A regionally planned undersea transmission network interconnecting an expected surge in offshore wind projects would save New England developers and ratepayers more than $1 billion in onshore grid upgrades, The Brattle Group said in a study released Thursday.

Brattle prepared the study on behalf of transmission developer Anbaric Development Partners, which has proposed the Southern New England OceanGrid, an open-access network that would interconnect future offshore wind projects in the federal wind lease area off the coasts of Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

Brattle compared the costs of such a proposal to the expected costs under the current approach of each offshore project using one generator lead line (GLL) to interconnect to an onshore point of interconnection (POI). Four projects under development worth 3,112 MW — Vineyard Wind, Mayflower Wind, Revolution Wind and Park City Wind — already plan to use their own GLLs.

But New England will need possibly more than 40 GW of offshore wind by 2050 to meet states’ decarbonization goals — or as much as 1.5 GW every year, Brattle said. If every project followed the current approach, it could lead to major onshore transmission overloads, the group found.

“These overloads, and the massive amounts of marine cabling, could be reduced dramatically with a planned approach,” Johannes Pfeifenberger, a principal at Brattle, said in unveiling the study during a webinar hosted by Massachusetts-based State House News Service on Thursday.

Pfeifenberger explained that because projects would share HVDC lines under a planned approach rather than individual HVAC lines, in addition to reducing costs and congestion, a planned grid would also lessen the amount of marine trenching needed, mitigating damage to the undersea environment. Power line loss would also be reduced, as the length of cables would be shorter.

Brattle broke down its comparison into two phases: one based on states’ current procurements besides the four projects already expected to use GLLs (2.8 GW) and an expected extra 800 MW; the second based on using up the remaining lease area (about 8.2 GW).

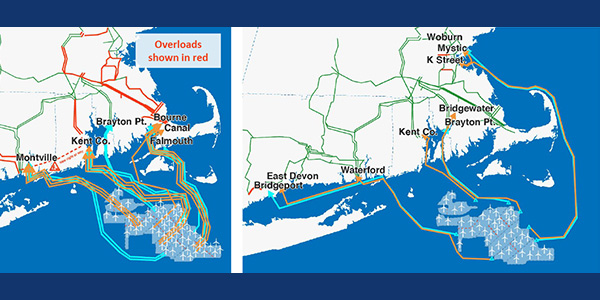

Under both the baseline scenario, which assumes projects continue to use their own GLLs, and the planned scenario, Phase 1 would see 3,600 MW in transmission capacity built. But under the current approach, nine HVAC lines stretching a combined 694 miles would be built, with “significant onshore transmission overloads” in Southeastern Massachusetts. Under the planned scenario, only three HVDC lines totaling 356 miles are built, with only “minimal” congestion near the POI at the Mystic Generation Station in Everett, Mass.

‘A Bowl of Spaghetti’

The differences become even more stark in Phase 2. In the baseline scenario, onshore transmission becomes even more congested and spreads across Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut. More individual GLLs are added, crisscrossing each other under the sea before they reach their POIs: “a bowl of spaghetti,” as Pfeifenberger described it, “of many lines; 18 [to] 20 lines emanating from the offshore wind lease area and interconnecting at various points onshore.”

In the planned scenario, additional HVDC lines are bundled with existing ones, untangling the “spaghetti” to create only four discernable routes to about the same number of POIs.

Overall, under Brattle’s planned scenario:

- total transmission costs are 10% lower, with a 65% reduction in onshore upgrade costs offsetting an expected 22% increase in offshore construction costs;

- line losses are about 40% lower;

- line mileage is about 49% lower; and

- ratepayers would save about $20 million annually.

“Importantly, you also create more competition under the planned approach,” Pfeifenberger said. “You would have people compete for building the offshore grid; then you would have wind developers for interconnecting their projects to onshore grid locations. … Offshore wind developers would not have to worry about the transmission component of their projects.”

The risk of stranded assets is also lessened, Brattle said.

“Without a well-planned offshore grid, some of the existing offshore lease sites may not be economic to develop,” the study says. “After developers interconnect the bulk of their lease sites, it may be cost-prohibitive to interconnect the residual areas (of perhaps 50 to 250 MW each) using AC generator lead lines sized to carry about 400 MW each.”

There’s also “a limited number of landing sites for offshore wind transmission in New England,” said Pfeifenberger’s associate at Brattle, Walter Graf. “If each offshore wind project requires a separate cable interconnection to the onshore transmission system, viable cable routes become really constrained.”

Anbaric and other transmission developers, eager to capitalize on the growing interest in offshore wind, have long been advocating for the benefits of offshore transmission planning. (See Anbaric Pushes Offshore Grid Plans.) But Brattle’s study appears to be the first attempt to quantify those benefits.

“Brattle’s research underscores the pivotal role of transmission policy in the development of New England’s offshore wind industry,” Anbaric said in a statement. “By relying on landing points closer to population centers and at robust onshore grid locations, a planned system reduces grid congestion and the need for expensive, disruptive onshore transmission projects that could hinder the growth of offshore wind.”

States have shown interest in such an approach. (See Mass. DOER Explores Transmission for OSW.) And webinar attendees, many of which were state regulatory staffers, were eager to get their hands on the Brattle study, if the side chat room in the webinar was anything to go by: Pfeifenberger repeatedly linked to his presentation as Graf spoke in response to requests from those apparently unaware they could see his previous answers.

Brattle compared a planned offshore grid to previous renewable-facilitating transmission projects, such as Texas’ Competitive Renewable Energy Zones and MISO’s multi-value projects. “New England could adopt a similar approach to planning transmission infrastructure to support offshore wind,” it said.