New York’s investor-owned utilities are working with government officials and project developers to fine-tune the processes and contract terms of state-mandated energy storage solicitations.

Approximately 60 energy storage developers participated Thursday in a technical conference hosted by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA), anonymously questioning a panel of three utility executives on matters such as expanding timelines for requests for proposals beyond the current six months; extending payment terms and contract duration up to 10 years; modifying in-service dates out to 2025; reducing the storage duration requirement from four hours to one; and providing developers the option to sell a project to the utility upon completion.

The New York Public Service Commission’s December 2018 storage order required Consolidated Edison to procure at least 300 MW of storage capacity and each of the other utilities (Central Hudson Gas and Electric, New York State Electric and Gas, Niagara Mohawk Power, Orange and Rockland Utilities, and Rochester Gas & Electric) to procure at least 10 MW each, with assets to be operational by Dec. 31, 2022, on contracts up to seven years.

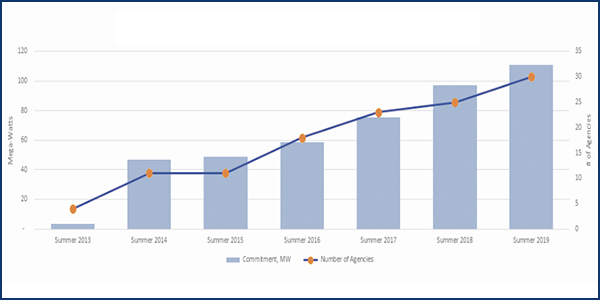

The RFPs started in 2019 and are to continue annually as needed to meet individual utility storage goals. New York state now has about 93 MW of advanced energy storage capacity deployed with 841 MW in the pipeline toward meeting its goal of 1,500 MW deployed by 2025 and 3,000 MW by 2030. The 1,400 MW of traditional pumped hydro storage in the state does not count for the goal totals.

Each utility has conducted its initial RFPs and is developing the next round of solicitations after having notified bidders of first-round results.

“We’re looking for feedback from the participants during this session as well as through a follow-up email [with comments due Oct. 8], and this will culminate in a filing with the commission, which will allow for more formal comments for commission action,” said Stephen Wemple, Con Ed vice president of regulatory affairs. The next round of RFPs is expected in the second quarter next year.

The PSC on Sept. 17 modified dynamic load management implementation plans for the six utilities, all related to storage, saying the initial plans “resulted in a bias towards short-term, low-capital investment solutions” because of their yearly performance structure (18-E-0130). (See “DLM Incentives Extension,” NYPSC Accepts CLCPA Environmental Review.)

Time and Negotiations

The feedback indicated that six months is very compressed for an RFP, from posting to final selection, and that developers need more time; whether a month or more is yet to be determined, said James Mader, manager of smart grid programs at NYSEG.

Mader addressed these questions: How does the current process flow? Does it start with bidders who have potential projects, or does the RFP require those opportunities to be concrete and ready to go?

“The current process was you’d look at the RFP and submit your bid once you received bidding approval, and then we would analyze and review what we received,” Mader said. “Moving forward, that’s something we’re looking to potentially tweak or adjust.”

The RFPs also required developers to have site control and to have applied for their interconnection agreement, which utilities factored into the viability of a project, Wemple said. “We want to go through a process; we want to select bidders that are well positioned to deliver and complete their projects in the time frame required.”

The first round of RFPs “was a learning experience for everybody, and the idea is to have a value-based bid cap — what is the utility actually going to get — and developers are going to give their best proposal in there,” said Schuyler Matteson, senior energy storage project manager at NYSERDA.

“For the utilities who are still under contract negotiations, and that includes Con Ed, we hope to make an announcement in the near future. … We don’t want to bias those negotiations, but there were a couple of utilities that did not have any finalists,” Wemple said. “I know that included my affiliate O&R.”

Central Hudson also reported no bidders that met the bid ceiling, while NYSEG said it was still in negotiations. National Grid did not take part in the panel but did participate in the conference planning and had a manager listening in, Matteson said.

Utilities received feedback that high pre- and post-commissioning security requirements increased bid prices; large upfront payments caused difficulties with financing for some developers; and annual payments did not cover operations and maintenance costs.

“From our perspective, we didn’t see anything that really jumped out at us to indicate that one offer or another was assuming things that were significantly different from anyone else,” said Jeffrey May, energy resource manager at Central Hudson. “To speak to the spread in pricing, there was nothing obvious to us that indicated a driver as to why some bids might have been significantly higher than others. … There were no offers that met the bid ceiling, so maybe if we had gotten into a deeper dive, we might have seen where some of those differences were, but there was nothing on the surface from our evaluation matrix.”

Tech Specs and COD

Utilities determined that a commercial operation date of Dec. 31, 2022, is not feasible for resources being procured in 2021 and proposed to move the date out three years to year-end 2025.

One question on that issue was whether the utilities could begin payments if a project comes online ahead of the date set by regulators. Wemple said Con Ed would.

Several developers provided feedback that uncertainty in the post-contract market led to attributing little or even negative value to merchant “tail” years, and that extending the contract duration from seven to 10 years would spread costs over a longer period while increasing potential contract revenue.

Developers said that removing the four-hour duration requirement would bring in a wider range of bids and address concerns related to buyer-side mitigation issues.

“I think the expectation is that a shorter-life battery, while perhaps not getting as much or any capacity value, could make up for it on its relative ‘less cells to pay for’ by providing regulation or other ancillary services,” Wemple said.

One commenter said that requiring a maximum number of cycles over the course of a year might be a good way to give bidders a sense of how the storage asset might be used.

Another commenter was concerned about “trying to align the NYISO class year process with knowing what the NYISO assignment of system upgrades are, because that impacts interconnection costs.”

“Hopefully we’ll get a little better clarity from the ISO on what their timing for the next class year process will be, and at least try to see if we can work that into this [RFP] process,” Wemple said.

One proposed revision to the RFP process would let the developer provide O&M services for a defined period (e.g., five years) and to mitigate uncertainty in post-contract market revenues by having the developer sell the project to the utility at the COD.

One developer asked whether the utilities are sure they can own storage in the first place.

“Certainly, with a commission order … the commission can allow us to do lots of different things, and actually in many cases, we already own storage as part of prior non-wires solicitations,” Wemple said.