Brattle’s analysis also shows Rhode Island demand outlook similar to New England, with moderate load growth through 2030 and significant growth after because of heating and transportation electrification. | The Brattle Group

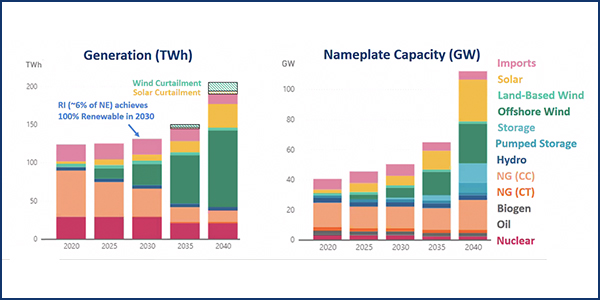

Rhode Island will need to add about 440 GWh of renewable energy annually to meet the state’s goal of 100% renewable energy by 2030, The Brattle Group said at the second in a series of three public workshops hosted by the state’s Office of Energy Resources (OER) on Sept. 29.

Equally daunting, the state will need to continue adding an average of 400 GWh a year to maintain the 100% target through 2050 as its load potentially doubles from the electrification of heating and transportation, Brattle said.

The consultants are helping state officials develop a plan by year-end for the clean energy target mandated in a January executive order by Gov. Gina Raimondo. (See RI Seeks to Lead with 100% Renewable Goal.)

Electrification Impact

At the first public meeting in July, the analysts said the state would need to add 360 GWh annually through 2030 to meet the target. The current estimate’s base case projects net load of 7,700 GWh in 2030, including electrification of 5% of light-duty vehicles (LDVs) and 5% of heating, based on an ISO-NE forecast, said Michael Hagerty, Brattle senior associate. The baseline also incorporates National Grid’s forecast for energy efficiency.

Michael Hagerty, Brattle | The Brattle Group

The baseline is bracketed by a low-demand scenario of 7,000 GWh and a high-demand scenario of 8,300 MWh, which assumes 15% LDV electrification and 10% heating electrification.

“In our low-demand scenario, we’re assuming that level of electrification does not occur,” Hagerty said.

The study says the state needs to add 4,400 GWh of renewable energy by 2030 to meet 100%. Last year, Rhode Island’s renewable electricity production of 930 GWh represented 13% of the state’s load. The state has 410 MW of renewables, including 230 MW of solar, including net metered resources, and 180 MW of contracted resources.

Current transmission queues list more than 12 GW of offshore wind, and 2.2 GW of onshore wind from Maine and 4 GW from New York. But the ISO-NE queue currently has no Rhode Island-based onshore wind because of wind quality and land availability, Brattle reported.

The costs of transmission and distribution system upgrades needed to accommodate the new renewables is “a source of significant uncertainty,” Hagerty said. “We’ve been reviewing these projections with renewable developers to make sure that they find them to be reasonable, and we’ve generally heard that they are.”

The limited availability of low-cost interconnection points for 1- to 10-MW scale distributed solar has resulted in increased interconnection costs, which might offset some of the cost declines seen in the industry, Hagerty said. An increase of $200 to $300/kW in system upgrades could increase distributed solar costs by $10 to $24/MWh, he added.

Wholesale Modeling

Brattle principal Dean Murphy outlined how the consultants are modeling the New England wholesale electricity market.

Dean Murphy, Brattle | The Brattle Group

“It’s important to recognize that the fundamental nature of this market is going to change substantially, even by 2030, and perhaps especially thereafter due to the significant addition of renewable energy generators across the system,” Murphy said. At 6% of regional load, “Rhode Island … is a very small component of New England overall, so it will be driven more by changes in other states that are also decarbonizing their electricity resources, albeit less quickly than Rhode Island.”

Because the output of renewables is highly correlated and difficult to store, once a lot of solar has been added to the system, incremental additions will have diminishing value. To capture how that dynamic will work out over time, Brattle uses an in-house model called GridSim.

Jurgen Weiss, Brattle | The Brattle Group

The study projects that gas-fired capacity will be kept around until 2040 but will be used much less than now as other renewable resources come online. In response to a question by an attendee, Brattle principal Jürgen Weiss acknowledged that gas generators will become increasingly dependent on capacity revenues to survive as their energy market revenue drops with lower utilization. He said the model accounts for the shift, ensuring all resources cover their fixed and variable costs.

“[It is] important to note that something similar is already the case since there are resources that don’t generate much electricity but stay in the market to provide reliability,” such as older dual-fuel units, he said. “If they have been built, you don’t necessarily need higher capacity prices since the capital cost is sunk and you just need to cover their going-forward costs,” Weiss said.

“Solar may be an excellent complement to wind, in part because it does generate more in the summer, when there is a summer peak for load in the daytime,” Murphy said. “A blend of these two kinds of resources is likely to be better than either one in isolation.”

Natural gas-fired capacity will be maintained into 2040 but will be used a lot less as other renewable resources come online. | The Brattle Group

Environmental Justice

OER Commissioner Nicholas Ucci told the workshop that his office is including social and environmental justice considerations in its work on clean energy.

“Folks should be comforted by the fact that we are accounting for many if not most of those categories in the 4600 framework, either analytically, qualitatively or by other means,” Ucci said, referring to the Public Utilities Commission’s Docket No. 4600, an investigation into the changing electric distribution system.

“One piece of good news is that, unlike in the past when dirty stuff was located in places that hurt particularly vulnerable populations, here we’re talking about locating renewable energy resources — and their negative impact on surrounding communities is considerably less than coal-fired power plants,” Weiss said.

How those vulnerable populations are protected from potential rate increases is a separate and important topic, Weiss said. “But we’re cleaning up Rhode Island’s electricity system, so the trajectory is to remove harm that might have been inflicted in the past. One can also ask whether the policies that are implemented to achieve the 100% renewable electricity target could be used to help those communities that are disadvantaged.”

For environmental justice, “the first step is to look inward,” Ucci said. “A lot of our state agencies are starting to connect with local grassroots organizations to better understand their perspectives [and] working to educate and train ourselves.”