California’s energy policy leaders came together Wednesday to weigh the potential impact of the state’s sharply rising electricity rates on its carbon reduction and electrification goals.

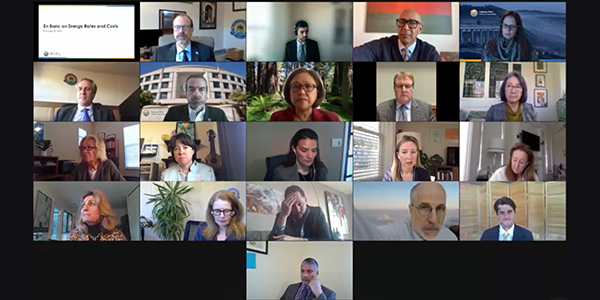

The heads of CAISO, the state Public Utilities and Energy commissions, and the legislative committees that oversee energy heard from CPUC staff and academic experts in a virtual hearing on how escalating rates could exacerbate the state’s division between rich and poor and undermine its ambitious programs to fight climate change.

“We begin this work because we understand that meeting our state’s decarbonization and electrification goals will depend on maintaining electricity rates that are affordable for customers,” CPUC President Marybel Batjer said.

Those goals include serving retail customers with 100% carbon-free energy by 2045 and requiring that all new cars sold in the state be zero-emissions vehicles by 2035. (See Calif. Governor Proposes $1.5 Billion for ZEVs.)

In the next decade, however, rates charged by the state’s three big investor-owned utilities will outstrip inflation by a wide margin, CPUC staff said. Ratepayers will have to cover the costs of billions of dollars in wildfire mitigation strategies and transmission and distribution upgrades.

The result: Southern California Edison’s rates will rise by 3.5% annually through 2030; Pacific Gas and Electric’s rates are projected to climb by 3.7% a year; and San Diego Gas and Electric’s rates will increase 4.7% every year for the next decade. Annual inflation, meanwhile, is anticipated to be about 1.9%. And PG&E and SDG&E’s annual rate increases have been twice the rate of inflation since 2013, commissioners said.

Electricity costs outpacing inflation by such a wide margin is a “very troubling finding,” Batjer said. Though not as dramatic as some had feared, the increases are more likely to hurt lower-income households that are sensitive to even small increases in monthly bills, she added.

The state must figure out how to maintain affordability and reliability while continuing to fight climate change, she said.

Batjer and the other CPUC commissioners were joined on the virtual dais by CAISO CEO Elliot Mainzer and members of CAISO’s Board of Governors, the state’s energy commissioners, and the chairs of the Senate and Assembly energy committees.

CPUC Commissioner Genevieve Shiroma called the unusual gathering a “who’s who of California energy.”

Shiroma led the effort that produced the draft white paper that formed the basis for the hearing and future efforts. She said it wasn’t fair to keep saddling ratepayers, regardless of income, with fixed costs for infrastructure upgrades.

“We as a commission cannot continue to approve larger and larger revenue requirements,” she said. “We need to do a better job of considering the cumulative impact of the rate increases we approve … and we need to be diligent in ensuring that … we approve [increases] only for programs where we have strong evidence that the benefits will outweigh the costs.”

A primary concern is that rising electricity rates will prevent the adoption of electric vehicles and the replacement of gas furnaces and water heaters with electric units.

California is among the states with the highest retail electricity prices , averaging 20.45 cents/kWh in December versus the national average of 12.8 cents/kWh, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

That could thwart the electrification of transportation, a major policy goal in California, with about 800,000 electric vehicles currently on the road and millions more anticipated. The movement to electrify buildings has been rapidly gaining momentum, with dozens of cities and counties adopting electrification ordinances that exceed state building codes in recent years.

“Higher bills make meeting our policy goals much harder,” CPUC Energy Division Director Ed Randolph said.

