Top legislators in Massachusetts this year hope to pass a major climate and energy bill, which could bring significant permitting and siting reform, and boost transportation and heating electrification.

“The clock is ticking,” Sen. Mike Barrett (D), Senate co-chair of the legislature’s Joint Committee on Telecommunications, Utilities and Energy (TUE), told NetZero Insider. The legislature has until the end of July to reach a consensus.

“It’s my hope that we’ll have something by the springtime on the floor of the House,” said Jeff Roy (D), House co-chair of the TUE committee.

The TUE committee was responsible for a large portion of the omnibus climate bills passed in 2021 and 2022 under the administration of Gov. Charlie Baker (R). These bills contained wide-ranging provisions aimed at expediting the state’s clean energy transition, including setting emissions limits for the major sectors of the state’s economy and directing the procurement of 5,600 MW of offshore wind capacity.

The general template for the bills, which presumably will carry over into 2024, was for the House and Senate to pass distinct legislation compiled from smaller bills introduced earlier in the session. The two chambers then would form a conference committee to reconcile differences between the bills, with the resulting bill eventually passed by both chambers and sent to the governor.

“It’s going to be a really interesting time,” said Kyle Murray, director of state program implementation at the Acadia Center, a climate-focused nonprofit. Murray praised the steps taken in the previous two bills but added that “we’ve got so many areas we still need to cover.”

Permitting and Siting Reform

One major theme emerging for the session is reforming permitting and siting processes for clean energy projects and infrastructure.

“In order to get all this infrastructure built, and to get it built in a timely manner to have an impact on the goals we set, we need to do something about the permitting and siting process,” Roy said.

For most projects today, “it’s going to take you three to five years to get the shovel in the ground because you have to do so many steps in the permitting process,” Roy said. “We’re looking at legislation to revamp the process and bring it down to more like 18 months.”

Roy has introduced a bill that would consolidate the state and local permitting process under a new “electric decarbonization infrastructure permitting office.” The bill also would introduce a roughly six-month process for the office to respond to applications.

S.2113/H.3187, a separate bill aimed at expediting the development of clean energy while protecting environmental justice communities, would introduce significant reforms to the state’s Energy Facilities Siting Board. The bill is a top priority of the Mass Power Forward coalition, a coalition of many of the state’s most influential climate and environmental organizations.

The proposal is intended to prevent new polluting infrastructure in “the same communities that have been dumped on for decades and decades because of systemic racism,” said Claire-Karl Müller, coordinator of Mass Power Forward. The bill simultaneously would speed up the review process for solar, wind and geothermal projects.

“It’s important to do this transition quickly, but we want to make sure it’s done equitably,” Müller said.

The state’s Commission on Clean Energy Infrastructure Siting and Permitting also is due to publish its final legislative and regulatory recommendations at the end of March. (See Massachusetts Announces Permitting And Siting Reform Commission.) Created by Gov. Maura Healey (D) in the fall, the commission is aimed at cutting timelines and barriers for clean energy projects.

Transmission Planning

The state’s Clean Energy Transmission Working Group (CETWG), created in 2022 climate law, released its final report at the end of December, calling for a “more comprehensive, proactive and forward-looking transmission planning processes.”

The CETWG recommended the legislature amend state laws to allow the Department of Energy Resources to “competitively solicit and select proposals for transmission to deliver clean energy generation to help achieve the Commonwealth’s clean energy requirements, beyond existing authority to solicit and select transmission related solely to offshore wind.”

The final recommendations also called for increased efforts to reduce transmission needs through load growth including time-of-use rates, demand response and energy efficiency. The CETWG also advocated for a regional analysis of the potential of alternative transmission technologies (ATTs).

As an offshoot of their work on the CETWG, Roy and Barrett also introduced bills in the House and Senate that would require utilities to consider ATTs including grid-enhancing technologies, advanced reconductoring and energy storage when planning upgrades to the transmission system.

“We both filed that legislation, which is probably a good sign that it’s something we will agree on this session,” Roy said.

Heating Decarbonization and Electrification

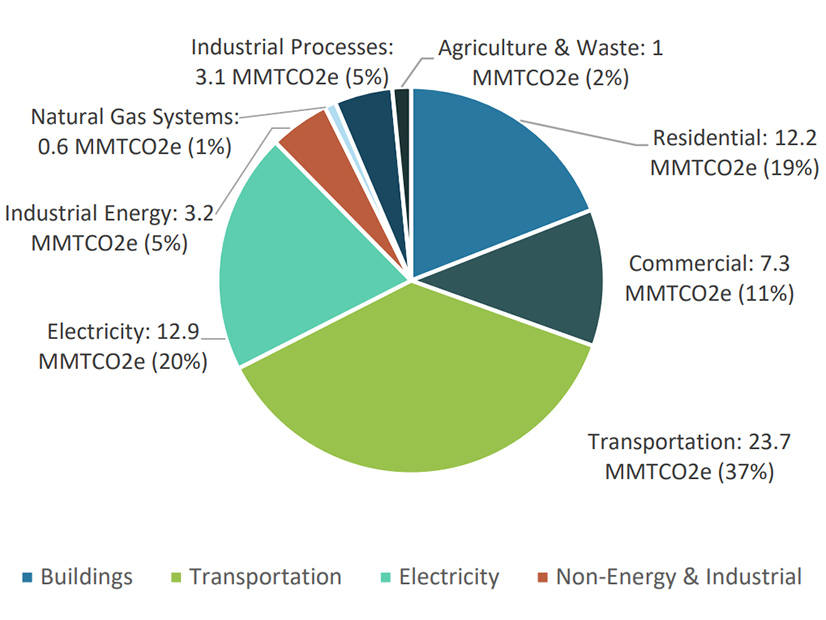

The legislature also is considering a number of bills aimed at supporting heating electrification. Data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration shows that natural gas consumption in Massachusetts increased by about 8% in 2022, and natural gas remains one of the largest sources of carbon emissions in the state.

