The U.S. Department of Energy estimates that existing and recently retired nuclear power sites could host an additional 60 GW to 95 GW of new nuclear generation.

DOE also said an additional 128 GW to 174 GW of new nuclear capacity could be built near existing or recently retired coal-fired facilities.

In its 2023 report “Pathways to Commercial Liftoff: Advanced Nuclear,” the department estimated the U.S. would need 200 GW of additional nuclear capacity by 2050 to meet the growing demand for electricity and the growing emphasis on emissions-free generation.

“A good chunk of that could come from a familiar place,” Michael Goff, acting assistant secretary for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Nuclear Energy, wrote Sept. 9 in introducing the new report.

“Evaluation of Nuclear Power Plant and Coal Power Plant Sites for New Nuclear Capacity” finds that 41 operating and retired nuclear sites could accommodate one or more new large light-water reactors rated at 1,117 MW for a total of 60 GW of new capacity.

Using advanced reactors rated at 600 MW would bring the total to 95 GW, as more reactors could be built on more sites.

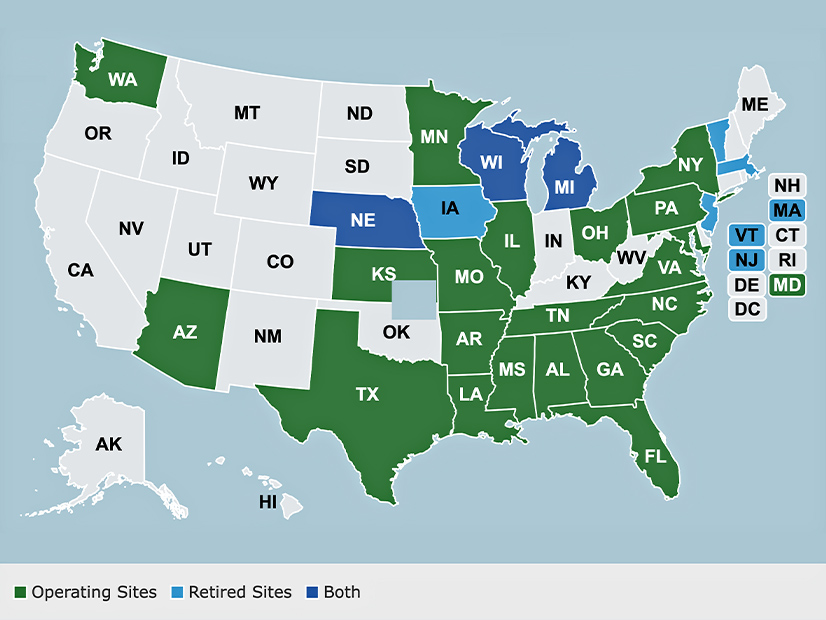

For its analysis, DOE examined 54 operating and 11 recently retired nuclear power plant sites in 31 states.

To determine suitability for expansion, it examined site footprint and acreage, aerial analyses, utility plans, a siting analysis tool developed by Oak Ridge National Laboratory, availability of cooling water, proximity to population centers or hazardous facilities, seismic risk and flood hazards. Researchers from Oak Ridge and Argonne National Laboratory contributed.

Important tangible considerations such as politics and finances were not on the list of factors considered, though Goff acknowledged that capital costs will be a key factor in decisions about nuclear plant construction.

He cited a study showing the majority of people who live near nuclear power plants consider them good neighbors. And there is hope that a concerted buildout of new nuclear plants will create economies of scale that limit the cost of new nuclear construction, which has seen exorbitant cost overruns.

For coal-burning plants, which are being retired or scheduled for retirement at a steady rate, the study looked only at sites with a nameplate capacity of at least 600 MW that are active or were retired after 2019. It assumed retired plants had not been converted to natural gas and that their licenses to provide power to the grid were still in effect.

Replacing coal with nuclear in a timely fashion could benefit the surrounding communities economically and environmentally and take advantage of existing workforces. A 2022 DOE report delved further into the opportunities and challenges that would surround such conversions.

Goff stressed that this new analysis is preliminary. “Utilities and communities will need to work closely together to make the decisions on whether to build a new plant,” he wrote.