As it updates its energy plan to reflect new challenges to decarbonization, New York is contemplating what until recently seemed improbable, or even unthinkable: new fossil-fired generation.

The state Energy Planning Board voted July 23 to publish the draft 2025 update of the state Energy Plan after 10 months of deliberations. A series of hearings across the state is scheduled to gather input on the draft.

Further updates and revisions to the draft are expected as it approaches finalization toward the end of this year and the effects of federal policy changes become clear.

The board’s chair — Doreen Harris, CEO of the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority — told RTO Insider that the huge shifts in federal policy over the past six months created uncertainty to a degree that required the board to present a range of scenarios in the draft. She said federal actions over just the past few weeks may have rendered some of those scenarios overly optimistic.

The Trump administration is actively moving to thwart energy efficiency and clean energy initiatives such as those New York has worked more than a decade to build. Meanwhile, the recently enacted reconciliation bill, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, eliminates federal subsidies that states were counting on to incentivize renewables development and shifts billions of dollars in federal spending obligations to state governments, thus limiting whatever inclination states had to subsidize renewables on their own.

As such, New York is contemplating strategy shifts on multiple fronts with the draft update.

Ambition vs. Results

New York has had mixed results in expanding its renewables portfolio and shrinking its carbon footprint.

The Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act — New York’s landmark 2019 climate law — mandates 70% renewable energy and a 40% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, as well as 100% zero-emission energy by 2040.

But officials have acknowledged the state is likely to miss the two 2030 goals, possibly by a wide margin: GHG emissions were down only 9.3% as of 2022, and renewables accounted for only 27% in 2023.

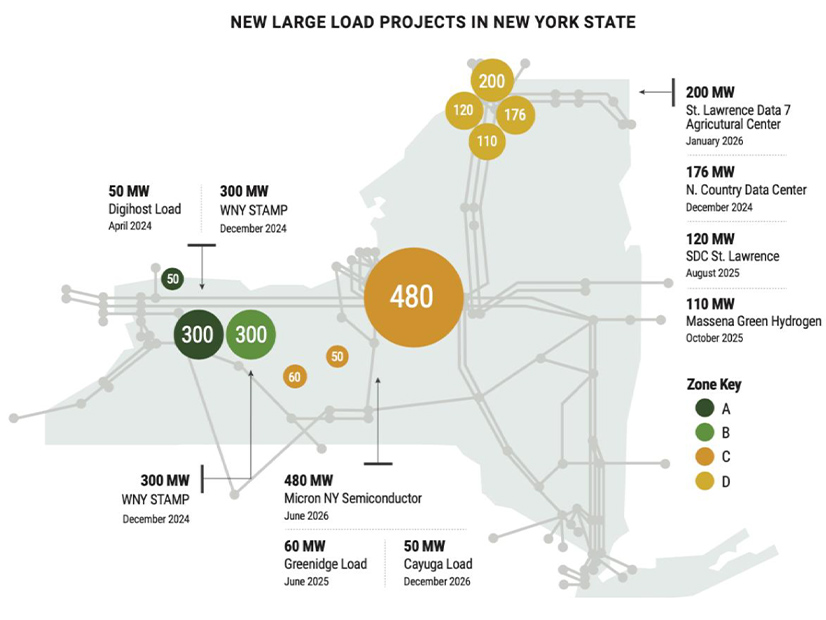

The draft update acknowledges the challenges facing the 2040 zero-emissions energy goal as well. Given the 23% increase in peak demand and 26% increase in annual demand expected by 2040, the draft emphasizes the importance of not falling further behind on generation capacity.

One scenario envisions current-day nuclear and hydro assets continuing to play a key role in the state grid in 2040, joined by 35 GW of solar; 9 GW each of storage, onshore wind and offshore wind; and 16 GW of green hydrogen combustion.

Any of those targets could be a challenge in the current environment, but hydrogen stands out as a leap of faith.

The draft immediately acknowledges the technical challenges of generating huge quantities of hydrogen in an ecologically and economically sound manner. And it acknowledges that hydrogen or other “clean firm” technologies critical to this planning process are not yet scalable.

So the draft looks at fossil fuel as indispensable for some time to come. Natural gas and petroleum will be diminished but still important energy resources in New York in 2040, the draft says, and fossil generation will remain essential to grid reliability.

But a quarter of the state’s combustion generation capacity will be at retirement age as soon as 2028, so the state will need to be strategic about the pace of combustion unit retirements, the draft warns, and will need to consider whether new or repowered fossil-fuel generation is necessary.

Harris said the state’s energy planning process has been faced with moving variables since President Donald Trump began his second term, and she said some of the scenarios laid out in the draft plan are based on factors and assumptions that recently became outdated.

“If anything, the reconciliation bill may have rendered even that planning case a bit optimistic from the perspective of renewable deployment in particular,” she said.

NYSERDA’s senior vice president for policy, analysis and research, Carl Mas, said the language in the draft about new fossil generation is intentionally broad because there is such a broad range of possible outcomes as New York navigates state and federal economic and policy factors.

