New York offshore wind developers have begun constructing the port facilities needed to build and operate their projects after the state completed the nation’s largest wind procurement last month.

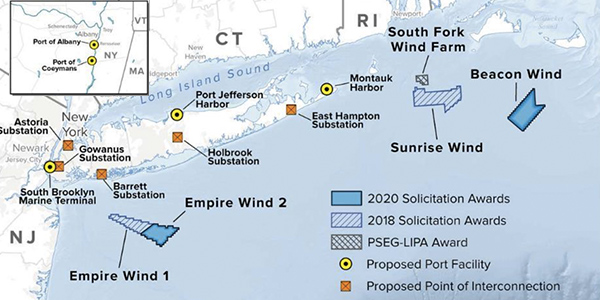

With the state’s 2.5-GW award to Equinor in January, New York has contracted nearly half of the 9 GW targeted for construction by 2035. Equinor and its partner, BP, will develop an additional 1,260 MW for their Empire Wind project in the New York Bight in addition to 1,230 MW for Beacon Wind, to be situated 60 miles east of Montauk.

The contract commits Equinor to develop the Port of Albany for tower manufacturing, including using the nearby Port of Coeymans for turbine foundation manufacturing, and to transform the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal (SBMT) into an assembly and operations and maintenance hub. (See NY Awards 2.5-GW Offshore Deal to Equinor.)

Partners Ørsted and Eversource Energy are building an operations and maintenance base at Montauk Harbor for the 132-MW South Fork Wind project. The companies are also developing a similar O&M base at Port Jefferson for their 816-MW Sunrise Wind project, as well as a facility in nearby East Setauket to serve both projects. (See BOEM Sees Moderate Impacts from South Fork OSW Project.)

For the Port of Albany, the developer has contracted with Marmen, a Quebec-based onshore wind turbine manufacturer, and Welcon, a Denmark-based manufacturer of OSW towers.

“That’s the premise of the Port of Albany, to combine one large manufacturer from Europe and another one from Quebec, who’s done more onshore than offshore, with the port itself in developing the site and the fabrication for towers and transition bases,” Anders Hangeland, Equinor head of East Coast development, told RTO Insider. “That’s bringing the best of prior experience in North America with the offshore experience from Europe in those two suppliers.”

“The offshore wind projects will furthermore leverage almost $3 of private funding for every $1 of public funding for a combined $644 million investment in resilient port facilities in the Capital Region and Brooklyn,” NYSERDA CEO Doreen Harris said on Wednesday as she announced the release of the agency’s 2021 Strategic Outlook.

A Fluid Process

Ports like SBMT and Albany had long been on the state’s radar as potential ports, Michael Lee, president of environmental planning and engineering firm AKRF, told RTO Insider. Lee’s firm spearheaded a project to make Port Cortlandt an OSW hub to use some of the industrial waterfront property near the imminently closing Indian Point nuclear power plant.

“The procurement process had the ports independent of the wind bids, then New York officials merged them last summer and made ports part of the total wind energy bids,” Lee said. “In a COVID world, it was very tough, so those who had an existing relationship were able to pull it together.”

NYSERDA originally said it would provide $200 million in grants toward ports development but changed it to $100 million in grants and $100 million in loans, with the private sector to come up with $444 million.

“All of this stuff is building blocks,” Lee said. “Step one is a port, and … you need to build the towers; you need to build the foundations, and COVID really restricted a lot of the abilities to get people to decide to do things.”

Equinor has not yet selected a turbine supplier, for which the contract doesn’t specify a certain date, but it is a normal part of the development process and the company will make the decision “when it makes sense,” Hangeland said.

“Bringing offshore wind from Europe, where it’s already a well-developed industry, to the U.S., which is an undeveloped area for offshore wind, is a question of how much can you build and manufacture on the East Coast itself, and how much would you need to transport from Europe,” he said.

Do European OSW contracts include similar development clauses?

“Obviously, as you see an industry developing, all the important pieces that make that industry viable develop, so in the beginning you have a bigger need for establishing such incentives,” Hangeland said. “As Europe has become more mature on this, all the different pieces needed to establish an OSW farm are in place, so incentives, whether on local content or on price, have gradually gone down as the industry has matured.”

Location, Location

Lee was impressed that the South Brooklyn Marine Terminal building, a staging facility, is behind a bridge — the Verrazzano-Narrows.

“To date, you’ll see all of the facilities on the Northeast coast or even what they’ve done in Europe, they like to build these things beyond any bridges,” Lee said. “I’ve heard there are videos to show how they can put this stuff on vessels and get it out underneath a bridge.”

Hangeland, however, said the height of barged material had already been considered in the planning, logistics and due diligence.

“If you look at how New York is central to all these markets, the SBMT is important because these are very big pieces of equipment and you can’t transport this stuff hundreds of miles,” Lee said.

Interstate cooperation around New York hasn’t happened like it has in the Mid-Atlantic, where some of the states are coming together, so most of the discussions have been state-by-state, but it was hard to discuss anything last year when “New York was slammed,” he said.

The governors of Maryland, North Carolina and Virginia in October agreed to collaborate to promote their states as a hub for the OSW industry. (See Md., NC, Va. to Team up on Offshore Wind.)

Another positive for the Brooklyn facility is that it’s an open port, so “it can be used for multiple contractors. Towers can be used for multiple contractors. They’re all independent of a particular technology, so I think it’s pretty strategic,” Lee said.