New Jersey faces tough decisions on how to balance the risk of blackouts against the cost of reducing their frequency, speakers said at a resource adequacy forum organized by the state Board of Public Utilities.

Any plan to combat the expected surge in demand from data centers, they said, likely will be fraught with uncertainty because the emerging situation is unprecedented.

Possible strategies mentioned at the Aug. 5 forum include asking data centers to curb their use at high-demand moments, enhancing energy efficiency strategies, going outside of PJM for power and better coordinating distributed energy resources and storage.

In each case, a proper allocation of costs and a benefit-cost analysis will be critical, speakers said at the forum, conducted at The College of New Jersey in Ewing, N.J. The challenge is multiplied by the sheer size of the problem.

“The loads are very difficult to plan for, and they appear very, very quickly,” said Tim Gallagher, CEO of ReliabilityFirst. “These things bring very unique and significant challenges to both the planning and the operation of the bulk power system.”

Higher Prices Needed

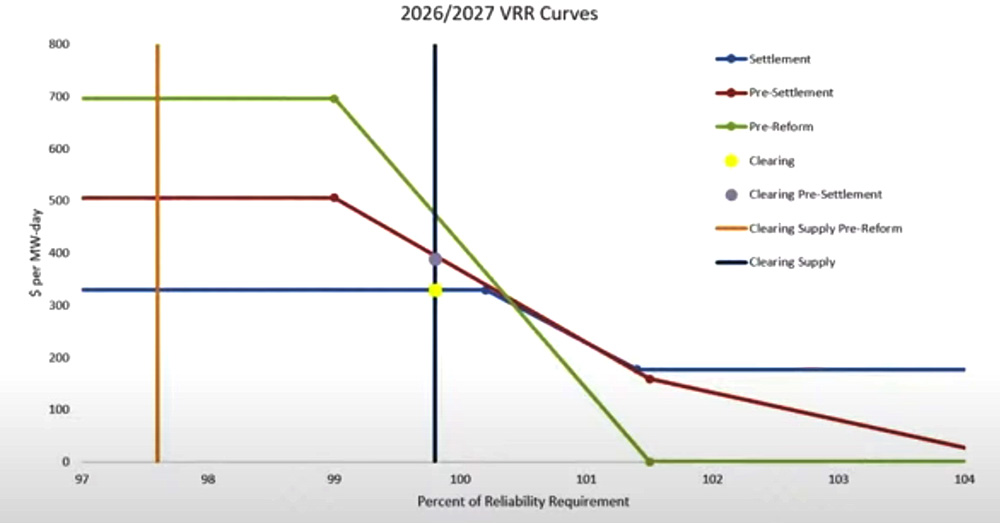

The conference came two weeks after PJM revealed that prices at its July capacity auction soared to $329.17/MW-day (UCAP) RTO-wide for delivery year 2026/27. Prices in the 2024 auction jumped to $269.92/MW-day, the result of load growth, generation deactivations and changes to risk modeling that shrank reserve margins. (See PJM Capacity Prices Hit $329/MW-day Price Cap.)

While New Jersey officials have voiced outrage at the auction prices, and a 20% hike in the average electricity bill, the prices still don’t stimulate new generation development, warned Richard Levitan, president of Levitan and Associates, an energy management consulting firm.

“We have to be realistic about clearing prices continuing to ascend in order to get price signals to developers for new build,” he said. “We could be looking at price signals that are much, much higher, closer to $700 per MW-day.”

Acceptable Power Loss Level

Paul Youchak, of the BPU’s office of federal and regional policy, said PJM sets its reliability levels at the commonly held standard of “1-in-10,” meaning only one event every 10 years in which the RTO could not meet demand for at least 24 hours.

States that want to lower that risk can invest more in new generation, pushing up costs, he said. He questioned whether “reliability and affordability today … are diverging in a way that hasn’t diverged before?”

Gallagher explained that at present, “ratepayers emphasize costs more than reliability,” in large part because “we’ve enjoyed 99.9% reliability for most of our lives.” If the state continues on the current path as demand rises, “reliability starts to suffer,” he said.