Legislators so far have submitted a wide range of proposals aimed at cutting gas emissions, from a moratorium on the further expansion of the gas system to bills that would promote blending alternative fuels like renewable natural gas and hydrogen into the network.

For Senate TUE Chair Barrett, one key component is creating “linkage” between the expansion of the electric distribution system and the contraction of the natural gas system.

“Building out the grid — while it’s very important to delivering green juice everywhere it needs to be delivered — is going to make the utilities very wealthy because they make a rate of return on all construction projects,” Barrett said. “What do you ask of the utilities as you deliver vast riches to them? It can’t be zero.”

He noted that approval of increased investments in the grid could be coupled with requiring the utilities to speed up the interconnection of clean energy projects and downsize gas operations.

Barrett also expressed optimism that two programs passed in previous legislation — a new municipal opt-in building code which incentivizes electrification and a 10-town pilot program which allows municipalities to ban fossil fuels in new buildings — will start to make a significant dent in the state’s gas consumption in 2024.

However, both TUE chairs indicated they’re not likely to pass new provisions to directly prohibit the expansion of the state’s gas system, such as an expansion of the 10-town pilot program or a statewide moratorium.

“I think we need time for that pilot project to take place and to get some reporting and data back,” Roy said.

For climate activists pushing for a moratorium on new infrastructure, the verdict on new natural gas infrastructure is clear.

“It is more than beyond obvious that we need to stop building fossil fuels,” said Müller of Mass Power Forward. “We know we can’t be expanding gas.”

The legislature also could consider changes to the state’s Gas System Enhancement Program (GSEP), which is aimed at replacing old pipes to reduce methane leaks. The program has faced criticism for facilitating billions in new gas system investments that could become stranded assets because of the state’s decarbonization efforts. The program ultimately could cost ratepayers over $40 billion, according to a 2021 report.

The 2022 climate bill created a GSEP stakeholder working group, which is tasked with drafting recommendations on changes to the program that would align it with the state’s climate laws. The group released a draft outline of its recommendations in December and likely will publish its final recommendations at some point this session.

The Department of Public Utilities also included legislative recommendations in its recent order on the “Future of Gas” proceeding (DPU 20-80), which requires gas utilities to consider nonpipe alternatives when planning new infrastructure investments and discourages further expansion of the gas system. (See Massachusetts Moves to Limit New Gas Infrastructure.)

The 20-80 ruling also highlighted an apparent contradiction between the state’s required emissions targets and a law passed in 2014 that requires the DPU to “review and approve proposals designed to increase the availability, affordability and feasibility of natural gas service for new customers.”

The DPU recommended the legislature repeal this law to allow the department to “pursue fully its mandate to prioritize reductions in GHG emissions along with safety, security, reliability of service, affordability and equity.”

Speaking at an event in December, DPU Chair Jamie Van Nostrand said the state should reconsider laws that give residential and commercial customers the right to gas service.

“Customers are still going to be provided the essential utility service of heat, but it may be provided in some way other than gas,” Van Nostrand said. (See Clements Outlines Further Steps to Ease Interconnection Woes.)

Transportation

Transportation decarbonization also is likely to be on the docket this session, with the legislature weighing proposals to boost electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure and increase ridership on mass transit.

Roy has been especially vocal about the need for more robust charging infrastructure, and he highlighted the state’s ambitious goal to have 900,000 EVs on the road by 2030 (compared to about 70,000 in 2022).

“That’s going to require a huge investment in charging infrastructure,” Roy said. He introduced a bill in early 2023 that would direct state agencies to forecast EV demand and optimal charging locations and require the electric utilities to submit plans for the grid upgrades needed to meet this demand.

Murray of the Acadia Center stressed the importance of securing funding for public transport in the state. According to a recent assessment by the Massachusetts Taxpayers Foundation, the state would need to invest an additional $2 billion annually through 2036 just to make all the necessary repairs for the existing system. This excludes any potential expansion, resilience or modernization efforts to help the state meet its climate goals.

“We need a more stable funding source for the MBTA [Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority]. I really do think we need to address that at some point in the very near future,” said Murray, while acknowledging the added difficulty of the state’s current financial troubles. Gov. Healey recently proposed a $375 million budget cut to stave off an impending shortfall.

Caitlin Peale Sloan, vice president for Massachusetts at the Conservation Law Foundation, echoed the need to properly fund the MBTA to help reduce total vehicle miles traveled. She added the state also needs to think long term about how to electrify trains and buses, particularly those that operate in environmental justice neighborhoods.

“When it comes to mass transit, it’s a balance,” Peale Sloan said. “We don’t want to make mass transit more difficult and more expensive to users — we want more people using it. But we need to have the big picture plan and start to get that moving.”