To meet its ambitious goals of reducing greenhouse gas emissions 60% by 2031 and getting to net zero by 2045, Maryland should adopt a Clean Power Standard (CPS) ― 100% carbon-free by 2035 ― increase state rebates for electric vehicles to $7,500 for low-income buyers and quadruple the installation of heat pumps for HVAC and water heating, according to the state’s Climate Pollution Reduction Plan.

The state also will have to come up with an extra $1 billion per year in public funding to pay for those proposals and the dozens of other initiatives laid out in the plan, even as it faces increasing budget shortfalls over the next few years.

Released by the Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) on Dec. 28, the plan lays out emission-cutting recommendations for every sector in the state’s economy, and to-do lists for the General Assembly and the administration of Gov. Wes Moore (D).

“The policies in this plan, if fully implemented … will nearly put an end to the fossil fuel era and accelerate the transition to a clean energy economy,” the report says.

The plan also stresses that a major portion of that $1 billion in new public spending each year “would focus on providing financial support to Maryland’s low-, moderate- and middle-income households and small businesses,” with the primary goal of improving equity and affordability.

The state’s energy transition will be “intentional but also practical and methodical,” the report says, laying out “a sustainable path where incentives are provided at key decision points to consumers.” For example, when a furnace needs to be replaced, state incentives ― added to federal tax credits from the Inflation Reduction Act ― could cover up to 100% of the cost of installing a heat pump for low- and moderate-income households and 50% for middle-income households.

Clean energy advocates have mostly praised the plan but cautioned that the nitty-gritty details of implementation remain to be worked out.

The plan is “scientifically sound; it’s technically strong,” said Kim Coble, executive director of the Maryland League of Conservation Voters. “Where we are disappointed is that … there isn’t a plan to implement it. There’s [no] action. There’s not a funding source. There’s not even a discussion about how we are going to determine a funding source.”

Rather, she said, the plan lays out an extensive list of tasks for lawmakers and different state agencies, without providing concrete next steps.

-

- The Maryland Energy Administration (MEA) would determine a legal framework for the CPS and whether the needed regulations could be implemented under its existing statutory authority.

- The MDE would begin drafting new regulations to establish zero emission standards for heating equipment, with final regulations to be released by the end of 2025.

- Responsibility for providing new point-of-sale incentives for EVs and EV chargers would be split between the Department of Transportation and MEA, respectively.

- The Public Service Commission would have the role of initiating a proceeding this year “to require natural gas utility companies to develop plans to achieve a structured transition to a net-zero economy in Maryland.”

- As a first step toward the CPS, the General Assembly would update the state’s existing Renewable Portfolio Standard specifically to exclude solid waste incineration, which is currently defined as renewable power.

The Elephant in the Room

People’s Counsel David S. Lapp, the state’s top consumer advocate, likes the plan’s focus on building electrification, which “is the least-cost path forward for customers, including residential customers,” he said. Heat pumps can replace both home heating and cooling equipment, Lapp said.

PSC action on gas utility planning is critical, but not enough, he said. “The legislature at some point, the sooner the better, will need to get involved.”

By continuing to approve long-term investments by the gas utilities, “the state is effectively subsidizing fossil fuel infrastructure investments that are entirely contrary to virtually everything you see in the MDE report,” Lapp said.

Even before the plan came out, the Maryland Chamber of Commerce raised concerns that any new regulations and fees could result in businesses moving “their operations to other states with less restrictive carbon emissions reduction regulations to avoid the high costs of compliance. Businesses in those states can also emit greenhouse gases then import their products into Maryland, creating an unfair playing field for Maryland businesses,” it said in an October letter to MDE.

But Stephanie Johnson, founder of the newly formed Maryland Renewable Energy Alliance, countered that “the plan does a really good job of identifying the problems the state is facing, and it provides an overview of the potential solutions.”

“The elephant in the room is the cost and timeline,” Johnson said. “I think there’s a political disconnect between the desire to move towards clean energy and the political will to make that happen, and I don’t think the plan gets at that problem.”

