ALBANY, N.Y. — The networked heating systems New York wants to test on a pilot scale hold promise for the environment and society but are taking time to design.

A March 6 conference brought together many of the people advocating for thermal energy networks (TENs), one of the tools the state is considering to reduce its carbon footprint.

Buildings account for a third of New York’s carbon dioxide emissions, and TENs hold the promise of reducing that by using less energy and using it more efficiently.

The Public Service Commission in 2022 ordered the seven largest investor-owned utilities to propose pilot projects that point the way for a permanent regulatory structure for utility TENs.

Eighteen months later, the order has accomplished its initial goal — yielding a greatly varied set of proposals that could broadly inform future efforts — but the proposals are still at the first of several stages of PSC review. (See NY Utility Thermal Energy Network Pilot Program Simmers.)

And the potential framework for what would be an entirely new class of utility in New York only recently has been released in draft form.

The title of the summit — “Scale Up! Decarbonizing NY’s Neighborhoods” — accurately conveyed its mood: The room was full of supporters.

The Building Decarbonization Coalition was one of the organizers, and its New York director, Lisa Dix, called the state’s first-in-the-nation utility TENs enabling legislation “one of the most important efforts to date to usher in the clean energy transition for buildings at scale in this state.”

Simple and Complicated

Some potential tools of the clean energy transition — long-term battery storage, small modular nuclear reactors, economical but clean hydrogen generation — would require technological or engineering leaps to be usable.

TENs are straightforward by comparison: Move heat from where it is unwanted to where it is needed within a group of buildings via fluid in pipes. Less energy is used, less is wasted.

A project might be more or less complicated, depending on whether it includes details such as geothermal bores and heat pumps, or if there is a motherlode of wasted heat nearby, such as a data center.

But the technology for accomplishing these tasks is known and mature. And as Jared Rodriguez of Emergent Urban Concepts pointed out, municipalities have decades of experience moving water from place to place through pipes. “It’s not rocket science.”

The more daunting tasks in New York are shaping up to be organizational:

-

- getting enough property owners on board in a neighborhood.

- siting the infrastructure.

- deciding who pays for it.

- building it strategically so natural gas infrastructure can be retired or at least not expanded.

- transitioning gas workers to thermal jobs.

- maintaining union representation.

- ensuring economic and environmental benefits for disadvantaged communities.

- creating a new class of state regulated utility.

- making the entire process fit into the larger picture of the clean energy transition.

This is why the state is starting with pilot projects, and why development of those pilot projects is proceeding methodically.

Department of Public Service Chief of Staff Jessica Waldorf said: “It has taken us centuries to build the systems that we have in place, and we cannot make a wholesale shift of our energy systems and the way that customers choose to use them in an instant.

“Advancing projects like these at scale in existing communities as part of neighborhood-level decarbonization efforts is a new frontier, and one that will require partnership of many different stakeholders, like all of you in this room, to effectuate.”

She said, however, that progress to date makes her confident of progress to come:

“Make no mistake — the transition to cleaner sources of energy has been taking place for decades, where we have witnessed transitions away from dirtier sources of energy, like coal or oil in the power sector, to movements in our building sector to make our buildings significantly more energy efficient and in greatly reducing emissions for our transportation sector.”

Varied Perspectives

Jessica Azulay, executive director of the Alliance for a Green Economy, said TENs are just one tool in the clean energy transition.

Their value is that they help bring about a managed transition, in which everyone in a defined area can switch away from gas. The alternative path to building decarbonization is individual homeowners installing heat pumps, which is an unmanaged transition, and leaves the residents unable to afford heat pumps shouldering an increasing share of the cost of the gas infrastructure.

“Obviously this is not an either-or; our transition is going to be multifaceted, but I think we’re going to be much better off if we use thermal energy networks as a major tool in our toolbox,” Azulay said.

She noted the rate of heat pump adoption in New York would have to increase tenfold for the state to reach its building decarbonization milestones through heat pumps alone.

Indu, the director of energy at the nearby University at Albany, described the situation at her campus, which essentially is a small city with a population that sometimes exceeds 20,000 in a diverse collection of 100-plus buildings spread across 500 acres.

It’s an ideal place for TENs, and in fact there are two TENs in operation, but they are fossil powered and only about 70 to 80% efficient. A $30 million upgrade was included in the 2023-24 budget to change this, and better achieve the promise of TENs.

A new high-efficiency electric centrifugal and heat recovery chiller connected to a new geothermal well field, new hot water system and new piping will reduce campus gas use 15%.

“So, this idea of saying OK, seasonal thermal storage, moving it around, I don’t want to be burning gas or oil to create heat and I have this heat already,” Indu said. “All I have to do is store it and move it from one place to another. When you start thinking about it like that, [instead of] the 70 to 80% efficiency system, you’re talking 350 to 700% efficient systems.”

It’s a win-win-win for the campus, community and planet, she added, and the efficiency is such that the operating budget will not increase.