That may trigger calls for a new standard, he said, adding that NERC is moving toward a new standard of “energy adequacy, which is actually studying every hour of the year to make sure you have enough electricity for every one of those hours.”

Unified Load Forecast

Whatever standard is in place, the state faces a difficult challenge predicting future load.

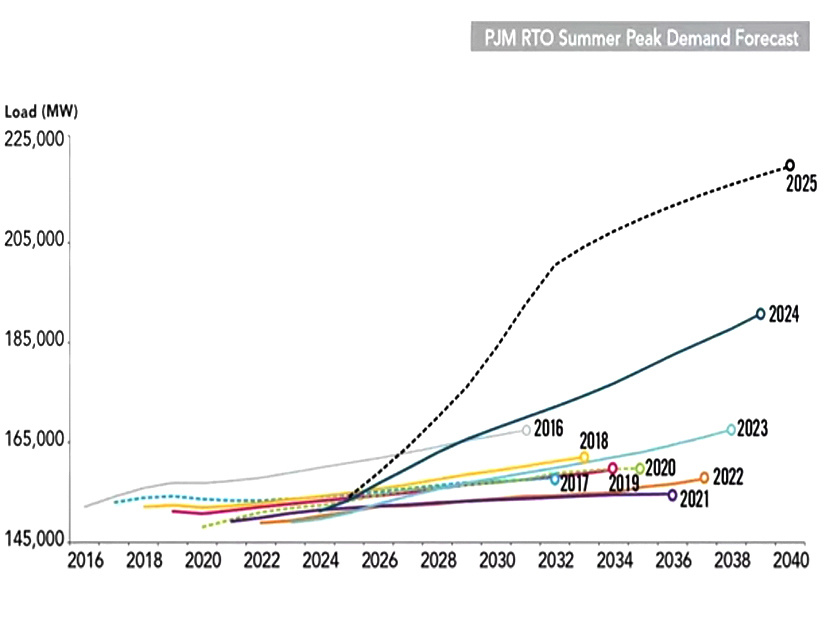

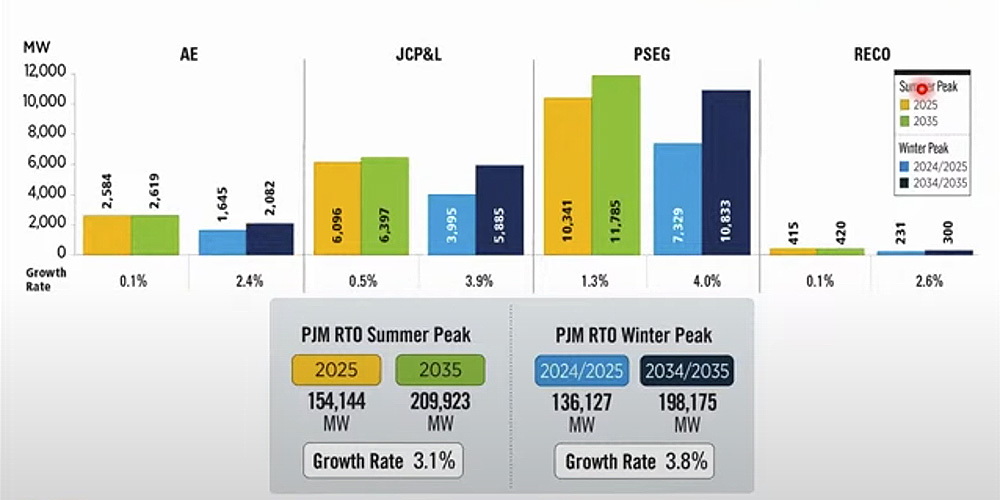

Youchak emphasized how suddenly the demand picture has changed. In 2023, he said, PJM predicted that by 2038 the region would have load of about 165,000 MW. By 2025, the RTO predicted the 2038 load would be around 220,000 MW, an increase of more than one-third.

“It is an order of magnitude difference from the type of volatility we’ve seen in the past,” Youchak said.

