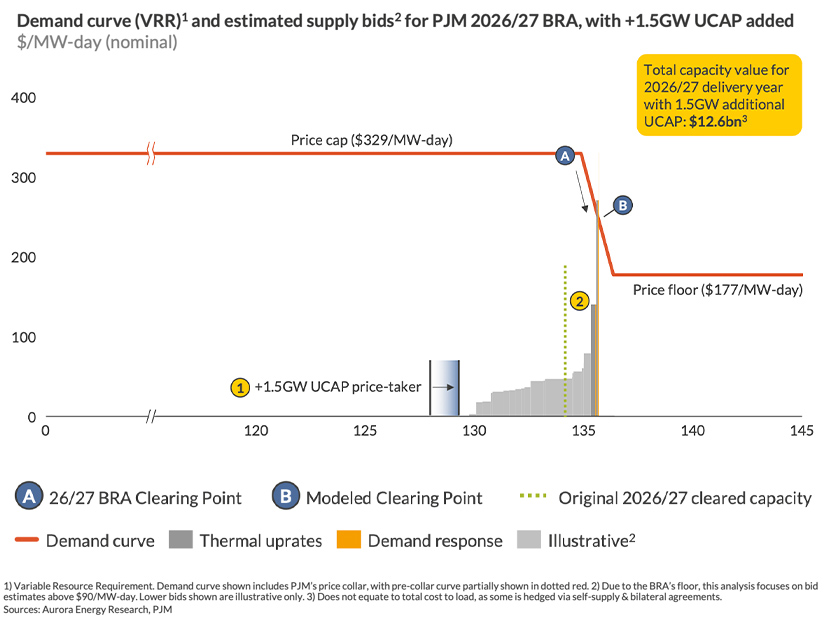

If just 10% of the land-based renewables in PJM’s generator interconnection queue had been developed, the total cost of the RTO’s 2026/27 capacity auction would have been reduced by $3.5 billion, according to an analysis GridLab commissioned by Aurora Energy Research.

If just 10% of the land-based renewables in PJM’s generator interconnection queue had been developed, the total cost of the RTO’s 2026/27 capacity auction would have been reduced by $3.5 billion, according to an analysis GridLab commissioned by Aurora Energy Research.

The queue has 130 GW of nameplate capacity that entered before 2024, and just a fraction of the solar, wind and batteries in it would have cut 2026/27 capacity costs down to $12.6 billion from the $16.1 billion in actual costs.

“I think part of my frustration with the narrative coming out of PJM was they’re sort of blaming state policy for the reason that the auction has gone up so much. They say, ‘State policy is forcing plants to retire,’” GridLab Executive Director Ric O’Connell said in an interview. “And I just don’t think it’s true. I think the reason that the auction has gone up is because PJM basically has taken a very long time — the longest of all the RTOs — to get new capacity online.”

The only state policy actually requiring plants to retire is in Illinois, and that does not kick in for 10 years, O’Connell noted. A lot of retirements have happened in Ohio, which does not have the same stringent clean energy policies as more liberal states, he said.

Renewables have less of a capacity value than their nameplate, but the analysis used the same effective load-carrying capability values as the RTO.

“Wind actually has a really high capacity value because the risk periods are in the winter,” O’Connell said. “And the reason the risk periods in PJM were in the winter is because gas heavily underperformed in Winter Storm Elliott.”

The last time PJM’s grid faced major reliability issues was during that storm in December 2022, and the main culprit was natural gas. (See PJM Recounts Emergency Conditions, Actions in Elliott Report.)

The auction’s high prices signaled that supply and demand conditions in PJM are tight. As demand increases, the reserve margin gets narrower — making the timely connection of new resources increasingly critical to avoid high prices and threats to reliability.

PJM said in a statement that it agrees it needs to remove obstacles for all types of generation resources coming online.

“We are committed to connecting new generation to the grid as quickly as possible,” the RTO said. “PJM has processed about 160 GW of proposed generation resources, mostly renewables or batteries, since 2023. There are about 46 GW of new resources that will be processed by the end of 2026. We are currently working on multiple fronts, including our partnership with Google/Tapestry, to further streamline our processes by leveraging AI.” (See PJM, Alphabet Partnering on AI Tools to Speed Interconnection.)

As of October, about 60 GW of capacity had cleared the queue and either had signed interconnection agreements or were offered such deals, meaning that they should be ready to move forward on construction, PJM said.

But they are not getting built.

Both PJM and the GridLab study point to issues outside the RTO’s control, such as permitting, the supply chain and financing as slowing construction.

“We have called on policymakers to advance policies that will help keep existing supply and bring new supply to the power grid,” PJM said. “We also ask that they analyze any state/local permitting challenges to the deployment of new generation resources and electricity infrastructure and enact policies to facilitate construction.”

O’Connell argued that PJM should have been ready for a wave of interconnection requests from renewable power projects because that same wave washed over other markets earlier and gummed up queues in the process.

“CAISO sort of got this wave of interconnection applications in the mid- to late 2000s, and so they developed the cluster study process, and they really thought through how to address the issue,” O’Connell said. “MISO got it earlier because there was a lot of wind development.”

Up until the mid-2010s, PJM was seeing some renewables, but not enough to slow down the queue that was initially developed with natural gas and other traditional generation in mind. Then, between 2017 and 2021, the wave came and queue entry rose by 293%, according to the analysis. The RTO then announced it would not be able to study projects again until 2026, and queue entry declined rapidly.

“They should have read the room, and they should have looked around and said, ‘Oh, this happened in CAISO; this happened in MISO; this happened in SPP. It’s going to happen to us; we should get ready,’” O’Connell said.

The issue with many projects making it through the queue and not being ready to start construction also can be tied to the delayed queue, he said: Projects faced yearslong delays that compounded the issues they were facing.

“They applied for interconnection in 2018, and now they’re trying to build that project that they had envisioned in 2018 and the world’s totally different,” O’Connell said. “Prices have gone way up. Maybe their permits expired.”

The analysis suggests PJM should adopt new software to help speed up interconnection studies. It could pair large loads with capacity meant to meet the demand and expedite it through the queue, or it could adopt something like SPP’s Consolidated Planning Process, in which generator interconnection and transmission planning are handled at once.

Another major improvement would be changing PJM’s governance process and giving states a bigger role, which is an idea supported by most of the governors in the RTO, O’Connell said. (See Governors Call for More State Authority in PJM.)

“The primary problem with PJM is its governance structure,” O’Connell said. “It’s kind of owned and run by incumbent transmission owners and generation owners. And in some sense, they don’t want competition. They don’t want these new resources online. And so, I think that’s why you’re seeing PJM sort of drag its feet, because the incumbent gas generators are doing just fine. They’re making lots of money as capacity prices go up. They’re getting windfall profits.”