The White House and Department of Energy on Friday unveiled a new interagency task force aimed at reaching the administration’s ambitious goals for the deployment of clean hydrogen to decarbonize a range of hard-to-abate industrial and transportation sectors, from steel production to heavy-duty trucking and aviation.

The Hydrogen Interagency Task Force (HIT) “will be designed to … fully leverage the strengths and capabilities of the U.S. government to develop technologies, implement policy and overcome barriers to building a clean hydrogen economy,” said Mary Frances Repko, White House deputy national climate advisor, during a Friday webinar.

The task force will include representatives from 11 federal agencies, including EPA and the departments of Transportation, Labor, Interior, Agriculture and Commerce. Repko will co-chair the group with DOE Deputy Secretary David Turk, who laid out the administration’s timetable for clean hydrogen deployment.

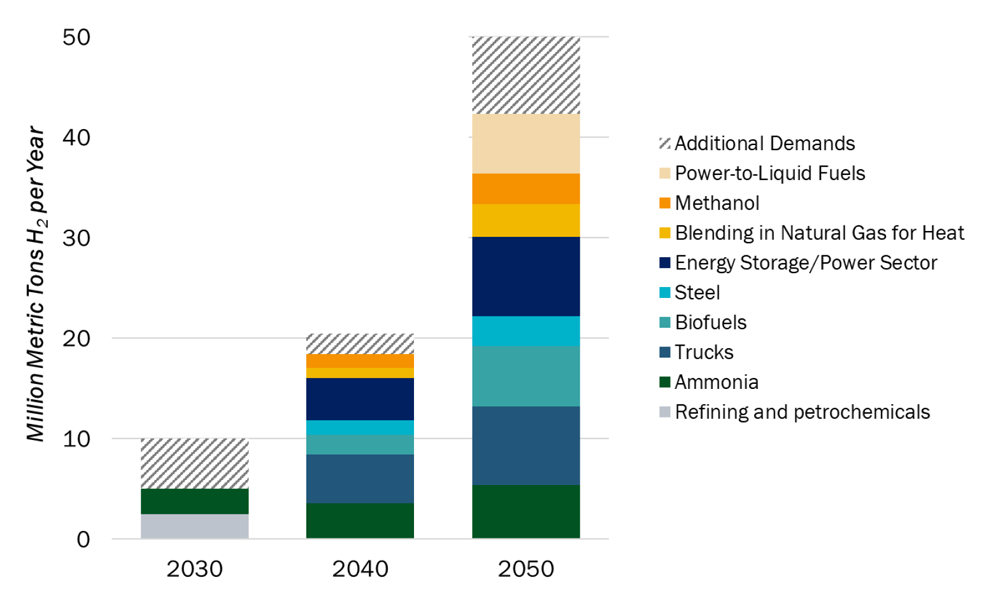

The U.S. currently produces about 10 million metric tons (MT) of hydrogen a year, most of which “comes from fossil fuel sources without carbon capture,” Turk said. “By 2030, we want to produce the same amount of hydrogen, but we want to do it with clean hydrogen. … By 2040, we want to double that … from 10 million MT to 20 million MT, and by 2050, we want to go to 50 million.”

Reaching that goal would produce enough hydrogen to power all the buses, trains, planes and ships in the U.S., and could help the U.S. cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 20% by 2050, he said.

“So, this is not a nice-to-have,” Turk said. “This is not just a sideshow. This is part of the main event going forward.”

One of the core pillars of the agency’s strategy is building out a network of regional clean hydrogen hubs, with the first six to 10 funded with $7 billion from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). Applications for the funding were due in April, and Todd Shrader, director of project management for DOE’s Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations, said the awards would be announced “in the fall.”

The purpose of the hubs is to co-locate commercial-scale production and end uses “to demonstrate different use cases from different feedstock diversity, meaning different power supplies,” Shrader said. Once DOE helps build the first six to 10 hubs, he said, “what that really does is [it] encourages and shows the lessons learned to industry to build plants 11 through 100.”

An analysis from Resources For the Future found that the applicants competing for the DOE money largely are multistate, private-public collaborations, with many planning to use renewable energy to produce clean hydrogen.

