Determining where to build new data centers is increasingly high stakes and complex with developers having to navigate electric grid infrastructure, fiber optic cables, environmental requirements and government policies.

With speed to power the paramount goal of developers, ICF International released a paper Dec. 17 titled “How to find the ‘sweet spots’ to build all those data centers.”

“It really is a synthesis of all the siting support work that we’ve been doing, really in the last decade or more, for our energy asset developer clients, and we have leveraged that experience in the last year and a half to support data centers,” ICF Vice President of Energy Markets and report co-author Himali Parmar said in an interview.

Before the recent growth in data centers, ICF’s main siting practice was focused on renewables and battery storage, and the two practices share some commonalities, Parmar said. Wind or solar facilities need a lot more land than data centers, but battery storage facilities have comparable footprints.

“Access and availability of the grid to accommodate you is extremely important, and it is common between energy assets and data centers,” Parmar said. “I’d say, amongst all the factors that we review for energy assets versus data centers, optical fiber was one thing that’s a new layer that we included as we develop the data center siting module. And the second one, [which] was not as important for renewable assets, was the gas infrastructure.”

Solar and batteries do not need access to natural gas infrastructure, but many data centers need pipelines nearby so they can be assured of reliable, around-the-clock power, she added.

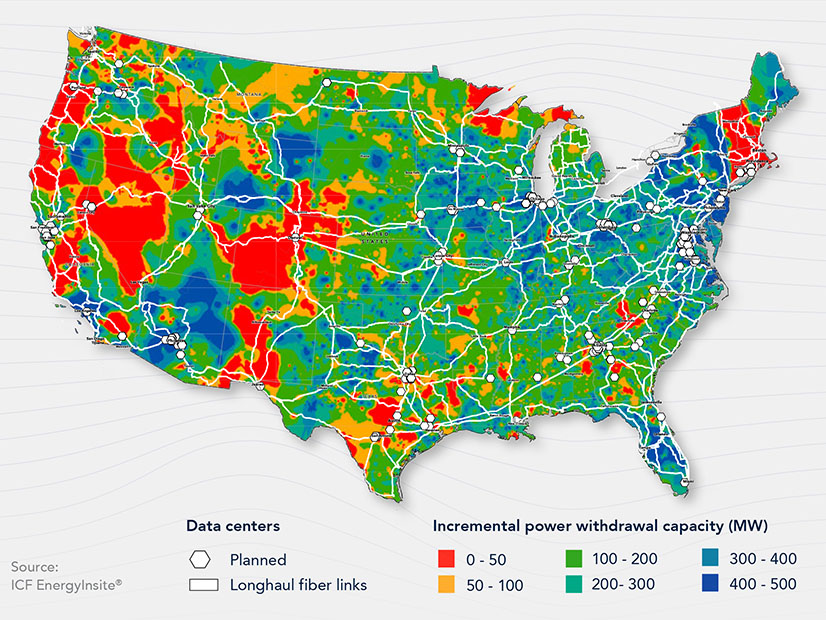

Energy typically carries the most weight in siting data centers because of their huge demand for power, which means parcels need access to electricity, the local grid needs some headroom for new demand, and the grid needs to be stable enough to ensure operational stability, the paper says.

“Historically, securing supply through interconnection to a utility-owned electric grid is the preferred choice for data center developers,” the paper says. “It provides the necessary level of reliability, has generally been sufficiently timely and does not require the data centers to have to undertake potentially complex and more costly energy management. However, sites where the electric grid has the capacity to serve data centers are disappearing rapidly as electricity demand skyrockets across the U.S.”

Data centers must ask utilities to interconnect to their grid, and it can take months of review that can add up to wasted time if a request is rejected.

“Utilities have an opportunity to offer proactive guidance to data center developers before they formally submit interconnection proposals, publish grid capacity maps for their service territories and publish preferred development zones that identify areas where favorable conditions for development converge,” the paper says. “These sources of information would help developers submit interconnection proposals with a higher chance of success. It would also allow utilities to save time on reviews and effectively plan for grid upgrades.”

The grid already is in a tight situation, with PJM load forecasts out to 2030 showing a reserve margin approaching 0% in some forecasts, Parmar said. That comes on top of well documented issues with the queue, along with supply chain difficulties.

That has some data center developers seeking out access to turbines wherever they can get them to bring facilities online as soon as possible, she added.

“A data center developer is not interested in the business of being an” independent power producer, Parmar said. “However, the challenges that they’re seeing in the grid not being able to give them the megawatts of supply that they need in a timely fashion is really the driver for why folks have started thinking about behind-the-meter power or direct offtakes.”

Behind-the-meter generation is viable only if the natural gas system also has some spare capacity, with the paper noting that pipelines are constrained, and some gas utilities expect new delivery bottlenecks in the next few years.

“Understanding pipeline networks and supply capacity is critical — both for developers considering gas turbines and midstream and downstream gas companies that may need to plan for new demand,” the paper says.