San Francisco and Ojai, Calif., last week banned natural gas in new buildings, bringing the number of cities in the state that have adopted building codes to reduce their reliance on gas to 39, according to the Sierra Club.

Ken Costello | NARUC

While such bans have become increasingly popular in the push for electrification, they are an “exceptionally bad” way to attack climate change, regulatory economist Ken Costello told the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners’ Annual Meeting and Education Conference during a panel discussion Nov. 10.

“Less than 9% of carbon emissions in the U.S. are from direct use of natural gas in homes and buildings. The U.S. emits about 15% of world carbon emissions. Thus, under the condition where all buildings are converted to be electric and we have electricity produced only from clean sources, the reduction in worldwide carbon would be less than 1.5%, which would have no impact at all … on global climate,” said Costello, an independent consultant who formerly worked for NARUC’s National Regulatory Research Institute. “We know there’s more efficient ways to deal with climate change.”

‘Incongruent’

Richard Meyer, managing director of energy analysis for the American Gas Association, was also critical, saying natural gas is desired by consumers and that its infrastructure will be essential for decarbonizing. Bans represent “an all-or-nothing approach that seems incongruent with the size and the scale of the challenge” of climate change, he said.

Richard Meyer, American Gas Association | NARUC

Residential natural gas represents 4% of U.S. GHG emissions, with the commercial sector adding another 3%. “Residential natural gas emissions on average are about 250 million metric tons per year of CO2. That’s equivalent to two weeks of Chinese coal emissions,” Meyer said.

The third member of the panel, Amber Mahone, a partner in San Francisco-based consulting firm Energy and Environmental Economics (E3), acknowledged that U.S. natural gas use is a small contributor to worldwide GHG emissions.

“I would say there’s two reasons for action despite that fact,” she said. “One is the incredible power of the U.S. market to drive innovation. We’ve seen that with investments in solar and wind, bringing down the capital cost of that equipment dramatically and leading to widespread economic adoption of renewables. I think we could see similar innovation occurring in decarbonizing buildings, both with innovations in heat pumps as well as innovations with renewable natural gas. Bringing down the cost of biomethane and hydrogen would certainly be beneficial globally for reducing emissions.

“The other [reason] I would say is that deciding not to take action is a bit of a cop-out for one of the most advanced industrialized economies that historically has contributed to the predicament that we find ourselves in today.”

A Trend?

Although more than three dozen California cities have adopted gas bans, the idea has not taken root elsewhere.

Brookline, Mass., banned natural gas hookups in new buildings last year, but the state’s attorney general struck it down because state law pre-empted the city’s ordinance.

Meanwhile, Arizona, Tennessee, Oklahoma and Louisiana passed laws this year barring local governments from adopting electrification measures or natural gas bans similar to those in California, according to InsideClimate News. At least four other states introduced similar measures, it reported.

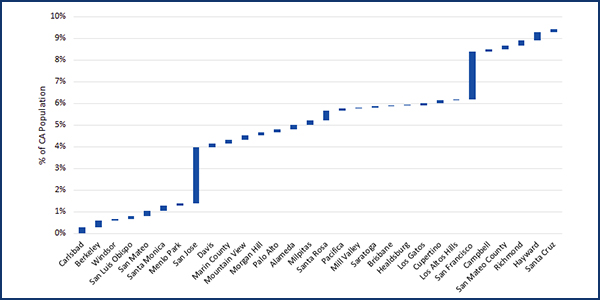

Percent of Californians living in jurisdictions with clean energy building codes | Sierra Club

Meyer said bans have been enacted without sufficient analysis on costs and benefits, including the strain on electric infrastructure and the impact on jobs, taxes, wages and low-income residents. “I’m not saying [carbon emissions from natural gas] can’t and shouldn’t be reduced,” he said. “I’m not saying they’re unimportant. Quite the opposite: AGA is committed to reducing GHG emissions through smart innovation, new modernized infrastructure and advanced gas technologies.”

But he said gas is the most affordable way to heat homes, with electric heat costing about 3.7 times as much. “The natural gas system today delivers a tremendous scale of energy to homes and businesses when they need it most. The gas system delivers about three times more energy on the coldest day of the year than the electric system does on the hottest.”

As evidence of consumer demand for gas, Meyer noted that although California has led the way on gas bans, it has also added almost 600,000 residential gas customers since 2010, more than any other state. He said natural gas and its infrastructure will be crucial to meeting climate goals, which some say will require a future “hydrogen economy.”

“One of the key ways to make hydrogen is via natural gas. And you can use carbon capture with a steam reformation process and have low-carbon sources of hydrogen,” he said. “Europe has … come to a recognition that you really do need to leverage the gas system to achieve your goals quickly, effectively and cost-efficiently. I think the U.S. will come to the same realization.”

No Easy Solutions

Mahone acknowledged that decarbonizing existing buildings is difficult and expensive, but she said their contribution to climate change is too important to ignore.

“All of the options on the table have challenges and costs if you look at the economics today. But we also know that reducing greenhouse gases is difficult in many sectors of the economy, including in the industrial sector and aviation and heavy-duty trucking,” she said. “So, if we shied away from one area where it looks hard, we might find ourselves not taking action anywhere. So, I do think it’s important to tackle greenhouse gases for buildings.”

Costs Vary by Region

Mahone also said the economics of replacing gas heating with electricity varies by region. In the Bay Area, she said, there has been a trend toward all-electric new construction, particularly in multifamily buildings, because of the cost savings and reduced permitting time from avoiding natural gas hookups.

Berkeley, one of the first cities to adopt a gas ban, has “a relatively mild climate. … We get an occasional winter frost and that’s about it,” she said. “We do see that electrification can reduce energy bills in some cases.”

Some colder regions are opting for dual-fuel heating systems, “where you can gain the benefit of high-efficiency heat pumps during most hours of the year and still have access to backup thermal heat in colder times,” she said.

She noted that Pacific Gas and Electric supported the Berkeley gas ban to avoid investments in new gas assets that may later prove to be underutilized. “That’s a pretty remarkable statement, I think, coming from a gas utility.”

Mahone noted that gas pipelines and distribution systems are typically financed and amortized over 30 to 50 years, meaning a gas line installed today would not be paid off until as late as 2070. “So, I don’t think that it’s exactly right to look at the economics of a gas ban just purely from the [position] of an individual customer, because the gas infrastructure that our regulatory environment supports is actually … socialized over many customers.

“The alternatives to electrification are quite expensive as well,” she added. “Renewable natural gas has supply limitations. We see it costing about $10/MMBtu today — three to five times the cost of fossil natural gas.”

She noted that while some research suggests the cost of green hydrogen — which uses renewable energy to produce hydrogen from water — may be reduced to between $11 and $20/MMBtu, it would still be well above the cost of fossil natural gas.

Geoengineering?

Costello said policymakers also could consider options for adapting to climate change rather than attempting to eliminate GHG emissions, such as geoengineering, which includes CO2 removal and solar radiation management, or sunlight reflection.

“If you look at the history of mankind, humans have adapted to very drastic conditions of climate and other things over time, and that’s sort of one way to deal with this. But I think the savior of all this is technology, innovation,” Costello said.

“Geoengineering … is somewhat controversial, but still, it’s an option that’s on the table. In fact, some of the best minds now are saying that we have to have a portfolio of different actions to deal with climate change. So far, we have disproportionately focused in on emission reductions.”