New Jersey, with 100 data centers at present, ranks only 15th in the nation, Gallagher said. And they typically aren’t the kind of heavy-load artificial intelligence facilities that present the biggest challenges, he said. Instead, New Jersey data centers work to “support government services, public health systems, emergency and disaster response” and other functions, he said.

But because New Jersey is an energy importer, it will be impacted by the arrival of big data centers elsewhere in the RTO region, and “must plan for this rise in demand,” said Margarita Patria, a principal of Charles River Associates.

“What’s needed is a clear understanding of data center load trajectory going forward,” she said. “We need a unified approach in assessing data central load and move to perhaps probability-based forecasting tools that more accurately reflect the state of affairs and will enable more informed decision making.”

Yet the unique element of hyperscalers, the largest data centers, makes that difficult, said Tom Rutigliano, senior climate advocate for Natural Resources Defense Council.

Traditional statistical methods of basing predictions on past performance have difficulty accounting for the dramatic influx of data sector loads that have no precedent, he and other speakers said. And forecasts may include data center projects that may never come to fruition, speakers said.

Andrew Gledhill, senior analyst for resource adequacy planning at PJM, said the organization is working on “implementation guidelines, talking about the key criteria” that should be included in forecasts, such as “the uncertainty of data center development when you start looking at five to 10 years.”

One way to address that is to produce “accuracy metrics on these projections,” including after-the-fact scrutiny of data center forecasts to determine “what came to fruition, how did the numbers match up with what they were expecting at the time?” Gledhill said.

The shifting demand profile of the region has added to the importance of getting the forecasts correct. Part of the challenge is that the highest peaks are now in the winter. A loss of power can plunge residents into darkness and cold and create much more severe consequences than in the past, when summer peaks dominated and the main impact was loss of air conditioning.

“If we don’t have electricity for a sufficient period of time today, people actually die,” Gallagher said, citing the dozens of deaths that occurred during power loss triggered by the severe winter storm in December 2022.

In addition, peaks triggered by data centers are more sustained, and so more challenging to handle than the relatively brief demand surges resulting from a cold spell or a heat wave, Gledhill said. Of the 32 GW of demand increase expected in the PJM region by 2030, 30 GW will come from data centers, he said.

“That’s generally flat load,” he said. “So the load profile, as we move into time, is getting flatter and flatter, which means that there’s going to be more hours of risk that pop up.”

Managing Demand

Sam Newell, principal with the Brattle Group, said the state should “foster energy efficiency demand response programs,” essentially asking users at a “mass market level” to reduce their load at peak times. The state, for example, can set up virtual power plants to manage a network of distributed energy resources, such as solar panels, batteries and electric vehicles, to handle load at peak moments.

Speakers also suggested that big energy users be asked to cut energy use when the overall load gets heavy. But big data centers are reluctant to take that step, in part because “it’s difficult for them to predict when an AI-related data center is going to go into learning mode, and that’s when their electric demand ramps up significantly,” he said.

In addition, Newell said, “a lot of the data centers are not hyperscalers. But they might have 400 to 600 tenants in the data center, and it’s difficult for them to pick exactly which ones of those tenants” should take part in demand-response load cuts, he said.

One audience member asked if New Jersey should continue the current level of subsidies for solar when the availability factor — the percentage of its full name plate capacity that it can generate electricity — for solar is only about 11%, due to the limited time in which panels generate electricity. In contrast, PJM rates a nuclear generator at 93%, offshore wind at 69% and a gas combustion turbine at 60%.

Rutigliano said the benefit of solar is it’s cheap and clean. But he acknowledged that “it doesn’t give you a lot of reliability value.”

“I’ll confess, NRDC’s modeling says that the most cost-effective way to a low-carbon grid is a fossil fleet that’s around the same size as what we have now; it just doesn’t run very often,” he said. “Since the reliability or research adequacy issue is the clear and present one, subsidies now in PJM should be flowing to storage, to wind. Offshore wind actually brings more value than a combustion turbine.”