Setting up cost floors and caps for transmission lines can help get major transmission connections between markets built, said experts in a webinar hosted by the American Council on Renewable Energy (ACORE) on Jan. 20.

The U.K. has used that method to finance major new interconnectors with different markets on the European mainland and Ireland, and advocates said it could help get interregional lines financed and built in the United States.

Using floors and caps for major transmission lines combines the investment certainty from regulated rates and merchant exposure that optimizes asset use, said Regulatory Assistance Project Principal Jennifer Chen.

“Regulated interregional transmission is challenging because balkanized planning and disagreements between neighboring authorities on shared costs borne by their respective captive ratepayers can present issues,” Chen said. “On the other hand, purely merchant financing faces challenges with upfront investment and certainty, amongst other issues.”

Cap-and-floor is a financing model that combines approaches from both with the floor offering certainty and the cap allowing trading potential to be maximized. Customers get paid back if revenue exceeds the cap over a set period, and the floor requires ratebase customers to pay to meet it when market revenues fall short.

“Projects can create more value than in a purely regulated setting. That value can be shared with customers,” Chen said. “The costs of the projects are allocated to the markets, to those procuring transmission services, instead of defaulting to captive ratepayers.”

Since being implemented in 2014, the method has led to several major transmission links between Great Britain and other countries. Great Britain is regulated by the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem), while National Grid runs the transmission system for England and Wales.

Regulators have issued several solicitation windows since 2014 and picked projects that produced net benefits and filled a need on Great Britain’s grid.

“The first interconnectors in Great Britain were developed under a merchant model where revenues were fully exposed to market risks and developers would seek exemptions from certain regulatory requirements,” said Ofgem’s Megan Jones.

Then, in 2007, the European Commission put a cap on revenue for an interconnector between Great Britain and the Netherlands called “BritNed.”

“Because of this decision to impose this additional condition, there was a risk that the merchant model, and therefore interconnected development more broadly, could become less attractive to investors and developers,” Jones said.

Working with regulators in Belgium, Ofgem introduced the cap-and-floor model in 2014 to make merchant interconnectors viable again.

“Developers are incentivized to invest in a project where the potential market value of an interconnector and the consequent revenues are greatest compared with their costs,” Jones said. “This means that there is also an incentive for developers to keep delivery and operation costs down.”

Those incentives minimize the risk that consumers will have to pay anything to ensure interconnectors’ revenue meets the floor price, she added.

Ofgem has open three solicitation windows so far in 2014, 2016 and 2022. Before then, Great Britain had four connections with neighboring countries, and since then, four more have been completed, one is under construction, and seven more have won regulatory approval, Jones said. They have created 5.3 GW of transfer capacity and see flows go both ways, though for now, Great Britain is a net importer.

“Various projects have returned revenues above the cap to consumers, and at the moment, that currently amounts to roughly 300 million pounds having been returned,” Jones said.

National Grid has participated in those solicitations through its subsidiary National Grid Ventures, said the latter’s Mark Tunney. It’s still possible to build interconnectors without the cap-and-floor model, but those projects are much rarer.

“We submit all of our various parameters into Ofgem in order to assess the cap and the floor,” Tunney said. “So, what is the capital cost we spent? What are the ‘OPEX’ costs that we anticipate? Our tax, the allowed return, is calculated by Ofgem, etc. And they form the cap and the floor.”

The revenues are measured against the cap and the floor every five years for the lines National Grid has constructed, but Tunney said that could be cut down to one year to work better with different business models.

After the lines get built, Ofgem does an audit of the construction process and its costs, and Tunney said National Grid Ventures has gotten somewhere between 97 and 99% of its project costs approved for the floor under that process. Ofgem also allows changes in the floor-and-cap parameters over the project’s life if rules and regulations change that require more spending, he added.

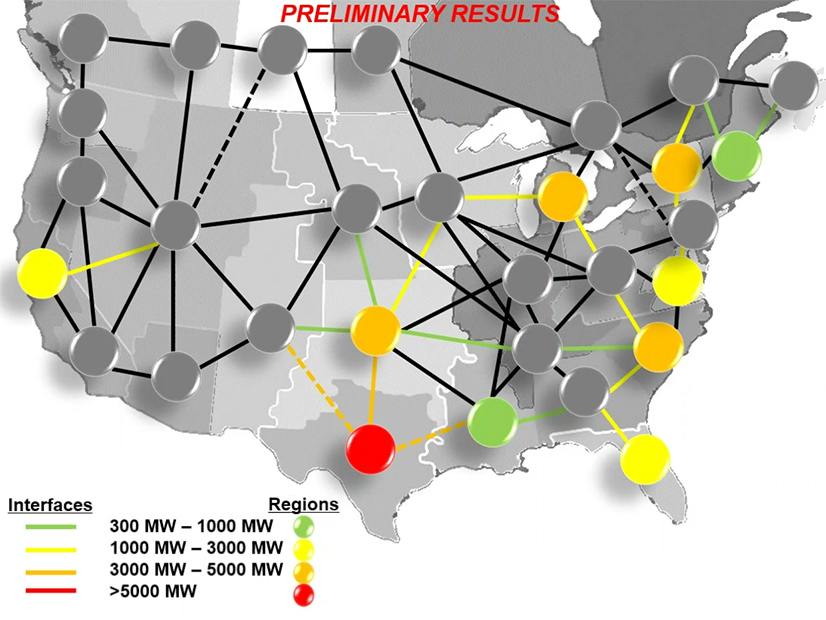

Grid United develops interregional transmission lines in the United States, which operate like the interconnectors across the Atlantic, and has been interested in using the cap-and-floor model since learning about it several years ago, said CEO Michael Skelly.

“We have talked to a number of policymakers here in the U.S. about this idea, and I think there’s some real interest out there,” Skelly said. “We would need to build momentum and so on. But the reasons that we’re enthusiastic overall because it may help us cut through the Gordian knot that we have here in the U.S. — how are we going to pay for new transmission?”

Grid United has done some calculations on different projects and found that the cap-and-floor method could lower revenue requirements for major transmissions by 30 to 40%, he added.

But getting the method in place will require some outreach to regulators so they understand how it works and, given the political climate here, the concept could use a rebrand.

“We’ll have to come up with a new name here in the U.S. because people might think this is some carbon thing, which we may have a hard time to sell,” Skelly said. “But there’s lots of clever people out there that can figure out how to sell it.”