By Patrick McGarry

As long as there are history books, Neil Armstrong will be in them.

Armstrong was a naval aviator, test pilot, astronaut and a university professor.

He was also an engineer.

On Feb. 22, 2000, Neil Armstrong delivered a riveting speech to the National Press Club, putting forward the idea the 20th century could, in some sense, be thought of as “the engineered century.” He confessed to being a “nerdy engineer” and spoke about how engineering achievements changed the quality of life in the 20th century.

He outlined the National Academy of Engineering’s top 20 choices for the greatest engineering achievements of the 20th century.

No. 1 on the list?

The electricity grid.

This “story of public and private investment”, wrote the NAE, made possible “the modern world as we know it.”

I recalled Armstrong’s speech during the past few months as I listened and read various commentaries from our politicians, regulatory folks and general media regarding the Great Winter Storm of 2021.

After digesting three weeks of various theories, accusations and solutions, as well as rereading Armstrong’s speech, I arrived at two simple conclusions.

All is not lost.

We need more engineers.

Perspective

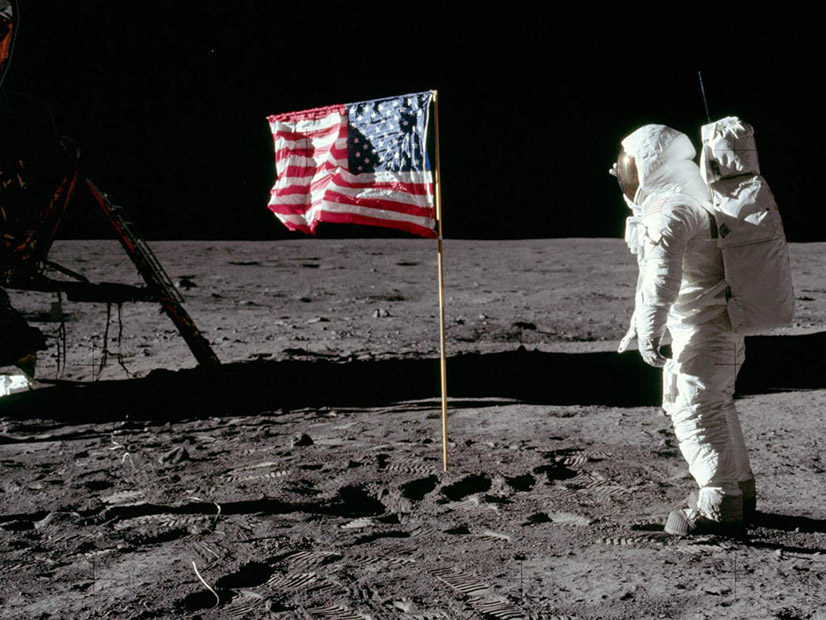

I was five years old when Apollo 11 landed on the moon in 1969. We watched the lunar landing on a black-and-white Magnavox television in our living room. Some memories last a lifetime. (Including watching The Miracle Mets win a World Series a few months later on the same television!)

The Apollo mission transformed our understanding of our planet.

But it only ranked #12 on the NAE top 20 based on its effect on the quality of life.

Just to provide a little perspective on progress, the iPhones glued to our hands today have more than 100,000 times more processing power than the computer that landed astronauts on the moon nearly 52 years ago.

We live in a world completely consumed with the latest technology gadget and a belief that algorithms will solve every problem. Artificial intelligence may even cure cancer soon.

We also, unfortunately, live in a world where people want to be understood before understanding. A world of binary thinking and polarized debates.

In the world of maintaining and enhancing the power grid, that type of thinking and discourse is not only fruitless, it is dangerous.

We used to encourage, appreciate and value our engineers. But I am not so sure anymore — especially in regard to our senior engineers.

I hear people use terms like “boomers” and “dumb old utility guy” who simply don’t get it and are stuck in the past.

And that is regrettable.

The Grid Today

The economy, national security and even the health and safety of our people are all dependent on effective electricity delivery. With more than 9,200 electric generating units and more than 1 million megawatts of generating power connected to more than 600,000 miles of transmission lines, the U.S. electric grid is an engineering marvel.

More than just generation and transmission infrastructure make up the electric grid. It’s a complex network of asset owners, suppliers, service providers and federal, state and local government officials all working together to maintain one of the world’s most stable power grids.

At least until recently.

According to S&C Electric Company and business consultant Frost & Sullivan’s “2021 State of Commercial and Industrial Power Reliability Report” the number of businesses impacted by power outages lasting less than 5 minutes increased from 20% to 40% from 2019 to 2020. And 44 percent of businesses said they lost power on a monthly or more regular basis, which is more than double the number of outages recorded in 2019.”

According to Paul Cicio, president and CEO of the Industrial Energy Consumers of America, power quality is “consistently getting worse.”

Public Utility Commission Compositions

The Public Utility Commission is expected to represent consumers’ interests, while allowing the utility to earn enough profit. However, since they operate in a highly political setting and regulate one of the most complex processes ever devised by humanity, regulators can face conflicting incentives.

Public utility commissions face a “revolving door” problem since each new election often brings in new regulators.

But what about the composition of these regulators?

The majority of public utilities commissioners are not engineers. Most political appointees have backgrounds in law or public service.

While you certainly need lawyers to ensure decisions are made that comply with existing public utility law, what about the need to fully understand the complexity of how the power grid works?

In truth, the power grid is a delicate mystery known to very few.

While some state regulators have access to engineering expertise, many do not.

Can we afford not to have some level of engineering expertise on public utility commissions, considering all the challenges to the grid today?

I argue that we should consider some tenured representation of certified electrical engineering experts on these commissions.

Why are engineers some of the most ethical people you will meet professionally?

The things they help design, build and maintain could result in a loss of life, if they put profits, personal advancement or anything else in front of people.

We clearly need more engineers on public utility commissions.

Roger Boisjoly & The Management Hat

Roger Boisjoly.

Even if you don’t remember his name, you’re probably familiar with his story: He was one of the Morton Thiokol engineers who attempted, but failed, to avoid the Challenger space shuttle launch in 1986.

When NASA overruled the Thiokol engineers, they said something that no one who deals with data on the front lines of a project can ever forget:

“Take off your engineer hat and put your management hat on,” they told Boisjoly and the others.

As a result of that recommendation, seven people were killed, and the U.S. space program experienced a significant setback.

When it comes to tinkering with the greatest engineering achievement of the 20th century, the power grid, we ignore the role of engineers at our peril.

In 2021, we still struggle with the simple concept that some things don’t work when it gets really cold outside, just as we did in 1986.

Sometimes we do not like the answers we hear, even when we know they are correct. So we shoot the messenger.

Conclusion

In Armstrong’s 2000 speech, he wrote “Engineering is a profession which leaves its imprint on our society in countless ways. We all intuitively understand the term ‘quality of life,’ but we have difficulty in attempting to define it.”

In regard to the power grid, I believe that we all own a basic understanding of the value of grid reliability to our economy, our safety and our national security. But very few people own the technical expertise to understand all the potential impacts of public policy to our grid.

Engineers comprise most of the few.

We should avoid the politics of fear in grid discussions, because it only delays the inevitable. At the end of the day, we will need to adopt engineering solutions to solve complex grid problems and achieve public policy goals.

Let’s include engineers of all experiences and ages to solve these problems.

I am pretty sure old Neil Armstrong would have agreed.

Patrick McGarry is senior director at Power Costs, Inc.