New York’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2015 were virtually unchanged from 1990 levels, according to a newly published study that highlights upstream impacts and the role of methane under the state’s revised reporting rules.

The study, published in the Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences, concludes that methane emissions have grown as carbon dioxide emissions have declined, leaving New York’s total GHG emissions in 2015 virtually unchanged from 1990.

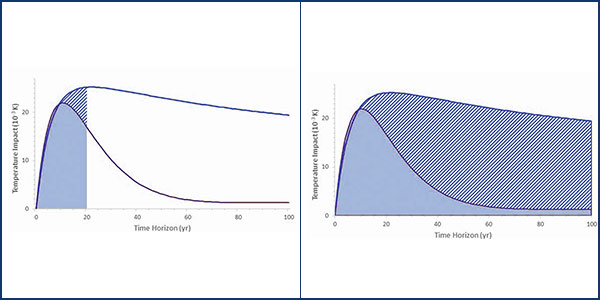

The analysis by Robert Howarth, Cornell University professor of ecology and environmental biology, was based on the new emissions reporting rules enacted in the 2019 Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (A8429), which calls for reporting to include emissions from outside New York if they are associated with energy use within the state. It also requires that methane emissions be compared with CO2 over a 20-year time frame rather than the 100-year time frame still used by virtually all other governments in the world, according to Howarth. Methane is about 80 times as potent at trapping heat as CO2 in the first 20 years but has a much shorter half-life.

Calculating Emissions

Howarth’s paper compares emissions based on the CLCPA approach for GHG reporting with the traditional inventory, driven almost entirely by CO2 emissions. As of 2015, the latest state data available for comparison, carbon emissions had declined by 15% since 1990, thanks to an 88% cut in coal consumption and a 27% decrease in petroleum use, he said, while methane emissions increased by almost 30% over the same period, largely from the increased consumption of natural gas. According to the new GHG reporting rules, methane rose from 28% of all fossil-fuel emissions in 1990 to 37% in 2015. (Other GHGs, including nitrous oxide and fluorocarbons, represent less than 4% of total emissions.)

“A robust conclusion is that total emissions have changed remarkably little over the past 25 years, when viewed through the lens of the CLCPA approach,” Howarth wrote.

It is difficult to establish the 1990 baseline greenhouse gas emissions, which the state needs to finalize by December 2020, Howarth said. Next year, the state agencies will determine how to account for contemporary GHG emissions, he said.

“I would prefer they be done together in a combined way … but I think overall, [the state agencies] have done a pretty good job,” Howarth, one of 22 members on the state’s Climate Action Council, told RTO Insider.

The CLCPA’s mandate means “not simply to rely on EPA-packaged emissions estimates, but rather to fall back and use the best available science, including the peer-reviewed academic science,” Howarth said. “They’re not using EPA estimates at all, which is good, because the EPA has systematically low-balled [emissions], particularly methane emissions from the oil and gas industry, for decades and continues to do so. And the peer-reviewed literature is full of papers where that’s been demonstrated time and time again.”

New York state agencies did not do a thorough review of the peer-reviewed literature and are relying on the Greek model, a method developed in Europe for estimating GHG emissions, which doesn’t reflect all the latest and best science, Howarth said. “I would have preferred the DEC [Department of Environmental Conservation] make sure they have the best science in there, but nevertheless, it’s a step in the right direction.”

Including out-of-state emissions in reporting “is a big step forward,” he said, because most methane emissions occur at the site of gas production, processing and storage. “When we use natural gas here in New York, a lot of those methane emissions are occurring in Pennsylvania, West Virginia [and] Ohio, and we should take responsibility for them. The DEC in their draft has included that, but they’ve come up with an estimate of methane that I think is low. It’s not as low as what the EPA would have you believe, but it’s still somewhat low,” Howarth said.

On the other hand, the DEC also included CO2 emissions from out of state that are associated with the mining, processing and transporting of the fuel, whether coal, oil or gas, he said.

“And they came up with a pretty big number for that. I sidestepped that in my paper and said you might want to do it, but I thought it was a pretty big challenge — beyond what I was going to take on,” Howarth said.

Last month, New York officials on the Climate Action Council discussed the DEC’s newly proposed statewide GHG limits of 60% of 1990 emissions by 2030 and 15% by 2050. Administrative Law Judge Molly McBride will conduct two public comment hearing webinars for the proposed rule on Oct. 20, and public comments will be accepted by the DEC until Oct. 27. (See NY Seeks Comment on Proposed Emissions Limits.)

Meeting the CLCPA’s 2030 emissions target will require major reductions in natural gas use in the residential and commercial sector and similar cuts in petroleum use in transportation, Horwath said. “To date, the state has focused little attention on GHG emissions from these sectors and has instead prioritized reducing the use of fossil fuels to produce electricity.”

Converting from natural gas heating to modern heat pumps will reduce GHG emissions even if the heat pump is powered by electricity generated from fossil fuels, Howarth said. “Similarly, electric vehicles reduce overall emissions compared to gasoline- and diesel-powered vehicles, even if fossil fuels are used to produce the electricity, because of the greater efficiency of the electric vehicles. Consequently, to reduce overall GHG emissions for New York state, electrification of heating and transportation systems must proceed as quickly as possible, even if this precedes reduction of fossil fuels to produce electricity.”