The white paper describes the problem but does not provide immediate solutions, Randolph said. Among the issues lacking ready alternatives is the state’s need to prevent catastrophic wildfires sparked by utility equipment, such as those in 2017-2020, and rolling blackouts like those in August.

“Once we looked at the drivers of the increases and the ways we could reduce utility costs, it was hard to pinpoint places where we should cut back on spending,” he said. “The biggest drivers of bill increases are wildfire mitigation spending and transmission buildout. While we can look at ways to be more efficient in these investments, I don’t believe we can recommend not making [them]. They are critical to reducing wildfires, maintaining reliability and avoiding outages such as the ones that happened last summer in California and just happened in Texas.

“We also know that investments in clean energy infrastructure are absolutely necessary to meet our state policies, and analysis shows that these investments have minimal impact on bills or could even save Californians money over time” by reducing rates because of increased demand, he said.

The CPUC and its sister agencies, utilities and stakeholders must find ways to minimize costs and keep electricity affordable, Randolph said.

“Hopefully this en banc [hearing] is a start of that joint effort,” he said.

‘A Tale of Two States’

Paul Phillips, CPUC manager of retail rates, said the rate dilemma highlighted the often extreme income equality in California.

“It really has become a tale of two states,” Phillips said, while presenting the white paper’s findings. “We have wealthier coastal homeowners who tend to invest in distributed energy resources,” mainly rooftop solar, and have a better sense of how to lower their own electric costs. Inland communities of lower-income workers don’t have those resources, he said.

In an afternoon session, Severin Borenstein, a CAISO board member and University of California, Berkeley professor, echoed the theme. He presented the results of a study he and two colleagues from the Energy Institute at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business authored, titled, “Designing Electricity Rates for An Equitable Energy Transition.” Nonprofit think tank Next 10 commissioned the study.

The report said California’s strategy of recovering fixed utility and social program costs from lower-income ratepayers is “a headwind in the state’s efforts to combat climate change through electrifying transportation and buildings, which many see as critical steps to a low-carbon future.”

“The state’s three large investor-owned electric utilities recover substantial fixed costs through increased per-kilowatt hour (‘volumetric’) prices,” it said. “With nearly all fixed and sunk costs recovered through such volumetric prices, the price customers pay when they turn their lights on for an extra hour is now two to three times what it actually costs to provide that extra electricity — even when including the societal cost of pollution.

“This massive gap between retail price and marginal cost creates incentives that inefficiently discourage electricity consumption, even though greater electrification will reduce pollution and greenhouse gas emissions,” the report said.

Between 66 and 77% of the costs that California IOUs recover from ratepayers are “associated with fixed costs of operation that do not change when a customer increases consumption,” it said. “This includes much of the costs of generation, transmission and distribution of electricity, as well as subsidies for low-income household and public purpose programs, such as energy efficiency assistance.”

The shift to behind-the-meter solar generation has disproportionately shifted cost recovery onto customers who do not have rooftop solar, the report said. More affluent homeowners now consume “modestly” more energy than low-income households, it said.

The study recommended changing the way utility infrastructure and social programs are financed. One approach, it said, would be to raise revenue from sales or income taxes, “ensuring that higher-income households pay a higher share of the costs.”

That might not sit well with voters, it acknowledged.

“A more politically feasible option could be rate reform — moving utilities to an income-based fixed charge that would allow recovery of long-term capital costs, while ensuring all those who use the system contribute to it,” the report said.

“In this model, wealthier households would pay a higher monthly fee in line with their income.”

In his presentation, Borenstein said the state’s Franchise Tax Board could either provide refunds to low-income ratepayers or disclose customers’ income brackets to the utilities that collect the fees.

“We’ve thought about enforcement issues, and we think there are ways to do it,” Borenstein said. “It would be a lift, but the alternative is not only, I think, going to undermine decarbonization but, also, we’re basically balancing the costs of all of the carbon-reduction programs on the backs of the people who are least able to pay for it.”