Massachusetts could decarbonize its peaking power portfolio by 2050 through aggressive deployment of wind, batteries and demand flexibility, according to a new analysis by a group of environmental nonprofits.

The report found that while decarbonizing the peak would increase electricity costs, overall costs would be comparable to or less than fossil alternatives when accounting for climate and health effects.

“The analysis confirms that decarbonizing peak demand is not an abstract aspiration but a practical and necessary component of Massachusetts’ clean energy transition,” the authors wrote.

Synapse Energy Economics conducted the analysis for the Massachusetts Clean Peak Coalition, with the intention of supporting discussions on the topic at a working group convened by the Massachusetts Office of Energy Transformation.

The consulting firm estimated 2050 costs for clean-peak, business-as-usual and alternative-fuel pathways. It assumed a load profile based on current demand levels plus new load from heating and transportation electrification. Based on historical weather data, it estimated that the state would need an average of 9 GW — and up to 13.9 GW — of peaking capacity by 2050.

The clean energy pathway assumed 24% demand flexibility, which would require aggressive deployment of “a suite of load reducing and load shifting measures” including efficiency upgrades, smart appliances, managed vehicle charging, behind-the-meter energy storage and advanced thermal storage technologies, the authors said.

Massachusetts is also rolling out advanced metering infrastructure, which should help enable incentives for demand flexibility for residential ratepayers and help lower peak load.

Notably, the study’s cost comparisons did not include costs associated with demand flexibility or other demand response resources.

The clean energy pathway assumed a cost-optimized mix of offshore and onshore wind and batteries with storage durations ranging from two to 100 hours. Storage was the largest component of the clean peak portfolio, with 100-hour storage comprising most of the storage built by the model. The model also assumed 4.4 GW of offshore wind and 2 GW of onshore wind.

“While onshore wind is less expensive to build, onshore wind capacity was capped at 2 GW to reflect the constraints of siting onshore wind,” the authors noted.

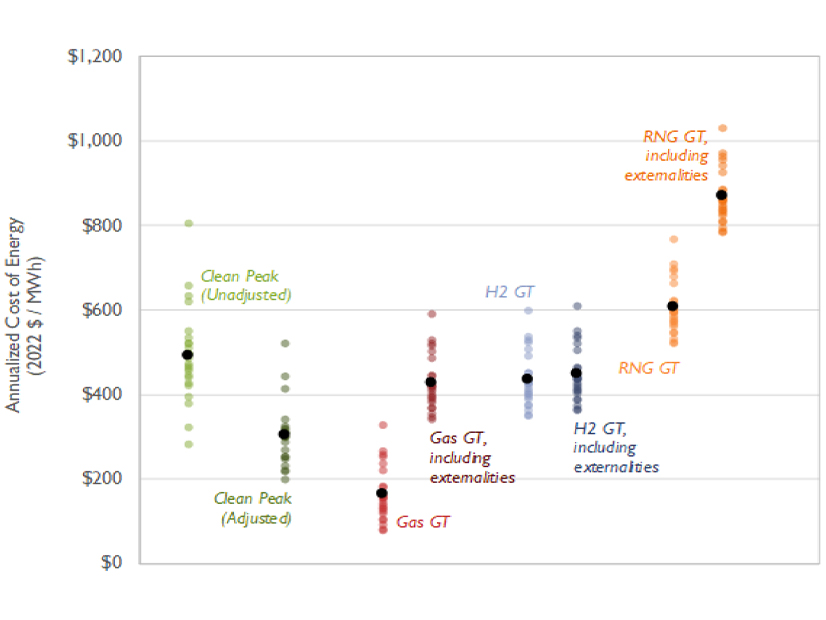

Synapse compared the annualized cost of energy of the clean energy pathway to portfolios composed of new gas turbines and generation fueled by hydrogen and “renewable” natural gas.

When adjusted for the value provided by off-peak wind generation, the findings show the decarbonized pathway to be cheaper than the alternative fuel pathways but more expensive than the gas-based pathway. However, when accounting for “externalities” like carbon emissions and public health impacts the modeling showed the clean portfolio to be the most cost effective.

The report found that the adjusted costs of the clean portfolio would add about $10 per month to the average residential electric bill.

“While these efforts may result in moderate cost increases for ratepayers, the costs need to be considered within the context of the high social and environmental costs of continuing to depend on polluting gas and oil power plants,” the authors wrote.

Recommendations

Based on Synapse’s findings, the authors provided a suite of recommendations aimed at promoting clean peaking resources. These include expanding demand flexibility programs and incentives; prioritizing medium- and long-duration storage; and accounting for public health and climate costs when calculating cost effectiveness.

They expressed skepticism about the potential of alternative fuels to meet peaking demand, pointing to high cost projections and arguing that “replacing fossil fuel use with these alternative fuels won’t meaningfully decrease greenhouse gas emissions and will often maintain the same, or worse, levels of local air pollution.”

The report coincides with intense policy debates in the state over how to define and address issues of energy affordability.

Democratic leaders in the Massachusetts House of Representatives have been working to advance a controversial energy bill that would scale back several key climate programs in the state, particularly its energy efficiency program.

In contrast to the report authors’ emphasis on accounting for the full range of climate effects, the initial version of the House bill proposes to eliminate requirements for the state Department of Public Utilities, including emissions costs when calculating cost effectiveness. The bill would also prohibit state agencies from implementing any regulations or programs with “unreasonable adverse impacts” on energy costs or the state’s economic competitiveness. (See Top Mass. House Members Seeking Major Rollback of Climate Laws.)