A Washington cap-and-trade bill designed to trim industrial carbon emissions faces a key vote in the state Senate this week after its chief sponsor spent a month fine-tuning the legislation.

Senate Bill 5126, sponsored by Sen. Reuven Carlyle (D), would require Gov. Jay Inslee’s office to appoint a task force by July 1 to lead brainstorming efforts on a creating a cap-and-invest program — essentially a cap-and-trade program with auction revenue going to programs for low-income residents and communities of color.

Preliminary recommendations would be due by Nov. 1, with final recommendations ready to be sent to the legislature by Dec.1. (See Cap-and-Trade Bill Emerges in Wash. Senate.)

The program would tackle facilities that emit 25,000 metric tons or more of carbon emissions annually. There are at least 100 such facilities in the state, including the oil, cement, steel, power industries and large food processing plants.

The bill contains many requirements that the task force must consider. These include the mechanics of measuring emissions and enforcing the proposed regulations, how to set up auctions in which companies would obtain their pollution limits, how the auction revenue should be distributed to disadvantaged communities, how to prevent industries from gaming the new system, and how environmental justice issues should be tackled. The bill anticipates the auctions would raise several hundred million dollars every budget biennium that the state government can allocate to low-income communities.

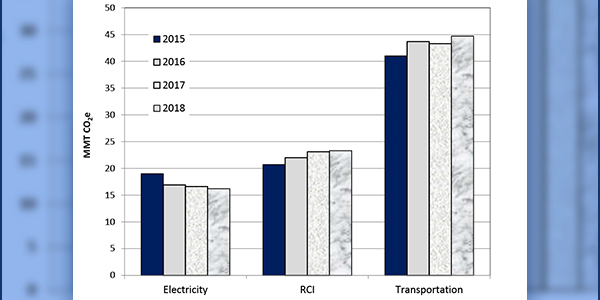

A 2021 Washington Department of Ecology report puts the state’s carbon dioxide emissions at 99.57 million metric tons in 2018. The report shows that from 2016 to 2018 the transportation sector was the largest contributor at nearly 45% of emissions, followed by industry (19%), electricity consumption (17%) and agriculture (7%). A 2008 law calls for overall emissions to be reduced to 50 million metric tons by 2030, 27 million metric tons by 2040 and 5 million metric tons by 2050.

Under Carlyle’s bill, the task force would create a system to set total industrial carbon emissions in the state annually — a cap that slowly decreases through the years. Four times a year, industries emitting 25,000 metric tons or more would submit bids to the state for segments of that year’s overall limit and be allowed to emit that amount in greenhouse gases. Companies will be allowed to trade, buy and sell those permits amounts.

“The bill will establish a declining cap on greenhouse emissions from the state’ largest emitters while giving companies flexibility to achieve reductions at the lowest costs,” said Denise Clifford, government affairs director for the Washington Department of Ecology, at a Jan. 19 hearing before the Senate Environment, Energy & Technology Committee on the bill.

At the hearing, Carlyle, chairman of the committee, said his bill combines market forces with regulatory oversight. “This package will lead us to a [Paris] accords level of emissions reduction. … A fierce urgency compels us to find a path forward.”

“It’s probably the biggest piece of legislation we’ve seen in some time,” said Sen. Doug Ericksen, ranking Republican on the committee and a leading opponent of the bill.

The committee is scheduled to vote Thursday on whether to recommend passage of SB 5126. If passed, it would go to the House Appropriations Committee followed by a full House vote before taking the same journey through the Senate.

Divided Opinion

The cap-and-trade concept first surfaced in Washington state in 2013, with Inslee first proposing it as a law in 2014. Until recently, Republicans hostile to major emissions measures controlled the Senate, discouraging the Democrat-controlled House from pushing any type of cap-and-trade measure. Democrats took over the Senate in 2018, building up big enough majorities in both chambers to provide cushions for this bill to potentially pass.

At the Jan. 19 hearing, reaction to the bill was mixed, leading Carlyle to spend a month revising it. Environmentalists were split on the concept, with some gung-ho about trimming emissions while others were hostile to the cap-and-trade concept.

Industry was also split with some not wanting expensive government regulations and others preferring well-defined stable pathways to combating global warming. Farm interests opposed the bill, arguing it would increase costs in a sector existing on thin profit margins. Unions were also split on the bill.

Ericksen, one of the state’s leading climate change skeptics and a strong ally of Washington’s five oil refineries, argued there is a lack of data that shows capping carbon emissions will aid the fight against global warming. He also voiced dismay that large companies could end up paying for programs for low-income people.

Among environmentalists, several organizations supported the bill, focusing on its efforts to trim carbon emissions.

“We concluded a cap is absolutely essential to bring emissions down,” said David Giuliani of the Low Carbon Prosperity Institute. David Mendoza of the Nature Conservancy added: “We need strong enforcement with strong accountability provisions.”

However, environmental justice groups — focusing on how pollution often disproportionately affects low-income communities and communities of color — argued that carbon-emitting industries can buy and sell their permitted carbon allocations in ways that avoid complying with the spirit of cutting GHGs. Heavier polluters are frequently located in disadvantaged areas, they said.

“It flows to communities where it is cheapest to pollute,” said Debolina Banerjee of Puget Sound Sage. Jill Mangaliman of Got Green said: “We have no interest in markets and offsets and trading credits; we just want to live healthy lives.”

Environmentalist opponents cited a 2019 ProPublica story that concluded polluters have manipulated California’s cap-and-trade program to the point where that state’s emissions did not decrease. Those opponents preferred a straight tax on carbon emissions in a bill (SB 5373) introduced a few weeks ago by Sen. Liz Lovelett (D). However, her bill has not had a hearing yet in the Senate Environment, Energy & Technology Committee.

A committee staff memorandum said the task force to be created by Carlyle’s bill would need to address safeguards against businesses gaming a cap-and-invest system.

Carlyle’s bill has language that would provide some breaks to emitting industries that are economically vulnerable to foreign competitors.

Ericksen was unhappy that oil refineries were not included in the state ecology department’s current list of such vulnerable industries, arguing the refineries export oil that competes with other nations’ petroleum exports. Carlyle replied that most of the five refineries’ oil stays within the Pacific Northwest.

Stu Clark, a special advisor to the state’s ecology department director, said the list of industries vulnerable to foreign competition is a political one because there is no state regulatory criteria defining what makes a plant vulnerable. He said Carlyle’s bill orders the ecology department to come up with such criteria.

Carlyle told Ericksen: “It’s a legitimate policy issue that you’ve put on the table. … It does warrant additional consideration.”

On Thursday, Carlyle added the state’s oil refineries to the list of industries needing a break due to foreign competition.