By Michelle Bloodworth

More and more, energy policy analysis seems to be based on finding a preferred answer rather than a realistic answer. Case in point, a recent Grid Strategies report, sponsored by several environmental organizations, claims that Department of Energy (DOE) emergency orders to temporarily keep fossil power plants from retiring could cost either $3 billion or $6 billion annually by 2028.

Each estimate is based on a different assumption about how many fossil fuel power plants might retire over the next three years. For perspective, these costs, even if correct, would represent either 0.6 or 1.2% of annual consumer expenditures for electricity, which total about $500 billion. (According to EIA, end use electricity expenditures totaled $488 billion in 2023, which is the most recent data.)

The Secretary of Energy has the legal authority under Section 202(c) of the Federal Power Act to issue orders to prevent “energy emergencies.” The potential reliability problems NERC has been warning about qualify as an emergency under the Federal Power Act.

Former FERC Chair Mark Christie in July warned that “the reliability threat is not on the future horizon. It is now here.”

One of the primary reasons for these serious warnings is the retirement of fossil power plants. That’s why it has become increasingly important to stop retiring power plants because they are needed for reliability.

From a cost-benefit standpoint, it’s important to consider the benefits of 202(c) orders, which the report ignores. DOE, for example, estimates the annual cost of blackouts to be $150 billion.

Also, an unreliable electricity grid during Winter Storm Uri cost the Texas economy between $80 billion and $130 billion.

As to the possible cost of DOE orders to keep plants running, the report makes a number of questionable assumptions that drive its large cost estimates. One assumption is that all fossil power plants (as many as 90, according to the report) that might retire for one reason or another over the next three years actually will retire.

This seems improbable because fossil power plants will be needed to satisfy load growth driven by data centers, advanced manufacturing, crypto mining and electrification of the economy, and EPA is rewriting rules that were expected to cause the premature retirement of many fossil power plants. In fact, utilities already are changing their minds and, so far, have deferred the retirement of 29,000 MW of coal-fired generation.

Another assumption is that every one of these 90 retiring plants would be directed by DOE to continue operating for a full year. However, we don’t really know how many plants actually would receive 202(c) orders, but we know that DOE’s authority under Section 202(c) has been used sparingly — just 27 times since 2000. Only two of these orders lasted for more than 90 days, so assuming that every retiring plant, regardless of how many there might be, would be directed to operate for one year seems unlikely, if not improbable.

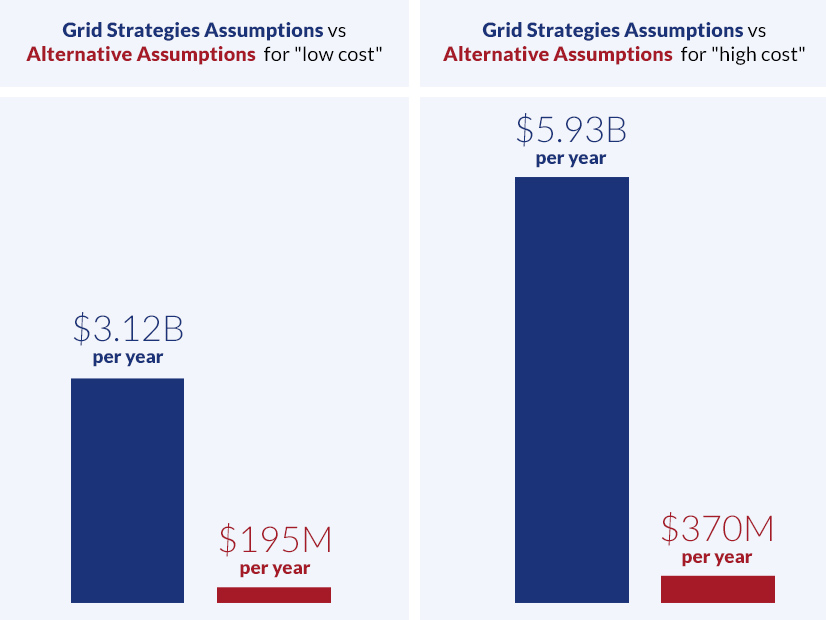

We thought using different assumptions would be an interesting way to test the Grid Strategies cost estimates. So we assumed that fewer retirements would happen (half the number Grid Strategies assumed), that only half of these retirements would receive 202(c) orders and that the orders would direct each of the plants to operate for three months, not a full year.

With these alternative assumptions, the cost estimates are more than an order of magnitude lower. The $3 billion estimate is reduced to a little less than $200 million, and $9 billion is reduced to $370 million.

Obviously, no one knows what will happen by 2028, but suspending plans to retire coal and natural gas power plants is even more critical for grid reliability than issuing temporary 202(c) orders.

Michelle Bloodworth is president and CEO of America’s Power.