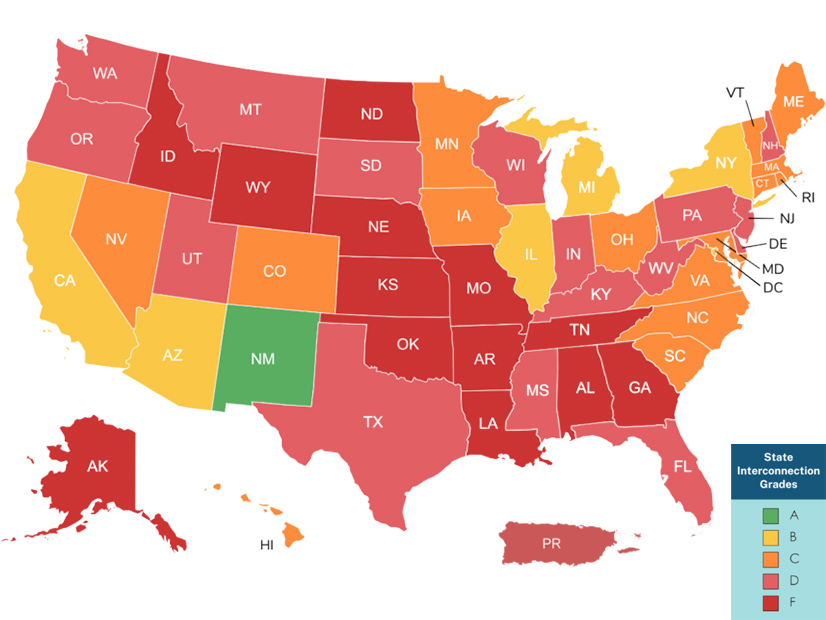

New Mexico is the best place in the U.S. for getting distributed energy resources (DERs) hooked up to the local distribution system, according to a new interconnection scorecard from the Interstate Renewable Energy Council (IREC) and Vote Solar.

The state is the only one that earned an “A” on the recently released Freeing the Grid scorecard, which is based on states’ adoption of key policies and best practices that can streamline approvals, increase efficiency and reduce costs for the interconnection of DERs.

“One of the great things about New Mexico is they had a very robust stakeholder engagement process … and they really overhauled the rules,” incorporating many of IREC’s recommended best practices, said Mari Hernandez, assistant director of regulatory programs at the nonprofit. New Mexico is also the only state to include provisions aimed at incentivizing and streamlining interconnection for projects that will benefit disadvantaged or underserved households, she said.

“That is something we wanted to signal is really important,” Hernandez said. “Our hope is to figure out more ways to think about equitable access and interconnection, and how to make sure we’re considering that within interconnection rules.”

Whether on transmission or distribution systems, interconnection ― the process for allowing new energy projects to connect to the grid ― has become a major bottleneck for solar, wind and storage projects. Freeing the Grid (FTG) grades all 50 states, D.C. and Puerto Rico on whether they have adopted jurisdictionwide interconnection policies and procedures that apply to all regulated utilities.

“Interconnection is fundamental to the clean energy transition,” Hernandez said. “So, we really believe that what’s included in interconnection procedures is a good indication of whether a state is set up to support clean energy growth.”

But according to the FTG scorecard, a majority of states aren’t adopting the necessary policies and best practices. Following New Mexico, only six states received a B ― Arizona, California, the District of Columbia, Illinois, Michigan and New York ― while 15 squeaked by with a C. A total of 30 were given Ds or Fs.

Those results indicate “real disarray across the country,” said Sachu Constantine, executive director of Vote Solar. “A lack of consistency, a lack of transparency, a lack of best practices across the whole country, and this comes at a critical moment when you look at what the [Inflation Reduction Act] is doing, what it’s signaling about the direction we want to go.”

The landmark legislation, signed into law last August, provides billions in tax credits for solar, wind and energy storage, both grid-scale and distributed, as well as manufacturing tax credits to support the build-out of domestic supply chains. The IRA also ensures many of these credits will be available through 2032, to provide certainty for the industry.

But, Constantine said, the impact of those dollars could be undercut “if we don’t have clear, transparent, useable interconnection standards.”

Freeing the Grid outlines 10 best practices, ranging from “rule applicability” — meaning that interconnection rules cover all distributed generation, including energy storage — to “dispute resolution” — that is, having a process in place to resolve disputes over the upgrades a utility may require a developer to make or pay for.

