2030 and about 20,000 kg/day by 2040, even without zero-emission mandates,” the study notes.

Going Green

Working under the assumption that shale gas production will be in decline by 2050, the study turns to green hydrogen, which is produced by electrolysis using not only electricity from wind and solar but also from the state’s two nuclear power plants, Davis-Besse east of Toledo and Perry east of Cleveland.

Energy Harbor, the owner of the two power plants, is working with a $10 million U.S. Department of Energy grant on a facility adjacent to the Davis-Besse plant to use a portion of the reactor’s output to make hydrogen with a low-temperature electrolysis. The project is expected to begin production in 2023.

The study assumes that by 2050, 15% of the energy generated by Energy Harbor will have been diverted from the grid to produce enough hydrogen to meet the expected demand growth. And it assumes that renewable energy projects, primarily solar, will also have to contribute 15% of all energy generated in order to meet hydrogen demand.

“Ohio will likely be looking to supply this larger 3 million metric ton market at the same time that natural gas production from Utica Shale and other Appalachian formations are in decline,” the analysis warns.

“Ohio will need to develop a green hydrogen strategy to prepare for this scenario. Based upon current projections for Ohio generation capacity, if the state repurposed 50% of its nuclear and utility-scale renewable power fleets to make hydrogen for a 2-MMT/year market, it would still be required to support 70% of its hydrogen from steam methane reformation by 2050.

“A 3-MMT/year market will only require more natural gas. Further, 50% repurposing of nuclear and renewable power will put a significant strain on Ohio’s grid, which already imports around 25% of its power.

“Accordingly, Ohio industries will need to plan for both blue and green hydrogen sources to supply Ohio’s anticipated hydrogen demand. It will need to develop strategies for using or sequestering carbon dioxide captured from steam methane reforming processes. And it will need to ramp up its green power generation fleets to replace natural gas over time. This will include extending the life of its nuclear power plants and significantly increasing its fleet of utility-scale renewable power.”

The study was also sponsored by Jobs Ohio, a private economic development group created by the state, and the Stark Area Regional Transit Authority, a regional transit system with 20 fuel cell electric buses. The research was led by Mark Henning and Andrew Thomas of the Energy Policy Center at Cleveland State University’s Levin College of Urban Affairs.