But there are scenarios under which the state — which had sought to phase out fossil fuel generation in the 2030s —would instead seek construction of new fossil generation or retrofits to make older facilities cleaner and more efficient.

“With the load growth that we’re seeing, we feel like we have to remain flexible,” Mas said. “There’s extreme amounts of uncertainty, but we have a very old fleet, and we have a growing load and substantial new headwinds that we didn’t have five or six years ago.”

This does not alter the state’s commitment to renewables and decarbonization, Harris and Mas said. It recognizes that the plan for carrying out that commitment may need to be modified to maintain reliability.

Tough Decisions

New York has a number of hard choices to make with its energy portfolio, and the draft update of the plan lays out some of the potential decision-making pathways in a rapidly evolving landscape. But it will not make the decisions easier.

Renewables advocates have been unhappy about the state ratcheting back initiatives that have become untenable or expensive, and about the slow pace at which the New York Power Authority is starting its role as a renewables developer. Any move to authorize major new fossil infrastructure is likely to go over just as badly.

Meanwhile, New York must decide whether to continue to subsidize the nuclear power plants that supply 22% of the state’s total electricity and 42% of its emissions-free electricity. Over the past seven fiscal years, this zero-emission credit program has consumed $3.73 billion gathered from surcharges on electric bills.

The draft plan highlights the importance of the ZEC program, but it also states bluntly that “it is not feasible to continue increasing the number and scale of programs that electric ratepayers need to fund.”

Another challenge: New York’s renewable energy pipeline — partly rebuilt after mass cancellations in 2023 — faces a new round of cancellations because of the impending end of federal tax credits under the reconciliation bill.

“We have literally seen the federal government’s action result in tens of billions of dollars of impact on New Yorkers with respect to clean energy deployment costs,” Harris said.

There is a wave of collateral damage beyond the tax credits, she said, as the industries and workforce that were growing in the clean energy sector retract and retreat.

Harris added, though, that renewable energy is not expected to halt; the question is how much it will slow.

“So this energy plan is taking into account the realities of having those tools impacted,” Harris said.

Simultaneous Goals

The draft plan’s summary alone stretches 80 pages and reminds the reader why governmental processes sometimes move so slowly: It is filled with parallel and secondary goals that rope in a massive cast of stakeholders and competing interests.

The draft suggests that as New York is reducing its carbon footprint and keeping its grid reliable, it should upgrade one of the oldest housing stocks in the U.S.; move to 100% zero-emission vehicle sales; reduce negative impacts on disadvantaged communities and actively steer positive impacts toward them; bolster organized labor; help poorer New Yorkers cut their energy costs; craft a more cohesive energy planning process; support research and development; build at least 1 GW of nuclear capacity; develop the energy workforce; lead the country in battery energy storage safety; maintain reliable gas transmission networks that can meet peak demand; consider wholesale electricity market reforms; and integrate renewables into the land-planning practices of often oppositional local governments.

And it wants to do all of this affordably.

“These are all goals that the state can meet without sacrificing one for another,” the draft says.

It estimates that some of the scenarios would raise energy costs more than 35% by 2040. That is expected to be offset to some extent by lower health care costs and other societal benefits, but it would be a lot of money on top of already high rates. Heavy investment is needed under any scenario because of the age of existing transmission and generation infrastructure and the increased demands expected to be placed on them.

But any embrace of new or rebuilt natural gas-fired generation would be a bitter pill to swallow for clean energy advocates.

Marguerite Wells, executive director of the Alliance for Clean Energy New York, avoided the words “natural gas” in a statement but made the trade group’s priority clear: “Electric demand is rising, and legacy generating sources are aging. It’s patently obvious that renewable sources are going to be the fastest and lowest-cost method of bringing new power onto the grid.”

ACE NY looks forward to commenting on the draft, she said, and working with the state to identify the inefficiencies and road blocks that are delaying renewables.

State policy not long ago favored natural gas as the preferred alternative to coal and oil.

The 2015 update of the State Energy Plan discussed New York’s ambitions for, and early steps with, renewables. But it also said, “Economic, operational and environmental advantages make natural gas the current fuel of choice for new and replacement generation in New York.”

The 2019 climate law canceled that line of thought. But there was always going to be an off-ramp in case the vision did not come together as hoped.

In the 2022 Scoping Plan it prepared for the law, the state Climate Action Council said, “The effectiveness of programs and policies should be continually evaluated and changed if renewable energy is not being deployed at the pace necessary to achieve the requirements on time.”

The July 23 vote to publish the draft set in advance the process for such a potential change.

Jackie Bray, commissioner of the Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Services and a member of the Energy Planning Board, said she was glad alternate scenarios were included in the draft in case the preferred scenario becomes impossible.

There can be a tendency in this type of planning process, she said, for well-meaning leaders to continually add objectives to a blueprint on the assumption that there is time over the next decade to figure out how to reach those objectives.

“Make sure that we are being realistic about what we can deliver and what we must deliver,” Bray urged listeners.