The North American Council for Freight Efficiency has concluded that hydrogen will be a factor in long-distance heavy-duty trucking by enabling the industry to reduce carbon emissions in a zero-emissions future envisioned by the Biden administration.

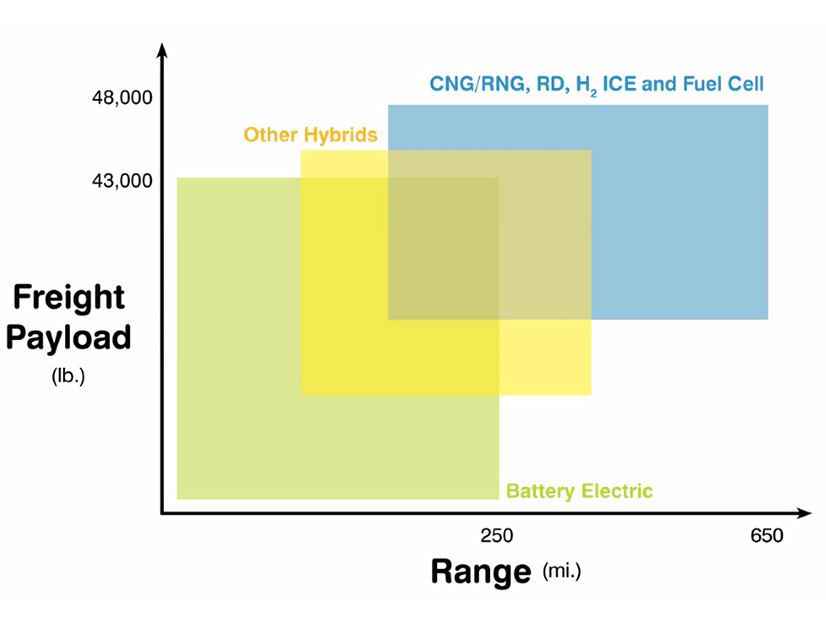

In a new report released Tuesday, a team of NACFE analysts reason that battery electric trucks, as currently designed, are not up to carrying heavy freight loads over long distances. The analysis concludes that both battery and fuel cell electric trucks will be needed, with battery trucks hauling freight locally and regionally, up to about 250 miles.

The report comes just days before the U.S. Department of Energy’s deadline for industries working with local and state governments to file applications for $7 billion in matching funds to develop regional hydrogen hubs decarbonizing heavy industry. DOE envisions beginning with six to 10 regional hydrogen hubs.

NACFE’s authors reason that hydrogen production levels will increase significantly over time with the development of the hydrogen hubs, becoming cost competitive with diesel fuel.

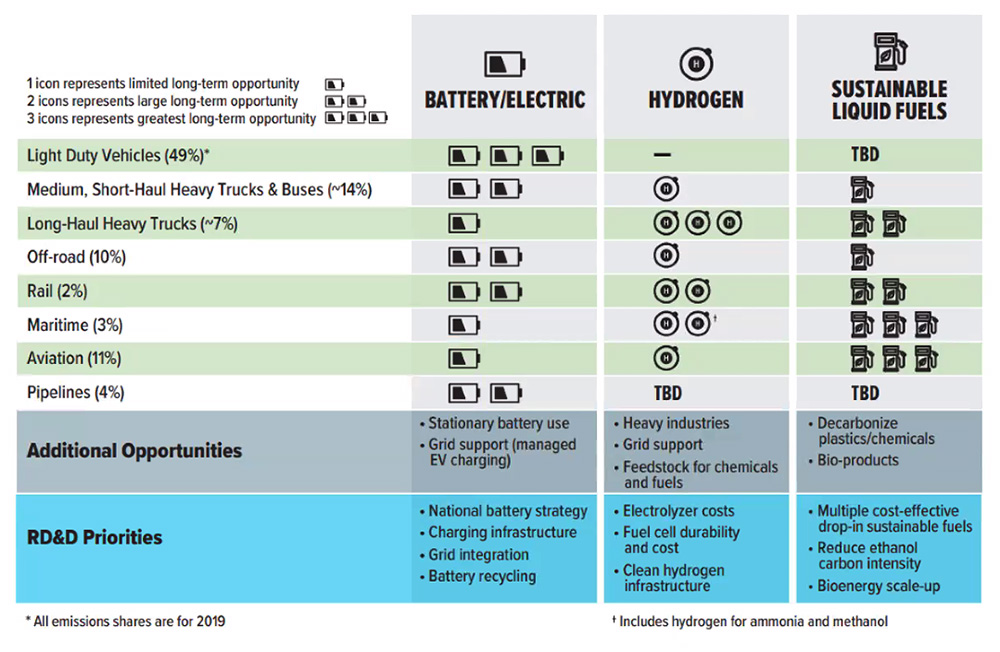

Battery electric, hydrogen fuel cells and sustainable liquid fuels will each have a role in transportation. | NACFE

Battery electric, hydrogen fuel cells and sustainable liquid fuels will each have a role in transportation. | NACFE

What the report does not say is whether the long-anticipated heavy-duty hydrogen fuel cell systems will be superior to the just emerging re-engineered diesel engines designed to run on hydrogen.

“Two paths are emerging: fuel cell electric and new hydrogen internal combustion engines,” the study asserts. “Hydrogen is not optimum for all duty cycles. Hydrogen fuel cell tractors are, however, the only viable zero-emission solution currently proposed for one-for-one replacements for diesel in the future of long-haul heavy-duty trucks.”

In previous studies issued over the past five years, NACFE focused mainly on battery electric trucks, including large trucks. And in real over-the-road testing in which a small number of fleets participated, NACFE concluded that electric fleets making deliveries over prescribed routes not exceeding 250 miles could handle the job.

Mike Roeth, NACFE | NACFE

Mike Roeth, NACFE | NACFEPrevious NACFE studies did not include converted and re-engineered diesels because none was commercially available or even discussed publicly. Cummins, a long-time engine builder, has not only been designing an engine to burn hydrogen but has also begun building electrolyzers to produce clean hydrogen. President Biden visited a Cummins plant on Monday to mark that buildout.

Mike Roeth, executive chairman of NACFE, said that while the new study demarcated the distances each technology was capable of handling, the organization has not ruled out the use of hydrogen fuel cell trucks for use in short hauls.

“In rural areas, it might be easier to get a hydrogen truck to a [refueling] site than create electricity,” he said.

Asked whether the report included a cost comparison of the three technologies — battery, fuel cell or re-engineered engines — Roeth said it “is just to early to tell.”

He explained that fuel cell vehicles require additional cooling systems over vehicles with engines because fuel cells produce a lot of waste heat when producing electricity.

“But the battery packs are also a big cost.”