Getting to 60%

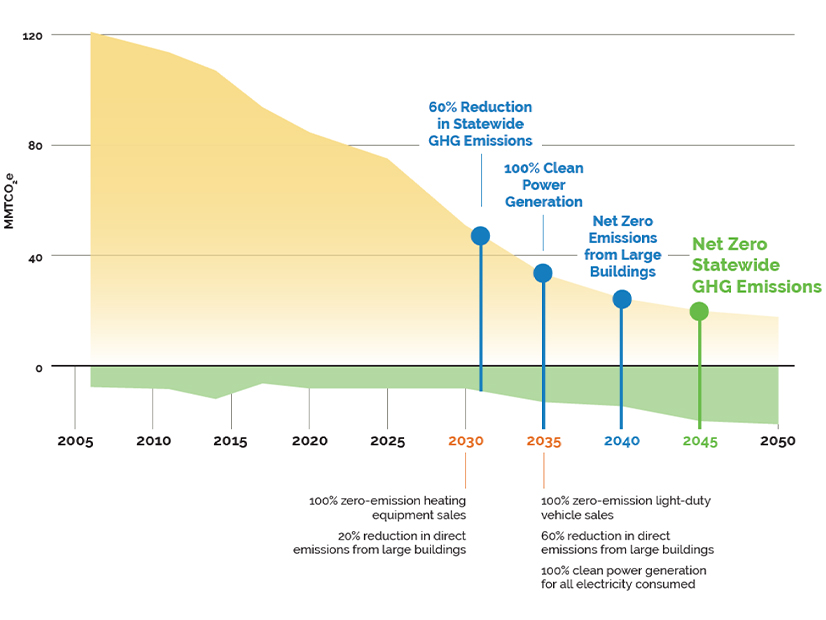

The passage of the Climate Solutions Now Act (CSNA) in 2022 put Maryland on the map as a state with some of the most aggressive GHG emission reduction goals in the nation ― 60% below 2006 levels by 2031 and net zero by 2045 ― making it a potential model for other states.

The law also required MDE to formulate a plan ― to be submitted to the governor and the General Assembly by the end of 2023 ― to reach those targets while creating jobs and economic benefits for the state. Moore upped the ante with his commitment to decarbonize the state’s electric power system by 2035.

MDE released a preliminary plan laying out multiple options for implementing the CSNA in June ― also required by the law ― followed by a comment period that included a series of public meetings across the state. (See Maryland Climate Report Lays out Pathways to Achieving Goals.)

Maryland is already halfway to the 2031 goal, according to MDE, and existing policies could get the state to 51%. In the past year, the state has adopted the Advanced Clean Cars II rule, requiring all new light-duty vehicles sold in the state to be zero emission by 2035. The General Assembly also passed a bill making the state’s community solar pilot a permanent program.

Getting to 60% could be achieved by a mix of policies focused on specific sectors ― like the CPS and zero emission heating standards ― as well as economywide initiatives, such as a carbon fee or statewide cap-and-invest program, the report says.

On the benefit side, MDE estimates that reaching net zero by 2045 could generate $1.2 billion in public health savings while creating 27,400 jobs and increasing personal incomes by a total of $2.5 billion. Factoring in heat pumps, EVs and other energy-saving measures, individual households could save as much as $4,000 per year, the report says. Statewide GHG emissions would drop by 646 million metric tons by 2050.

Such dramatic cuts in emissions will not keep Maryland and its residents from experiencing the potentially catastrophic impacts of climate change. “Maryland’s climate will get warmer, wetter and wilder,” the report says.

In 50 years, the state’s climate could be more like Mississippi’s, and by the end of the century, “islands throughout the Chesapeake Bay and much of Dorchester County will be lost to the sea,” the report says. Located in the middle of Maryland’s Eastern Shore, Dorchester is considered “ground zero” for sea-level rise in the state, according to a 2018 report.

Money

Beyond the impacts of climate change, the greatest challenge ahead for Maryland is money. The ambitious targets in the CSNA did not come with any funding, and figures from the state’s Department of Legislative Services show budget gaps expanding to $418 million in 2025 and to as much as $1.8 billion by 2028.

Maryland lawmakers must not only raise an extra $1 billion per year for clean energy and emissions reductions but do so without leaving consumers to pick up the tab through higher electricity rates or other expenses, the report says.

“I don’t know that everybody’s figured out how to budget for climate change yet,” said Del. David Fraser-Hidalgo (D), pointing to impending budget cuts for the state’s Department of Transportation. The state also needs to increase teacher pay and hire more police officers, he said.

“These are things that have been a known issue for a while now,” Fraser-Hidalgo said. “So, to come with a report and say, ‘Hey, we need another billion dollars for the next 10 years’ … is a challenge for the General Assembly, and the governor to find creative ways to come up those monies to make those changes.”

Lapp said, “It’s going to take a variety of state policies to support what needs to happen, [and] that should not be subsidized, in effect, by ratepayers. It should be supported through other government policies because paying for a lot of the policies through rates is regressive.”

“A key approach should be taxing polluters … getting money from fossil companies,” said Del. Lorig Charkoudian (D). She points to the plan’s recommendations for a carbon fee or a statewide cap-and-invest program, with some of the money raised used to offset the effects of any price increases on low- and moderate-income consumers.

