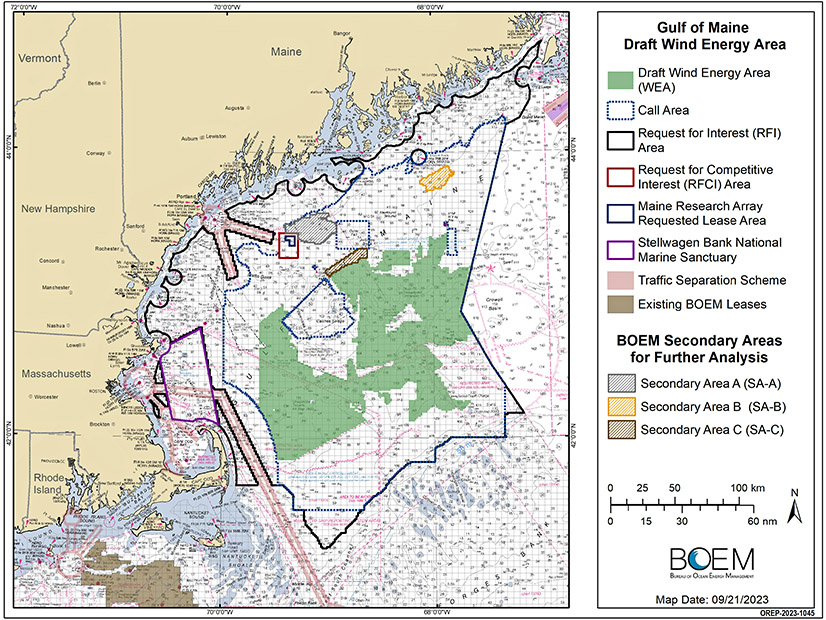

Federal regulators have designated a draft wind energy area in the Gulf of Maine, shrinking it substantially from its earlier stages and excluding a key lobster fishing area.

Federal regulators have designated a draft wind energy area in the Gulf of Maine, shrinking it substantially from its earlier stages and excluding a key lobster fishing area.

The 3.52-million-acre zone has a potential capacity estimated at more than 40 GW. It stretches as much as 120 miles off the New England coastline, and ranges across water too deep for wind turbines with fixed-bottom foundations.

The buildout instead will require floating turbines, which still are being developed and improved. They have begun to be installed only recently, three decades after the first fixed-bottom offshore wind farm was built off the coast of Denmark.

In announcing the draft wind energy area on Oct. 19, the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management touched on the newness of the floating wind sector, saying the Gulf of Maine presented an opportunity for the United States to take a leadership role.

The state of Maine hopes to do exactly that, and for years has been priming itself to reap the expected environmental benefits of floating wind and the economic benefits of leading its buildout.

The state has set a goal of 3 GW of offshore wind by 2040. The state university has been steadily researching designs; it floated a scaled-down turbine close to shore a decade ago.

BOEM is processing the state’s request for a research lease that would allow it to place up to 12 floating turbines rated at up to 144 MW in a 9,700-acre area of the gulf.

The trade group Business Network for Offshore Wind welcomed BOEM’s announcement. In a prepared statement, Vice President John Begala said: “Advancing leasing in the Gulf of Maine sustains that confidence and unlocks new investment in the U.S. floating offshore wind supply chain, giving our nation the opportunity to catch up with the global market in this emerging field. Floating offshore wind is also crucial to New England states, whose demand for new, clean power generation is predicted to grow from current levels as they move to decarbonize their economies.”

President Biden has set a national target of 30 GW of offshore wind by 2030 but lowered the goalpost for floating wind: only 15 GW, and not until 2035.

The extra time will allow for further research and development to address the technical challenges of floating wind.

The world’s deepest fixed-bottom wind farm stands in not quite 200 feet of water off the Scottish coast. In the Gulf of Maine, the area with the greatest wind energy potential is 600 to 800 feet deep.

The longer time frame also should allow the U.S. offshore wind industry time to overcome the financial and logistical problems it is struggling with.

Many of the fixed-bottom projects contracted but not yet under construction off the Northeast coast have run into major headwinds. Three are in limbo after reaching deals to cancel their power purchase agreements, and developers of others are threatening to pause or cancel their projects unless they get more money.

However, policymakers, the offshore wind industry and its advocates continue to mark achievements amid the struggles. They expect the need for clean power to smooth out the growing pains offshore wind is experiencing.

The Business Network for Offshore Wind presented both sides of the ledger in its third-quarter report, issued Oct. 17.

BOEM Director Elizabeth Klein said in a news release that public comment and stakeholder concerns were incorporated into the draft wind energy area. The boundaries do not include Lobster Management Area 1 or North Atlantic Right Whale restricted areas, for example, and there is a six-mile buffer around important groundfish areas. BOEM also said it tried to avoid a majority of historic and present fishing grounds of Tribal Nations.

Gov. Janet Mills (D) and the state’s congressional delegation earlier this year urged these considerations. In a prepared statement Oct. 20, Mills said: “We look forward to reviewing the proposal in detail, but we are encouraged that the Bureau has initially listened to our concerns and those of the fishing community by excluding Lobster Management Area 1 in its draft.”

At an earlier stage of the process, BOEM’s draft call area had spanned 9.9 million acres and included Lobster Management Area 1.

Advocates for the fishing industry, the environment and labor hailed the removal.

“This is how the process is supposed to work,” Virginia Olsen, Executive Liaison of Maine Lobstering Union Local 207 said in a news release. “The federal government listened to the concerns of our fishing communities, and now they are sending a strong signal that an offshore wind industry that fundamentally harms the hardworking Mainers making their living on the water is neither in line with Maine’s values nor welcome in the Gulf of Maine.”

Publication of the Gulf of Maine Draft Wind Energy Area launched a 30-day public comment period.

Additional adjustments are expected to be made based on input received, BOEM said.