A pilot program using smart EV charge management to smooth distribution loads and improve demand response has been so successful a utility is adopting the program permanently before completing the pilot. The interim results of the U.S. Department of Energy-funded pilot were shared at a workshop at RE+ in Las Vegas earlier this month.

“Baltimore Gas and Electric found the initial residential pilot results are impactful and have included a permanent smart charge management program in their multi-year plan,” said Joshua Cadoret, senior project manager at Exelon, which received an award from DOE for a Smart Charge Management (SCM) pilot program with three of its utilities: Baltimore Gas and Electric, Delmarva Power and Light and Potomac Electric Power.

The pilot study, which is ongoing, includes about 3,000 residential EV customers with more than 3,600 vehicles as well as 850 public chargers throughout their territories as of Sept. 7. Commercial EV fleet owners also were targeted, but only one has been recruited successfully to date.

The SCM pilot recruited Tesla owners to enable their cars’ charging to be throttled to reduce peak demand and encourage off-peak charging. WeaveGrid software shares the utilities’ signals with the vehicles. The EV owners received a $10/month electric bill credit, equal to 10% of an average monthly bill, and were able to override the demand response request up to four times each month. The public charging pilot program offered customers two options: the default opt-in where charging is throttled at certain times and charged at a discounted cost/kWh or opt-out to get the full capacity of the charger at the standard rates.

Managed charging aims to solves two problems utilities face: their distribution systems’ ability to cope with an increasing number of EVs and the utilities’ need to respond to renewables, said Shane O’Quinn, senior director of business development at WeaveGrid, a company whose software optimizes EV-grid integration for utilities. “Whenever you have a large number of EVs coming online where 80% of the charging is happening at the residential level, and the residential distribution network is designed to support really relatively modest loads at the household, we’re ultimately going to get to a point to where we have distribution system challenges.”

EV charging incentives can be designed with the goal of spreading the load into times that lower the need for grid upgrades, O’Quinn said: “One of the first things you have to consider is how are people actually going about charging their EVs today and where do you ultimately want them to be in terms of how they charge in the future?”

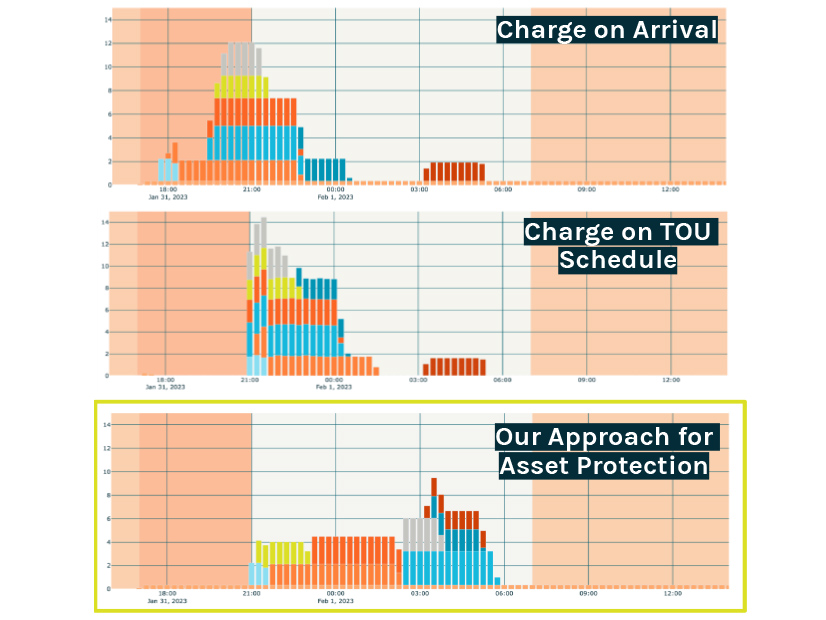

The default for most EV drivers is to plug in their car when they arrive home from work, which usually coincides with peak demand as most housholds turn on HVAC and use appliances at the same time. This is shown in the first scenario in Weavegrid’s graph, which shows eight cars on a single distribution feeder plugging in when they return from work, although one works late shifts so that car draws on the grid later than the others.

“Many utilities take the next step and think about how they might be able to implement time-of-use rates which can shape behavior so that people are starting to charge after the on-peak times are over,” O’Quinn said. That can help the drivers manage the cost of electricity but may not be optimal for the utility.

The initial stage of the residential pilot tested the ability to use SCM to move charging to off-peak times and resulted in 96% of the more than 40,000 charging sessions being done off-peak. While the drivers may plug in when they get home, the SCM works with vehicle telematics so charging begins when off-peak rates start, the second scenario in the graph.

“There’s another technique that can more actively push the charging into periods that are beneficial for you as a utility. For instance, we can utilize an approach where we’re smoothing out the charge levels on various distribution system assets, making sure that you’re not overloading transformers, for instance,” O’Quinn said, “or you might be able to push the charging into a period where you can soak up renewables on the grid.” The third scenario in the graph shows SCM being used to even out load on distribution grid assets.

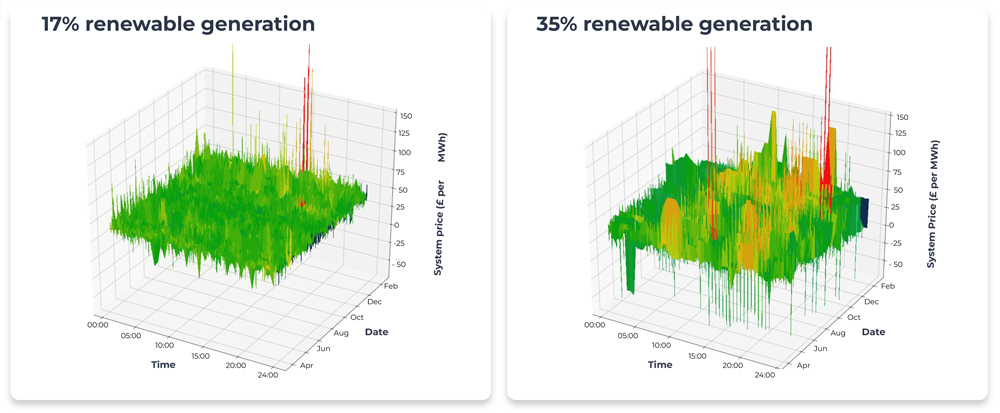

Helping utilities use managed charging to absorb renewables on the grid is driven by economic realities, said Russell Vare, who heads automotive OEM partnerships for Kaluza, a vehicle-to-grid software provider. Using data from the UK as an example, he showed how the move from 17% to 35% renewables resulted in a substantial increase in price volatility.

While regulated markets may not have that degree of price volatility, this data shows the need for utilities to use EVs to absorb peak renewables supply.

The pilot also looked at potential cybersecurity risks and vulnerabilities of EV chargers and vehicle telematics software, according to the Phase 1 Review distributed by the Smart Electric Power Alliance (SEPA).