Utility securitizations, once used to reimburse power companies for assets that became stranded under electricity market deregulation, are making a comeback. Utilities and state governments are using the ratepayer-backed bonds to deal with the huge costs associated with green energy transition, climate change and even the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Utility securitizations are set for a resurgence as electric utilities deal with costs surrounding the transition out of hydrocarbons into green energy,” said Joseph Fichera, CEO of utility securitization advisory expert Saber Partners. “There are also attempts being made to apply the ratepayer securitization model to costs from the COVID epidemic, as well as the increasing costs associated with climate change.”

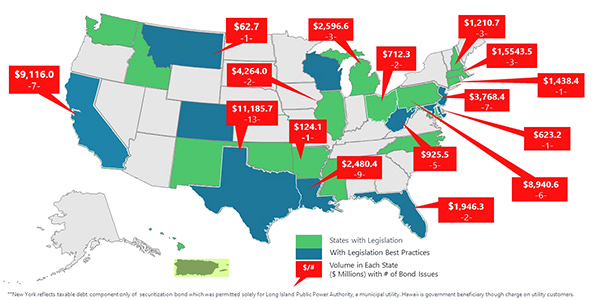

Saber Partners’ forward calendar for ratepayer bond issuance lists five states — California, North Carolina, Wisconsin, New Mexico and Michigan — that have legislation in place for utility securitizations. Utilities in these states are expected to issue as much as $24 billion of ratepayer bonds in the near future.

Colorado and Montana have also recently passed utility securitization enabling legislation. In addition, six states — Kansas, Missouri, Minnesota, Iowa, South Carolina and Arizona — are considering new utility securitization authorizations.

To give an idea of the extent of the resurgence, only $51.1 billion of ratepayer bonds were issued 1997 through 2019, with just $4.1 billion in principal currently outstanding, according to Saber Partners.

“If securitization were used for early retirement of all coal plants in the nation, as well as to pay for COVID costs, perhaps hundreds of billions of dollars in ratepayer bonds would need to be issued,” Fichera said. “Not all coal plants and COVID costs will be dealt with using securitization. Ratepayer issuance going forward, however, very well could surpass the $50.8 billion issued from 1997 through 2019.”

California: $12B+

California’s three investor-owned utilities are seeking to issue more than $12 billion in bonds.

After a long absence from the ratepayer bond market, Southern California Edison in mid-February issued $338 million of ratepayer bonds designed to mitigate future damage from wildfires. Over the last three years, California has seen an unprecedented series of wildfires — fires that some, including California Gov. Gavin Newsom, have attributed to climate change.

Legislators in Sacramento have approved unprecedented levels of utility securitizations, Saber Partners says. SoCal Edison’s February ratepayer issue is likely to be the first in a series of ratepayer bonds as the utility has been authorized to issue up to $1.6 billion worth.

Troubled Pacific Gas and Electric has authorization to issue $3.2 billion for wildfire mitigation costs and is seeking another $7.5 billion of ratepayer bonds to pay wildfire victims, Saber Partners said.

California consumer advocates are vigorously litigating the 7.5 billion securitization authorization, claiming the interests of ratepayers aren’t being adequately considered, though PG&E has promised that securitization deals will be neutral with respect to overall electricity rates for consumers.

“If utility securitizations are to be done on a best practices basis, the interests of consumers must be of paramount importance,” Fichera said. “Ideally that means consumers must be represented in the negotiations where the structure of securitizations are laid out.”

Last June, Saber Partners was retained by the Public Staff of the North Carolina Utility Commission to advise on Duke Energy’s $1 billion proposed securitization to pay for storm damage. In total, Saber Partners has advised on more than $9 billion of utility securitizations, mostly retained by utility regulators who wanted guidance on protecting consumers.

Funding Deregulation

Utility securitizations saw their genesis during the electric utility deregulation movement of the late 1990s. Vertically integrated utilities in many states were required to separate transmission, which remained regulated, from power generation, which was opened to competition.

The idea was to promote efficiency by allowing unregulated generating companies to compete with each other to offer electricity at lower prices to win market share.

Importantly, electric industry reformers also wanted market price signals to start determining when and in what form new generation assets would be built or disposed of — unlike the centralized, command and control under the utility industry model that prevailed for more than 100 years.

But splitting transmission and generation created some headaches, not the least of which was the fact that many generation assets had yet to be fully paid for in the utility customer rate base. As a result of deregulation, generation assets were held in unregulated entities that had zero ability to amortize costs through a normally captive customer base.

These generation assets became known as “stranded assets,” a term that is now in ubiquitous usage in the electric power industry. Among the stranded assets were generators such as Philadelphia Electric Co.’s Limerick nuclear plant, which produced power at a cost that was no longer competitive in the deregulated environment.

Enter utility securitization. Ratepayer-backed bonds were used to refinance utility holding company balance sheet debt, as well as to pay back equity associated with the investments in the newly stranded assets.

By going to state utility boards and through special legislation, electric utility holding companies were given permission to float these new ratepayer bonds to get reimbursed and spread the costs to ratepayers over time at a lower cost of funds. This idea then spread to massive storm damage costs, starting with Hurricane Katrina and Rita in 2005, and for rising environmental costs. PG&E and other California utilities are planning to use ratepayer bonds to reimburse COVID related costs, according to Saber Partners.

In a ratepayer bond deal, a special purpose vehicle (SPV) — a trust, basically — is set up that holds an irrevocable claim to a new charge on customer bills, a charge specifically levied to reimburse for any utility costs approved by state legislators. Regulators monitor the SPV trust and every six months adjust the special charge to ensure that there is enough money in the SPV to pay off the ratepayer bond on time.

Enthusiastic Reception

Credit rating agencies have given ratepayer bonds AAA ratings based mostly on the irrevocability of the claim to the cash flow from the special charge. Another credit positive is the fact that regulators periodically adjust the level of the special charge to ensure adequate funding of the trust.

Judging by the enthusiastic reception investors gave So Cal Edison’s $338 million transaction in February, there should be no problem selling upcoming utility securitizations. The offering was eight to 10 times oversubscribed, sources say.

Utility securitizations have brought together interest groups that have traditionally been adversarial.

“Environmental groups and renewable energy advocates have joined utilities in pushing for securitizations,” said J. Paul Forrester, partner at Chicago-based law firm Mayer Brown. “It’s not often that you see utilities and environmentalists working hand-in-hand, but it makes sense because utility securitizations will smooth and accelerate the path for power company green energy transition.”

In 2019, the Sierra Club threw its weight behind utility securitizations. “Securitization is a key financing tool that can help electric utilities accelerate the retirement of uneconomic, polluting coal plants and move more quickly toward a grid powered by clean, safe renewable energy,” the group said in announcing a report on the subject.

While utility securitizations will lower overall costs for dealing with stranded coal assets and climate change costs, the extremely complex nature of the deals means that the costs of structuring securitized utility transactions are very high.

Saber Partners said that some deals have had structuring costs north of $20 million, costs that Forrester is working to mitigate.

While he would not name his client because of confidentiality concerns, Forrester says he has been retained by a nonprofit to build a utility securitization deal template — a kind of “plug and play” solution — that utilities and state governments can use to allow for more securitizations while also reducing costs considerably.