When congressional Democrats first introduced the Climate Leadership and Environmental Action for our Nation’s (CLEAN) Future Act in January 2020, it was already a mammoth 622 pages long. But the updated version of the bill before the House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Environment and Climate Change now weighs in at 981 pages.

The bill sets out a comprehensive roadmap for the U.S. to cut carbon emissions 50% by 2030 and reach net-zero by 2050. A hearing on Thursday ― the bill’s initial outing since it was formally introduced March 2 ― provided a view of the wide gap in policy objectives between Democrats and Republicans on the subcommittee, which will be a challenge to the bipartisan collaboration both sides said they seek. The bill will get a second hearing before the Subcommittee on Energy on March 24.

Democrats focused on the bill as a job and innovation generator, with special provisions targeting environmental justice communities and workers and communities that have or could lose jobs as a result of the nation’s transition away from fossil fuels.

Rep. Frank Pallone (D-N.J.), chair of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, called out three of the new programs and projects added to the updated bill:

- A green bank-style Clean Energy and Sustainability Accelerator with $100 billion in funding would help states, cities, communities and businesses finance a range of clean technologies, infrastructure and resiliency projects.

- An expanded Buy Clean program for federal procurement would include a new Climate Star program, similar to EPA’s EnergyStar program. Climate Star would rate and promote industrial products, such as cement and steel, with low-carbon footprints, particularly for federal procurement.

- An Office of Energy and Economic Transition at the White House would coordinate federal action to support workers and communities affected by the transition. Funding would be available to set up one-stop community organizations to advise and help workers connect with training, counseling and employment opportunities, as well as other “wraparound” services.

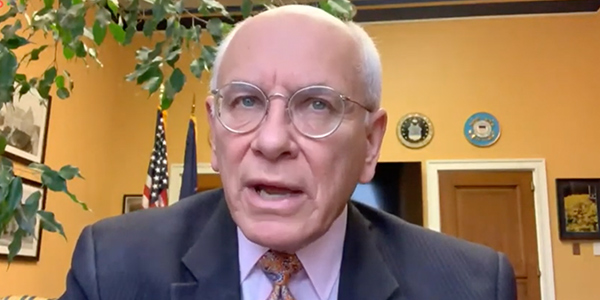

Subcommittee Chair Paul Tonko (D-N.Y.) stressed the bill’s recognition of regional differences in decarbonization strategies and impacts. “It’s not for me or anyone else in Washington to try to dictate these transitions,” Tonko said. “It must be a community-driven process, since every affected community will have different needs, different wants and different assets. The CLEAN Future Act provides federal resources and technical assistance to empower local community leaders to manage their own economic transitions.”

Rep. David McKinley (R-W.Va.), the subcommittee’s ranking member, fired back, saying that decarbonizing the U.S. economy would “destroy our livelihoods, disrupt families, decimate communities, increase utility bills [and] threaten the stability of our grid,” without curbing the impacts of climate change.

Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.), ranking member of the committee, raised concerns that a clean energy future based on wind, solar and battery energy storage would leave the U.S. too dependent on Asian supply chains, particularly those from China. She called for a market-based approach “to reduce regulations in order to deploy new, cleaner technologies more quickly and at a lower price. This path rejects one-size-fits-all central planning.”

Tackling Industrial Emissions

Other provisions in the bill, such as requiring utilities to join RTOs or ISOs, were not discussed on Thursday. (See Draft Climate Bill Would Make RTO Membership Mandatory.) Rather, experts providing input and suggestions at the hearing largely drilled into provisions targeting industrial emissions.

Rebecca Dell, director of industry programs at the ClimateWorks Foundation, underlined the importance and potential impacts of decarbonizing federal procurement through the Buy Clean and Climate Star programs.

“Buy Clean policies require or incentivize the government to buy building materials made with cleaner processes. The environmental stakes are not small,” Dell said. Ambitious plans for rebuilding and expanding U.S. infrastructure could generate “an additional 200 million tons of CO2 emissions from making the associated building materials.”

“Cement is responsible for the largest share of emissions in public construction, but it only accounts for about 1% of the cost of projects,” Dell said. “Because it’s such a small portion of the total cost, even if clean cement is more expensive than conventional cement in the near term, it won’t significantly change the overall cost of infrastructure.”

Industrial emissions currently make up 29% of the country’s total carbon emissions but are difficult to decarbonize because of their “tremendous diversity and reliance on a large quantity of energy and heat,” said Bob Perciasepe, president of the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions and a former EPA deputy administrator. A number of renewable thermal technologies ― such as geothermal, green hydrogen and concentrated solar power ― could provide lower-carbon alternatives, Perciasepe said, but federal leadership is needed because efforts at the state level have been fragmented.

He sees the Clean Energy and Sustainability Accelerator as “a financial facility that will help accelerate the deployment of those innovations as they occur, getting to that next step of implementation and deployment.”

Kevin Sunday, director of governmental affairs for the Pennsylvania Chamber of Business and Industry, provided a counterpoint, stressing the importance of natural gas as an economic engine for his state and the country — and its ongoing role in lowering commercial and industrial carbon emissions.

“The United States has lapped the European Union in growth over the past decade and a half, while reducing emissions more, and our energy prices are much lower,” Sunday said. “We’re seeing natural gas and renewable resources being paired together to develop resilient microgrid projects and critical infrastructure like airports and the Navy Yard in Philadelphia. Combined heat and power projects are helping universities, hospitals, systems manufacturers, and pulp and paper and food product segments manage costs and improve sustainability.”

He called for permitting reforms to help drive innovation and infrastructure growth. “It takes entirely too long to build any new infrastructure in this country if that project is touched by the National Environmental Policy Act,” Sunday said. “It is imperative we streamline the federal decision-making process.”

Jason Walsh, executive director of the BlueGreen Alliance, was focused on provisions in the bill that would help grow U.S. manufacturing, competitiveness and union jobs.

“I want to note, in particular, the act’s establishment of an interagency transparency and disclosure program to enhance the quality and availability of data used to calculate emissions of [Buy Clean]-eligible materials and strengthen our understanding of the competitiveness of U.S. manufacturers across industries,” Walsh said.

“America’s energy transition is well underway, but a transition that is fair for workers and communities isn’t something that will happen organically,” he said. “We need a broad, holistic, governmentwide response. We should be clear that the best approach to the energy transition among workers and communities and sectors not already impacted is one that prevents economic disruption and employment loss before it happens.”