States are almost evenly split on the storage issue: 24 include storage in their interconnection rules, while 26 don’t. A similar gap appears on dispute resolution, where 28 states have a process for resolving disputes but only 13 require their public utility commissions or other entities to provide ombuds services to track and facilitate the dispute resolution process.

Uneven DER Landscape

Long and costly interconnection processes can delay or sink a DER project, particularly if a utility asks a developer to pay for millions of dollars in system upgrades. A recent study of storage interconnection processes found that in Massachusetts alone, more than 1,600 storage or solar and storage projects had either incomplete or withdrawn interconnection applications in 2022, versus fewer than 400 complete or approved. (See Report: Storage Projects Stymied at Distribution System Interconnection.)

The state received a C from FTG, partly because it does not include storage in its general interconnection rules.

Developing best practices to streamline interconnection of distribution-level solar, wind and storage is another point of resistance, especially from utilities, Constantine said.

“Historically, utilities have had to keep the lights on,” he said. “That’s all they really thought about, and modern technology, like these distributed technologies, kind of upset that paradigm a little bit because now other generators and different kinds of end users are trying to connect into this grid. There are some quality and inertia [issues], but they are operating to older standards and older practices.”

For example, only five states have adopted interconnection regulations that specify a date by which DERs must comply with IEEE 1547-2018, the industry standard for ensuring the safe interconnection and interoperability between DERs and utilities’ electric power systems.

The figures on other key streamlining measures also reflect the uneven DER landscape developers face across the country. Rooftop installations under 10 kW are eligible for a simplified review in only 17 states. FTG found only two states where projects can receive streamlined processing based on their export capacity, as opposed to their nameplate capacity.

Basing interconnection on export capacity can be critical for storage projects because some utilities base their evaluations of such projects on worst-case scenarios rather than on how they actually operate. While most storage projects charge during off-peak hours, a utility might require studies assuming they will only charge during high-demand peaks.

Constantine said he believes part of the problem is the gap between the speed at which technology is advancing and utilities’ traditional aversion to risk and change.

“Part of what we’re seeing in these grades is simply the time it takes for a utility to turn itself around,” he said. “Technology has caught up, and utilities are still trying to … understand that they can operate safely, that they can operate efficiently based on the technical capabilities of the technology that we’re deploying. …

“We’re 10 years on from the major ramp-up in the solar market, and we’re already several years into the battery era. We can’t really say with a straight face that we don’t know how these things are going to operate. We know how they are going to operate, and the standards ought to reflect that.”

A Higher Grade for Hawaii?

While state regulations provide an important benchmark, both Hernandez and Constantine acknowledge that FTG does not always capture the interconnection policies and practices of individual utilities, Hawaii being a major case in point.

FTG gave the state a C but noted that its “updated interconnection practices … have not been reflected in the state’s interconnection tariffs.”

Hawaii was among the first states to adopt a 100% renewable energy target — 2045 — and with its self-contained island grids and high levels of rooftop solar, the state has been a pioneer in DER planning and integration. According to Hawaiian Electric, the state’s main utility, rooftop solar now provides just under 15% of the state’s power, or close to half of all renewable power across the islands.

But rooftop also represents more than 90% of all solar installations in the state, and Hawaiian Electric has periodically come under fire for interconnection delays, such as in 2015, when it was faced with a backlog of 3,000 projects.

“We didn’t have a lot of the tools we have in place now,” said Blaine Hironaga, a supervisor for the utility’s distribution planning. “Hosting capacity was somewhat getting off the ground, and we were concerned about the amount of penetration that was hitting the grid. … So, it was taking some time to do those reviews. … We didn’t have a good process in place to conduct the reviews at the volume we were receiving.”

Fast forward and Hawaii has adopted performance-based ratemaking, under which Hawaiian Electric receives incentives for meeting specific interconnection goals. The state also has a range of rate plans for solar owners, in some cases limiting how much power they can export to the grid.

Ken Aramaki, director of transmission, distribution and interconnection planning, said interconnection reviews can be processed in 15-20 days, relying on “more advanced modeling” of the distribution system and “hosting capacity analysis.”

“We do sort of annual hosting capacity analyses of all the circuits, so we know how much can be added to the distribution system,” Aramaki said. The utility also uses a range of databases to cross-check its technical reviews, he said.

To further streamline interconnection, Hawaiian Electric also performs group or cluster studies, with “a model checkout process ahead of time” to ensure all the members of a group have all the information and system modeling needed before the utility begins the group study, Aramaki said.

The FTG score “doesn’t recognize the level of sophistication required and the technical complexities to get these high renewable numbers,” he said. “We do really complex modeling ahead of the rest of the industry because we have to.”