ATLANTIC CITY, N.J. — New Jersey is staking its claims in the offshore wind supply chain, with a monopile factory preparing to start production and the announcement of the first tenant at its offshore Wind Port — both involving large European companies that have been in the industry for decades.

But building a thriving offshore wind industry in the U.S. will require many home-grown members of the supply chain, speakers told the International Offshore Wind Partnering Forum last week.

“If the offshore wind industry is going to survive and thrive, it needs a robust and sustainable and diverse supply chain in the U.S.,” said Amanda Schoen, U.S. policy specialist for Vestas, a Danish turbine manufacturer that has manufacturing facilities in Colorado. “This is where the market is, and there’s a desire to be where the market is. But you do need to grow the industry.”

That needs to happen soon, said Ross Gould, vice president of supply chain development for the Business Network for Offshore Wind, which organized the conference. He told a panel that the U.S. is not ready to meet President Biden’s goal of 30 GW of offshore wind by 2030.

“The U.S. doesn’t have sufficient manufacturing infrastructure,” he said. “Meeting the national offshore wind target would require over 2,000 turbines.” It also will require 11,000 kilometers of cable, five wind turbine installation vessels, 10 feeder barges, eight crew transfer vessels and four cable-laying vessels, Gould said, citing data from a report released in March by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

And the U.S. can’t rely on getting those elements from other, more mature offshore wind markets, he said, because the “global supply chain will be occupied on … other markets and does not have the capacity to supply all the projects that are needed to meet the 30-GW target.”

Building an Industry from Ground Up

New Jersey officials say they are on their way to developing a supply chain that can serve the state and others on the East Coast, and they say that their experience to date can provide a guide on how to develop it for the future.

Speaking on the final day of the conference, Gov. Phil Murphy announced that the New Jersey Economic Development Authority (NJEDA) had signed up the first tenant for the New Jersey Wind Port, which the state says is the first purpose-built wind facility on the East Coast. Ørsted Offshore North America signed a letter of intent to marshal its Ocean Wind 1 project, including staging, assembling and transporting components, at the port.

“There are many more opportunities to come, including ongoing negotiations between offshore developers and major component manufacturers to bring them to New Jersey,” Murphy told the conference. “This is, if you will, New Jersey’s ‘If you build it, they will come’ moment.”

Murphy wants offshore wind to provide 23% of the state’s energy by 2050, and to that end the state plans to award offshore projects totaling 7,500 MW. The New Jersey Board of Public Utilities (BPU) approved the 1,100-MW Ocean Wind 1 project, owned by Ørsted and PSEG, in 2019, and Ørsted’s 1,148-MW Ocean Wind 2 and the 1,510-MW Atlantic Shores project, a joint venture between EDF Renewables North America and Shell New Energies U.S., last June. (See NJ Awards Two Offshore Wind Projects.)

The BPU expects to award projects in three further solicitations, the first of which will be held early next year.

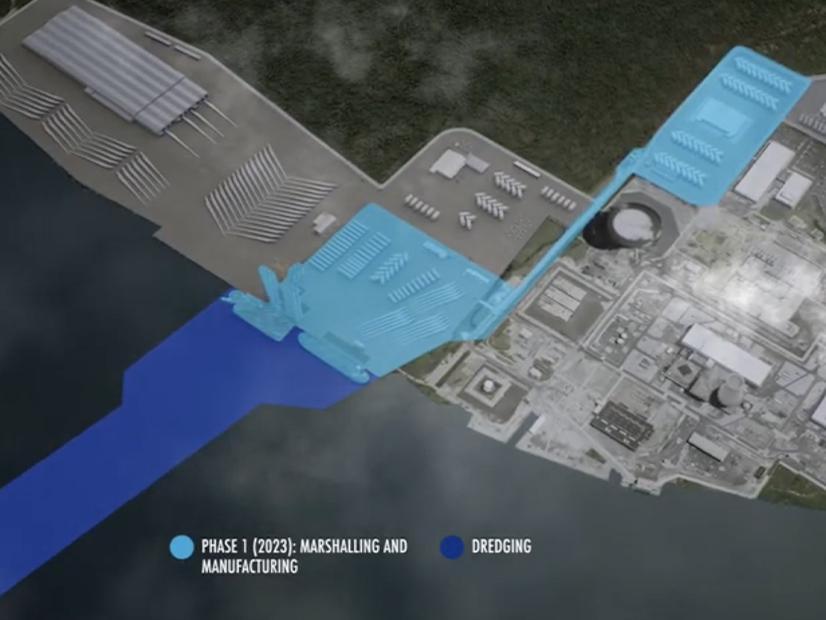

New Jersey officials envision the Wind Port project as a manufacturing and supply chain hub that will serve not only the state’s wind projects but others along the East Coast, noting it is within one day’s ship travel to half of the U.S.’s OSW lease areas. The state has already committed $500 million to the port, which is sited on the Delaware River in Lower Alloways Creek. (See NJ Ramps up Wind Sector Support.)