The National Clean Hydrogen Strategy and Roadmap, released in May, lays out three pillars for scaling clean hydrogen, beginning with zeroing in on high-impact end uses, such as heavy-duty transportation. The second is cutting costs so clean hydrogen is competitive with the fossil fuels used for other critical end uses, and the hubs are the third, said Sunita Satyapal, director of DOE’s Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technologies Office,

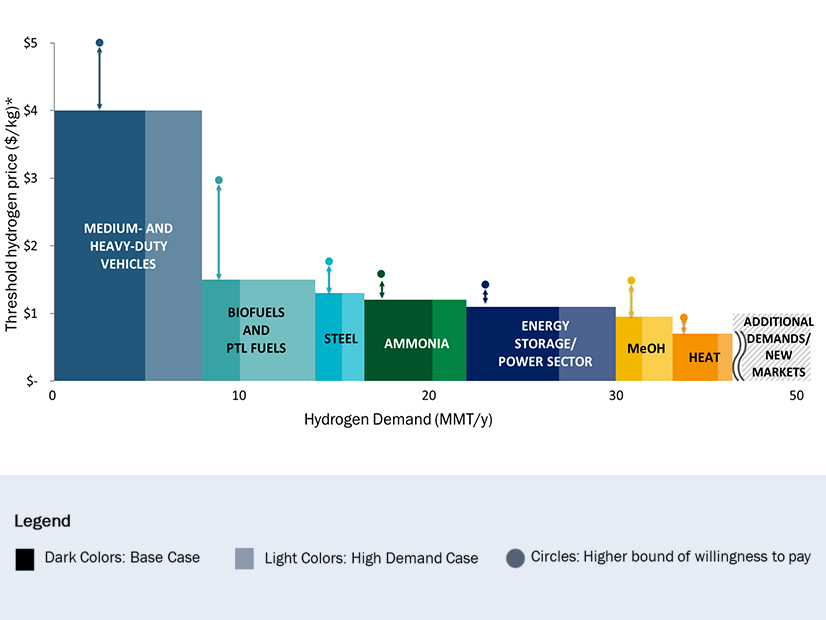

DOE’s main initiative for cost cutting is the Hydrogen Shot, one of the agency’s Energy Earthshots, which all are aimed at reducing costs for new technologies needed to reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. The goal for the Hydrogen Shot is to decrease the cost of clean hydrogen from about $5/kg to $1/kg within a decade.

Clean hydrogen is produced by using electrolyzers, powered by electricity, to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. The equipment is expensive and not yet produced at the scale needed for significant market growth.

But the lower the cost of clean hydrogen, the more sectors will open up to its use, Satyapal said. For example, getting the cost to $4/kg would make hydrogen competitive for heavy-duty trucking, she said.

“If we can get 10 to 15% of all the trucks using hydrogen fuel cells, that will enable 5 to 8 million MT of hydrogen in terms of demand,” she said.

Clean hydrogen at $2/kg could compete with biofuels, and at $1/kg, demand for clean hydrogen could grow in steel production, ammonia and energy storage, she said.

Production vs. End Use

Friday’s webinar and the announcement of the interagency task force seemed designed to fill the gap in concrete results on clean hydrogen as President Biden celebrated the first year of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The law provides a production tax credit of up to $3/kg for clean hydrogen, which has been a draw for new investment.

While promoting administrative initiatives like the new taskforce, speakers at the webinar also acknowledged the challenges ahead, calling for an “all-of-industry” commitment to match Biden’s all-of-government strategy.

While passage of the IRA led to a doubling of announcements for new clean hydrogen projects in the U.S. by the beginning of 2023, more than half were for production versus about a third for end use, according to DOE. Projects in planning or under construction almost entirely are in hydrogen production, leaving the market decidedly lopsided.

“It doesn’t really do any good to have lots of production capacity if there’s not end-use capacity or an end user for the product itself,” Shrader said.

DOE recently announced $1 billion in IIJA funds to be dedicated to building demand for clean hydrogen, with the government possibly acting as a “market maker,” buying hydrogen from the hubs and selling it to others. (See DOE to Invest $1 Billion to Build Demand for Clean Hydrogen.)

Other obstacles cited in DOE’s recent Pathways to Commercial Liftoff: Clean Hydrogen report include a lack of “midstream infrastructure” — pipelines or other means of transport — for situations where hydrogen production and end use are not collocated, and the need for increased scaling of renewable energy.

Without adequate renewables — wind, solar and nuclear — the report predicts that fossil fuels with carbon capture and storage (CCS) could be used to produce up to 80% of clean hydrogen by 2050, as opposed to fossil fuels with CCS and renewables producing 50% each.

With utilities and other industries looking at mixing natural gas and hydrogen, pipeline safety also could be an ongoing concern. Mary McDaniel, of the Department of Transportation’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safe Administration (PHMSA), said her agency has been tightening regulations on pipeline leak and rupture detection and mitigation.

“We have 1,500 miles [of pipelines] that are pure hydrogen at this point,” McDaniel said. “We’re going to be looking at hydrogen blending for pipelines as it gets more use in the pipeline line system; so, making sure that we have the infrastructure in place for that. Then we’ll be able to make any leak detection and response for those leaks.”