Maryland already participates in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), a consortium of 11 East Coast states that sets ever-decreasing caps on emissions from power plants that burn fossil fuels and holds quarterly auctions to sell allowances to plants to offset their emissions.

At the last auction of 2023, on Dec. 6, Maryland received more than $50 million from allowance sales, according to figures on the RGGI website. Now, it is pushing the other states in the consortium ― many with their own emission-reduction goals ― to set the emission caps even lower in their upcoming program review, expected this year.

A statewide cap-and-invest program would go beyond power plants to cap emissions and sell allowances to other major industrial or commercial GHG emitters.

Other recommendations in the plan include green revenue bonds and pollution mitigation fees for both interstate and in-state drivers. Interstate drivers would pay a “clean air toll” by mail to help mitigate the emissions their vehicles produce while traveling in the state.

For Maryland residents, the report envisions a pollution mitigation fee paid as part of the registration process for vehicles that burn fossil fuels. The state is considering joining the growing number of states that have increased registration fees for EVs to make up for lost gas taxes, used for highway maintenance.

If the EV fees are established, the pollution mitigation fee and clean air toll for gas-burning cars should be set at comparable amounts, the report says.

Maryland also must go after federal funding available from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the IRA. The report calls for all state agencies to “work closely with local governments, nonprofits and community-based organizations to ensure Maryland is competitive for federal climate action implementation funds and build capacity for local-level implementation.”

The General Assembly

As the General Assembly opens its 90-day regular session Jan. 10, it must pass several laws before agencies can implement the plan’s top priorities.

For example, before Maryland can set up a cap-and-invest program, the legislature would need to pass a new law that would allow the state to regulate emissions from the manufacturing sector, something it is currently prohibited from doing.

The plan also calls for legislative action to update the state’s energy efficiency program, known as EmPOWER Maryland, to allow the PSC to set emission-reduction goals for electric and gas utilities and “require the utilities’ programs to facilitate beneficial electrification of fossil fuel heating equipment.”

Another proposed bill would require new multifamily housing to be built either with EV chargers already installed or with the wiring necessary for installation. A new law would also be needed to allow state EV rebates to be paid at the point of sale.

Charkoudian sees low-hanging fruit in a bill that would remove waste incineration as an eligible form of renewable generation in the RPS as a first step toward the CPS. Although previous efforts to update the RPS have failed, she said, “that absolutely can be done this year. … The idea that we are subsidizing trash incineration as a renewable source … is absurd, and it’s unjust, and it flies in the face of everything we’re trying to do with our environmental justice policies.”

Both Charkoudian and the Chesapeake Climate Action Network (CCAN) are hoping for progress on a bill called the Responding to Emergency Needs from Extreme Weather (RENEW) Act, which was introduced by Fraser-Hidalgo last year but did not get past an initial hearing. The bill proposes that major fossil fuel companies pay a series of annual, fixed fees to compensate the state for the impacts of extreme weather events exacerbated by climate change.

“It requires every company that has emitted more than a billion tons of greenhouse gas emissions cumulatively between 2000 and 2020 to pay [fees] to the state of Maryland,” said Jamie DeMarco, CCAN’s Maryland director. If passed, the bill could raise close to $1 billion per year for 10 years, he said.

Fraser-Hidalgo plans to reintroduce the bill this session, and both he and DeMarco said they are going to make a major effort to get the bill to the governor’s desk.

The LCV’s Coble says the General Assembly should approach funding with a two-step strategy, beginning with green bonds as a short-term solution. The second step would be a cap-and-invest program, which she said, “is going to take some time because it has to go through a whole regulation and rulemaking process. I would like to see the administration start that effort now because it probably wouldn’t be effective for several years.”

Both Coble and DeMarco said direct support from Moore could be essential in getting the needed laws through the legislature. The governor has not yet released a public statement on the MDE plan.

Fraser-Hidalgo said the funding issue could be holding Moore back from a full commitment to the MDE plan.

“I think he would like to do that. I think he will do that,” he said. “These are expensive transitions ― electrification and decarbonization. They’re very expensive [and] haven’t really been done before and not in the way we’re talking about.”

“We want to see Gov. Moore do three things,” DeMarco said. “One is [to] speedily and effectively implement all the executive actions … in this report. Then we also want to see him pick specific revenue raisers and fight for [them], and we also want to see him support specific legislation in Annapolis that aligns with the legislative goals” in the plan.

Coble has a similar challenge for the governor and the legislature. “We’ve got a strong base to work from here; and we need leadership, and we need a sense of urgency, and then it will happen,” she said. “I mean, we’re the state of Maryland. Of course, it will happen.”