As Joe Biden’s presidency nears its end, Resources for the Future (RFF) reflected on the work of the federal Interagency Working Group on Energy Communities in a report released Nov. 5, examining how the lightly funded entity worked and where it fell short.

The IWG was established one week after Biden took office in 2021 with Executive Order 14008. It was meant to organize the federal government’s response when communities lose out on the economic activity from a retiring power plant or other fossil fuel business. Organized by the Department of Energy, it also included the White House’s Office of Management and Budget, and Domestic Policy Council; the departments of Treasury, the Interior, Agriculture, Commerce, Labor, Health and Human Services, Transportation, and Education; EPA; and the Appalachian Regional Commission.

The White House had two main motivations for establishing the committee: showing its commitment to communities and workers that have historically powered the U.S. economy, and identifying the challenges and supporting the goals of coal-dependent communities around the country.

“Establishing the IWG in the first week of the administration … indicated a commitment to addressing the specific challenges faced by fossil energy communities and workers in the broader context of concern for places ‘left behind’ economically,” the report says.

Federal programs often face similar issues, but they have not developed a unified strategy to address many of them, often working in silos, according to the report. The IWG was meant to help coordinate the delivery of resources and expertise to coal communities.

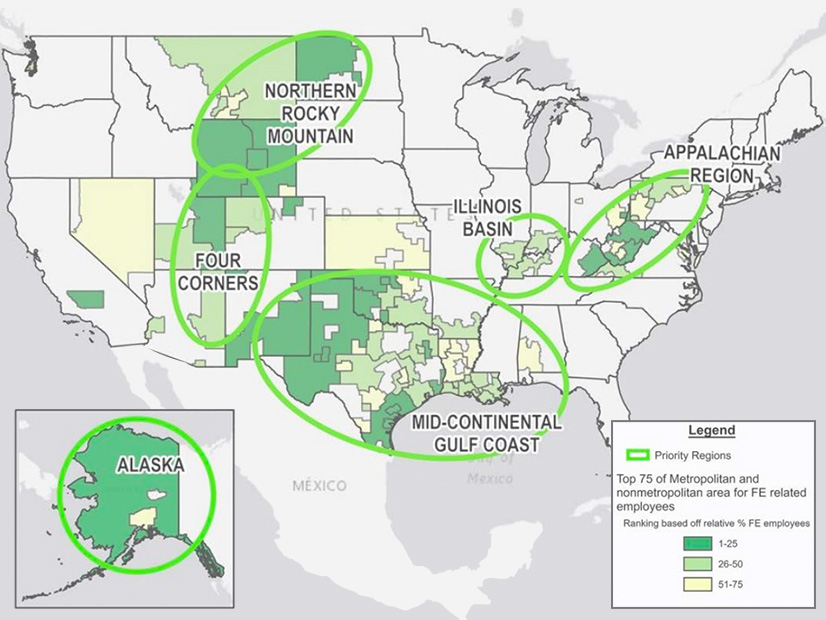

The IWG used data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics to identify areas that were highly dependent on coal, oil and natural gas for local employment (with most of its focus on coal communities). The identified areas included broad regions such as the Southwest, Gulf Coast, Intermountain West, Appalachia and Alaska.

The group’s work focused on engaging energy communities, identifying federal investments to support job creation and economic diversification, integrating such programs across the federal government so communities could have a one-stop shop to access them, and identifying policy reforms and initiatives that would support their economies.

It also set up rapid response teams for Wyoming, the Four Corners region, the Illinois Basin, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Kentucky, with more under development.

“Each RRT has a coordinator from one of the IWG’s member agencies,” the report says. “RRTs meet regularly with staff from state agencies and governors’ offices and local leaders to tackle the challenges they identify. This model provides an opportunity for information to be shared across, as well as up and down, levels of government.”

The teams allow locals to become familiar with federal agencies and what they can offer, while federal staff benefits from increased understanding of local needs.

The IWG also focused on identifying federal funding set aside or prioritized through legislation, such as the $300 million from the Commerce Department’s Economic Development Administration dedicated to coal communities, $4 billion in tax credits for clean energy manufacturing, and bonus tax credits for clean energy projects.

One of the challenges identified in the effort is that federal programs are not nimble enough to meet the needs in each unique community.

“Economic reinvention is not simply a matter of identifying a new industry or new technology and inserting it into the vacuum created by the declining or departed legacy economy,” the report says. Building a new renewable energy facility, which is almost always made of components manufactured elsewhere, does little to replace lost jobs from a shuttered coal plant or mine. “Early on, IWG leadership recognized that it would be most effective when it could connect communities to tailored solutions, rather than tailor the community’s needs to a federal program.”

Communities benefit more from help when they have identified a plausible economic future, but many of them lack the capacity to create such visions of their future.

“These are the communities that need the most support: time-intensive tailored assistance, capacity building and nurturing,” the report says. “For example, local elected officials may need help identifying which programs are best suited for upgrading, expanding or maintaining water and sewer infrastructure, in part because different types of projects may be funded by different programs across multiple agencies.”

That retail-scale technical assistance can stretch the IWG’s budget, but it can also provide spillover benefits to implementing federal programs in other communities.

“Facilitating regular and direct engagement between different levels of government builds relationships and trust among community members, local leaders, federal staff and others, improving the likelihood of successful federal intervention,” the report says. “And although challenges for accessing federal funding remain in many instances, helping communities apply for federal programs has given the IWG insights into how access can be improved.”