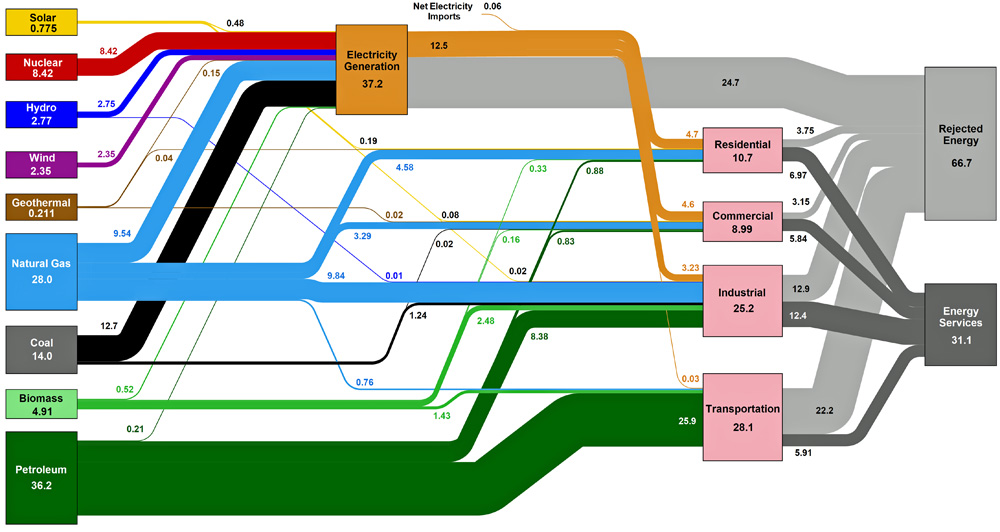

Vikas Anand, Danfoss vice president of climate solutions North America, keyed on the opportunities presented by efficiency. He cited the famous chart compiled by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory showing more than half of U.S. energy consumption evaporating in the form of waste heat.

“So, the opportunity for us to manage waste heat is so immense, that we can meet our climate goals as a country, I will say, very easily,” Anand said.

The question was raised about how large commercial properties fit in these systems.

“Most residential consumers don’t voluntarily pay for green,” Trent Berry of Reshape Infrastructure Strategies said. “That is more prevalent in the commercial sector because they’re competing for tenants” that have net-zero goals. Other factors making TENs attractive to commercial building owners include energy standards for new buildings and local regulations requiring energy efficiency or decarbonization.

New York is the second-most unionized state, and officials include labor-friendly provisions in many of their initiatives. But where does the next generation of union members come from?

John Murphy of the New York State Pipe Trades Association said it’s important the transition be framed as a path to the future rather than the end of an era for certain trades. People need to see a future they can plan a career around.

“I think what’s most important is that when we have a certainty of work, we know that there’s a pipeline of work ahead. It allows building trades unions to recruit from the community, to be able to train the workforce — can’t happen without that work certainty,” Murphy said.

“I can tell you, even for the workers and the members in my industry, when they say, ‘Where is our transition,’ we need to show them this is the path, this is the future, and it’s nothing to be afraid of, you can work here.”

Eric Walker of WE ACT for Environmental Justice sought to focus on the many New Yorkers using energy they can’t afford, to the detriment of their health:

“How are we going to think about these … technocratic solutions as ways to meet basic needs for people who are often not even discussed in the conversation around what our energy and economic development agendas are in the state?

“I think of thermal networks really as one of many approaches to meeting a series of basic needs,” Walker said. “We have a really serious problem around energy affordability, and energy security across multiple types of buildings and demographics within the state. There are 3½ million [low- to moderate-income] households in the state that essentially qualify for some form of energy assistance.

“And that is that’s really kind of scary, with about $1.7 billion of utility arrears that remain outstanding. And that to me signals a real need to invest in the kinds of interventions at the system level that provide the energy trilemma … sustainability, security and affordability.”

Which leads once again to the question of who pays for it all.

Much of the expected benefit of decarbonization would be societal and much of it would play out unevenly over years or decades in the form of avoided costs.

The bill for the transition, by contrast, is concrete and inevitable. The only uncertainty is how much of it will fall directly on individual ratepayers and how much of it will be embedded in other things, such as taxes, fees and consumer costs.

Walker said however the bill is allocated, it is worth the cost.

“What we have is an environment where first cost is scaring people without any sort of contextualization for what the actual overall benefit is to every ratepayer in the system, every building owner in the system, to every community across the state,” he said. “If we do nothing, the costs only get bigger; if we do something, the net cost is much better than the first cost. It’s all about investment. … There’s no dollar that we spend at a societal level that doesn’t benefit us in some way.”

The Timeline

Dix said later that the utility TENs pilot program is progressing well — even quickly by the standards of the regulatory world — but a lot of questions about its details are unanswered and some of the questions haven’t even been asked.

Other details are moving targets, such as whether the state will remove the requirement that gas utilities connect new customers to gas lines for free if they are within 100 feet of the line. That’s on the table in budget negotiations.

Dix said she appreciates the two-pronged approach. The theory behind the utility TENs bill was to get pilots moving forward, she said, “because we needed to learn from them, because we really are creating new utility models, an integration of the electric and gas utilities, maybe water. We’re creating all kinds of new customer engagement plans; we’re creating different ownership mechanisms.” Once the projects get going, the regulatory process is “going to be a year or two to get those rules all final and ready to go.”

One thing that gives Dix hope is that the Utility Thermal Energy Network and Jobs Act, the impetus for the pilot projects and the forthcoming TENs regulatory structure, received near-unanimous legislative approval in 2022. Moreover, it wasn’t embedded in a budget package, the back-door route by which many contentious measures become law in New York state.

“This was a very long effort where we worked together to focus on the solutions that unite us rather than divide us,” she said.

The Public Service Commission set Case No. 22-M-0429 in motion in September 2022 with an order that the state’s seven largest investor-owned utilities propose one to five pilot TENs projects.

By September 2023, they had submitted 14 widely varied proposals with a price tag of up to $435 million.

At their meeting that month, the PSC judged those proposals good first efforts but insufficient in detail, and it issued an order providing guidance on how best to refine the proposals.

In February 2024, the Department of Public Service published its proposal for initial utility TENs rules and invited public comment. The latest technical conference — on potential performance metrics — is scheduled for March 19.