Expected to open in 2024, the Wind Port will include heavy-lift wharfs and component laydown areas. Subsequent phases are targeted to come online between 2024 and 2026. The project is expected to create up to 1,500 jobs and add $500 million annually to the state’s economy, Murphy said. The EDA says it has seen high demand for space in the port, noting it received 16 non-binding offers in October from companies looking to become tenants. (See NJ Wind Port Draws Offshore Heavy Hitters.)

The Wind Port announcement came as EEW American Offshore Structures said it is close to starting operations at its monopile factory at Paulsboro Marine Terminal, also on the Delaware River, into which the state invested $250 million.

CEO Lee Laurendeau told a conference panel that EEW expected to receive an imported monopile last weekend on which to conduct welding tests.

After that, “our plan is to start working on the Ocean Wind 1 monopiles in November of this year,” Laurendeau said of the factory, which is expected to make 100 monopiles a year.

Case Study

New Jersey’s success to date provided the conference a case study on how the wind sector can overcome the challenges to building a sustainable industry.

New Jersey officials said they had a clear vision early on.

“Right from the start, in 2018, 2019, we really dove in headfirst into offshore wind, conducting a number of feasibility analysis studies, listening sessions with developers and industry visits abroad to really understand how do we bring this industry to New Jersey,” said Julia Kortrey, a senior project officer at the EDA.

“Our theory of the case has really been getting these big first movers, [like] EEW’s monopile fabrication facilities — something that feels tangible and helps really anchor the ecosystem,” to come to New Jersey, said Kortrey. And the state believes that the Wind Port will be attractive to suppliers seeking to locate near the larger companies.

Speaking at the International Offshore Wind Partnering Forum in Atlantic City, Lee Laurendeau, CEO of EEW American Offshore Structure (left), and Julia Kortrey, senior project officer for NJEDA. | © RTO Insider LLC

State officials are now looking at “who are those sub-suppliers? Who are the next tier to further create that ecosystem?” she said.

Laurendeau said EEW looked at multiple states — and at whether a U.S.-based manufacturing operation was feasible — before deciding to build a factory in New Jersey. A key event was a visit in 2018 by Murphy to EEW’s office in Berlin to pitch to the company the idea of building a factory at Paulsboro.

“From a Tier 1 [large] supplier standpoint, the very biggest question you have to answer is, can we build a product cheaper than one coming from Europe,” he said, noting that it costs $1 million to transport a monopile from Europe to the U.S. “That’s, the first business case item that you have to address. And, in Europe, the ports are subsidized. They’re already up and running, they’ve already capitalized their factories, they’re efficient.” That presents an operational challenge and a learning curve to newly created U.S.-based suppliers who are trying to compete, he said.

New Jersey’s investment of $250 million in the project also was key to it moving forward, Laurendeau said. The decision also was made easier when Ørsted committed to building monopiles at the Paulsboro factory if it was built, he said. EEW has since gained orders from the other offshore wind projects, among them a commitment by Atlantic Shores to make 89 monopiles at the EEW factory out of the 111 monopiles needed for the project. (See New Jersey Shoots for Key East Coast Wind Role.)

With those major hurdles overcome, the company is now “in the process of developing our sub-tier supply chain” that EEW expects will support growth well beyond New Jersey, Laurendeau said.

“The local content gives us that jumpstart,” he said. “Our New Jersey projects get us up to being a fully operational, efficient factory. But our eyes are certainly beyond that. We [have had] every project developer in the last two days up in our conference room, so there’s a lot of interest in our factory. We’ve put in proposals for almost every one of the U.S. projects that are there. So, we’re going to service the entire U.S. market from New Jersey.”

Catching Europe

That kind of calculation is going on in companies across the board as they look to the future and try to work out what is the best way to get a piece of the growing U.S. market, said Schoen, whose company, Vestas, has agreed to build a nacelle manufacturing facility at the Wind Port.

“There’s a lot of interest right now, in growing a domestic supply chain. There’s also a lot of challenges,” she said.

“We are competing with an established marketplace in Europe. And that’s the big challenge. So, if you’re looking at like how we can support this? Well, we need to play catch up. We’re a decade, two decades behind the European marketplace right now. And so, if we want big factories and a huge supply chain, it requires investment.”