MORGAN CITY, La. — With decades of experience servicing offshore oil and gas rigs, Louisiana manufacturers are finding offshore wind a natural expansion for their businesses.

Louisiana companies making the jump hosted visitors from the 2024 International Partnering Forum for a review of their work to date and a preview of their plans to come April 22.

Each has a different niche they hope to seize, but there was a common message in their presentations: We’ve got this.

Oil and gas are the polar opposite of wind power in more than one sense, but there is some commonality in both industries’ skills and tools.

A fine example is the first U.S. offshore wind farm, Block Island Wind — which Louisiana oil workers helped build.

That synergy is what marine fabricators in Louisiana and elsewhere on the Gulf Coast are looking to exploit.

The hard assets are in place; waterfront land is cheap and plentiful; the all-important human infrastructure and institutional knowledge already exist.

However, offshore wind is less an energy transition than an energy addition in their eyes. They expect oil and gas to thrive for a long time to come, regardless of how many state and national proclamations set net-zero or emissions-free targets for one year or another.

On April 25, the closing day of IPF24, a report suggesting ways for Louisiana to parlay its offshore expertise into wind power was released by the Southeastern Wind Coalition, GNO Inc., Center for Planning Excellence and The Pew Charitable Trusts.

“Louisiana Offshore Wind Supply Chain” quantifies the state’s strengths and the potential it holds for the growing industry.

Port Hopes to Grow

Cindy Cutrera, economic development manager for the Port of Morgan City, said the facility is a crossroads for all forms of transportation, with a small airport; direct rail access and future interstate access to the rest of the nation; and water access to much of the nation and world via the Atchafalaya and Gulf Intracoastal waterways.

“We are at the focal point of waterborne transportation in four directions,” she said.

An assortment of marine industrial activity already is in place along those waterways, Cutrera said, and expansion is planned.

“It’s expected to be completed by the summer of 2026 and that’s going to increase our dock space [with] about 900 feet for waterfront access,” she said, “and the laydown area is going to increase from about 200,000 square feet to about 500,000.”

Offshore wind has little presence so far at the port — Oceaneering International and InterMoor are the extent of it — but there is room to grow.

“For the Port of Morgan City or South Louisiana right now, we see the fabrication side — you’re in the hub of fabrication here,” port Executive Director Raymond “Mac” Wade said.

“Louisiana is still trying to figure it out. I think we might be a little behind, but we are trying to push to get wind energy off the Louisiana coast,” he said. “But if nothing else, a lot of fabrication can be done here. I don’t care where it’s shipped, I just want it done using our waterways.”

Wade noted InterMoor recently shipped an order of suction piles from its Morgan City shop to Guyana.

Expansion Strategies

However eager Gulf Coast manufacturers and officials are to supply the offshore wind industry, the region has been slow to embrace it for electricity.

Last year’s federal auction of wind energy lease areas in the Gulf drew minimal interest, although Louisiana itself secured agreements for two wind farms in state waters in late 2023, shortly before then-Gov. John Bel Edwards (D) left office.

Wayne St. Pierre, InterMoor’s facility manager at Port Fourchon, noted the port is going to be the site of Louisiana’s first commercial-scale onshore wind turbine, and is ramping up to dredging to a 50-foot depth, which would allow the largest offshore wind installation vessels to dock.

Here again, wind energy joins fossil fuel rather than replacing it: The port also is the proposed location for a new LNG export terminal.

“Those vessels that do install windmills are really large. They need a place like this, and we are very close to the Gulf of Mexico. That puts us in a strategic spot to develop this facility,” St. Pierre said.

“It’s going to be wind-driven, obviously, but there’s also going to be a need for topside repair, stuff like that,” he added.

He noted there is not an immediate need: The large wind turbine installation vessels requiring a deepwater berth are foreign-flagged and cannot dock to pick up equipment, thanks to a 104-year-old protectionist law known as the Jones Act.

Instead, a workaround is used — load the equipment onto a barge and take the barge out to the installation vessels. But fans of the Jones Act and opponents of offshore wind are trying to stamp out such subterfuge, St. Pierre said.

“They’re already concentrating on that,” added Carrie Adams, InterMoor’s U.S. general manager. “They’re attempting to make that change to say if you take something off that barge and you put it on that vessel and you move that vessel at all to do an installation, you have violated the Jones Act.

“It is difficult for all of us, not just what the renewables industry looks like, it’s also the oil and gas industry,” she said. “It is becoming more and more of a hindrance to all of us.”

Tom Fulton, head of renewables and mooring development for Acteon, InterMoor’s parent company, said the company built its offshore expertise in oil and gas and moved to offshore wind.

Floating wind is the latest focus for Fulton and Acteon, which is using InterMoor’s experience with moorings as an entry point. It does not have any “steel in the water” for the new floating wind sector but it is close, he said.

Floating wind is more expensive and complicated than the fixed-base wind turbines being installed off the Northeast U.S., and there are few floating wind farms worldwide.

Fulton also pointed out there is no supply chain to produce certain floating wind components at scale. Yet.

“A lot of challenges, but it’s all doable with time, money and innovation,” he said.

Undersea Opportunity

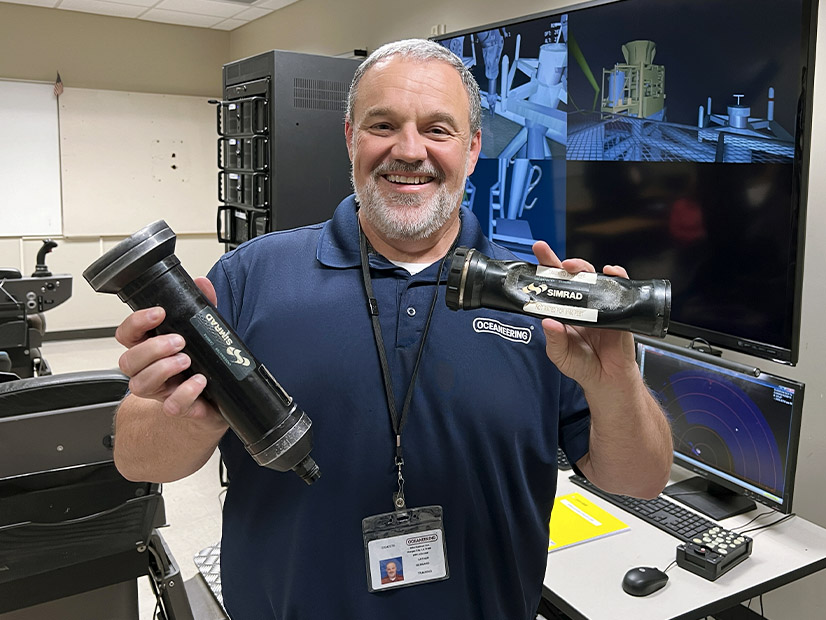

Oceaneering International gave a look at its Morgan City facility, where it maintains some of its remotely operated vehicles and trains their operators.

Oceaneering designs its own hardware and software in an iterative process driven by employee and customer input, senior manager David Macnamara said.

While the machines are not terribly difficult to operate — “Even Dave Mac can fly them,” he said — they are quite expensive, and they are working on critical underwater infrastructure. So, there is little margin for error.

The company invests four weeks of training in new employees and gives them advanced training as they gain experience and demonstrate competency.

Two flight simulators fill a large portion of a classroom.

“You don’t need a degree to come in here to do this,” Macnamara said. “We’ve had little kids come in on tour and just blow us away with the simulators. There’s a job for you in 10 years.

“We get a lot of young people out of the military,” he added. “The Navy has fantastic A schools and C schools for electronics.”

Instructor Andrew “Putt” Bernard, a retired high school teacher who started a second career at Oceaneering two years ago, uses two once-identical cameras as teaching tools. One is normal, the other was crushed like an empty beer can when the ROV it was mounted upon was taken too deep.

The Isurus ROV is rated for 3,000 meters. “You can always fly lower — once,” Macnamara said.

Oceaneering has not worked on the earliest U.S. offshore wind projects, Macnamara said, but the emerging industry is a natural progression for the company.

“The tools are a very good common fit,” he said.

Oceaneering sees expanding into offshore wind as a growth strategy on top of oil and gas as well as a defensive strategy in case the offshore oil and gas sector does shrink, Macnamara said.

“I don’t think we as a company think we’re going to be ending fossil fuels anytime soon,” he added. “We want to be a player in those [offshore wind] markets as those markets develop.”

Building More Boats

Metal Shark Boats has been building a wide array of work, emergency and military vessels on the Gulf Coast for 36 years. Crew transfer vessels for offshore wind facilities are now taking shape in the company’s Franklin, La., boatyard.

Vice President of Commercial Sales Carl Wegener apologized in advance to the Europeans in the contingent from IPF24, then debunked some skepticism about U.S. shipbuilding capabilities.

“When I hear the Europeans say, oh there’s not enough shipyards in the United States to build all the CTVs we need, bull! I could have four more of these going here right now,” he said, pointing to a gleaming catamaran towering in one of the work bays.

Wegener cited the fleet of 32 ferries plying the East River in New York City. The offshore CTVs that Metal Shark is building are of a similar design but with heavier plating to withstand the controlled collisions they will make with monopile towers.

“We built 22 of the 32 right here in 38 months,” he said.

Wegener said his company cannot supply CTVs for some projects because of states’ efforts to steer work to local companies. He does not think those policies can continue — it would be impossible to build and staff an industrial boatyard in every state that wants one.

Metal Shark has not built the offshore service vessels that are the workhorse of the Gulf oil and gas industry, but it has benefited nonetheless from that sector’s heavy presence.

“We’re really lucky that the [offshore oil and gas industry] started here,” Wegener said. “We’ve got tons of tradespeople, training programs, all the companies, the pipefitting, everything that supports oil and gas, there’s a lot of it in this area. It’s just a culture of workforce and that’s really the advantage the Gulf Coast is going to have over the Northeast.”

He added: “Is it hard for us to find labor? Yeah, but not nearly as hard as for my friends up in Massachusetts, Rhode Island and other areas.”

Additional IPF24 Coverage

Read NetZero Insider’s full coverage of the 2024 International Partnering Forum here:

Central Atlantic Region Prepares for OSW Development

How Best to Address OSW’s Effects on Fisheries

Interior Announces Updated OSW Regs, Auction Schedule at IPF24

Moving Offshore Wind Beyond Contract Cancellations

New York Starts Another OSW Rebound