In a sign of the growing threat of utility-sparked wildfires in the Pacific Northwest, the Bonneville Power Administration will this summer join the ranks of Western transmission providers adopting a public safety power shutoff (PSPS) plan.

The plan will allow BPA to pre-emptively de-energize specific power lines under conditions of high fire danger in order to prevent its equipment from sparking a conflagration like those that engulfed large heavily forested areas of Western Oregon last September. The complex of wildfires, unprecedented for a normally lush region, prompted widespread evacuations, destroyed thousands of homes and blanketed the region in heavy smoke for more than a week. At least 11 deaths have been attributed to the event.

A lawsuit blames Pacific Power, the state’s second largest utility, for one of the fires, although the cause is still under investigation. (See High Fire Danger Prompts First Oregon PSPS Event.)

“I think it’s important to recognize that the risk of fire has always been a risk with operating any transmission system. One of the things that has changed is climate change,” Michelle Cathcart, BPA vice president of transmission system operations, said Tuesday during a virtual workshop to elicit feedback on the plan.

“We’re seeing increasing winds, heat and drought throughout our region. Wildfire will likely continue to be an increased risk to our system,” Cathcart said.

With more than 15,000 miles of power lines under its control, BPA is the largest transmission operator in the Northwest. Just 2% of its network will be subject to the new PSPS protocol, agency officials said Tuesday, although they would not identify those lines because of “safety reasons.”

“As we look at this, while we haven’t specifically excluded any facilities from the possibility of a PSPS, we are focusing on our lower-voltage system, largely 115-kV and below,” Cathcart said. “We recognize the role that Bonneville has in the region in supporting the backbone of our transmission system, and so we are focusing on the parts of the system that have greater risk for wildfire.”

‘Last Resort’

In what appeared to be an attempt to dispel concerns about the potential scope of shutoffs, Cathcart characterized the PSPS program as “risk-based, facility-specific [and] condition-specific.”

“But it is something that we feel is prudent to have a process for and to be clear and coordinated with you as our customers on how we are doing this,” she said.

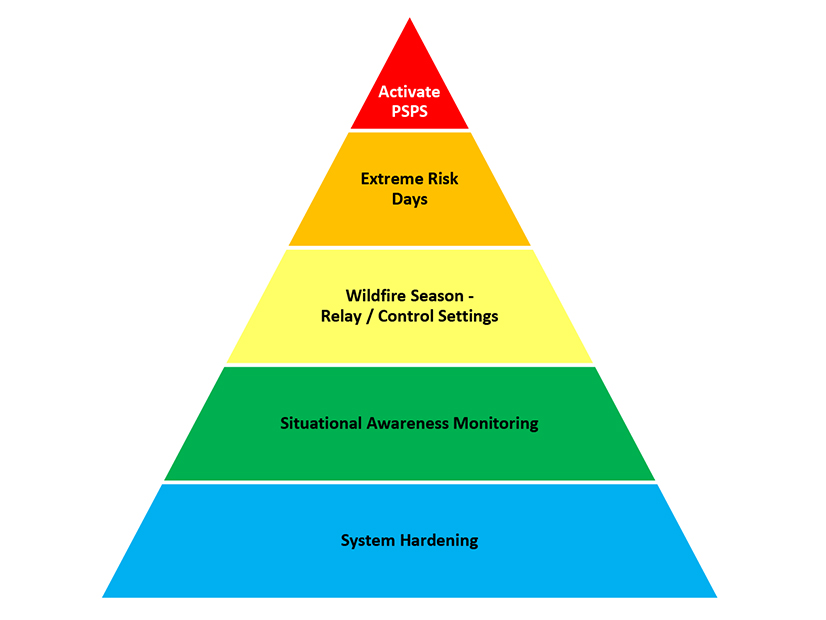

Meg Albright, BPA operations support manager, said the PSPS proposal fits into the agency’s broader wildfire mitigation plan (WMP), comprising a “tiered approach” to preventing wildfire ignition.

“Only as a last resort would we get to activating PSPS,” she said, showing a slide in which PSPS represented the pinnacle of a WMP pyramid.

Sitting at the base of that pyramid is BPA’s “system hardening” efforts, explained Dan Nuñez, BPA asset management risk and strategy expert.

Nuñez said BPA identified the “emergent threat and volatility” of wildfires in its 2016 strategic asset management plan, compelling the agency to factor the speed of climate change into its capital allocation strategy.

“And though we look at many risk dimensions and value streams to the region, wildfire absolutely is at the top of the priority list in informing where we’re allocating and prioritizing resources for line rebuilds,” including incorporating hardware redundancies into infrastructure located in areas of high ignition potential, he said.

The next tier of BPA’s wildfire mitigation plan consists of “situational awareness monitoring.”

“We have been noticing our fire seasons getting longer, and the longer those fire seasons get, the greater the chance that you’re going to have a ‘red flag’ situation, [with] very dangerously low humidity, very dry fuels, maybe even lightning — combined with a high-wind event,” said Erik Pytlak, BPA’s supervisory meteorologist.

Pytlak said those conditions alone would not cause BPA to shut down a line but would “trigger the analysis to start looking more intently at the possibility of needing to do this.”

Nuñez credited BPA’s investment in improved line design standards with providing the agency “a much higher trigger threshold” for initiating the PSPS process compared with its “peers south of us” in California. Design redundancies also mean that PSPS events will not necessarily translate into a loss of load or generation for BPA customers, Cathcart said.

Further up the WMP pyramid are the preparations on days of extreme risk, which will entail standing up the PSPS decision team and coordinating with the U.S. Forest Service. Before activating PSPS, the decision team will assess local weather conditions and its confidence in the forecast; load and generation impacts to customers; impacts on grid reliability and stability; information about critical loads, where possible; and the potential wildfire risk from BPA equipment in an affected area.

Each asset will be evaluated base on its distinct profile, Albright said.

Coordination, Communication

Once the decision is made to trigger a PSPS, BPA operations and dispatch personnel will contact counterparts at adjacent utilities through “normal utility-to-utility operations channels.” BPA hopes to provide customers with at least 48 hours’ notice before de-energizing a line, Albright said. But Pytlak cautioned that changing weather conditions could warrant shorter notice: “We can’t anticipate every scenario that’s going to determine whether we need to de-energize a line or not.”

BPA customer account executives will reach out to customers and stakeholders by telephone and email, while using the agency’s website and social media platforms to inform media and the general public about developments.

Workshop participant Joe Lukas, general manager of Western Montana Electric Generating and Transmission, asked what input a local utility would have on a PSPS decision that would force it to take an outage.

“For the local utility or utilities in the area, they will have the same weather conditions … and will very likely be considering PSPSes of their own, so we will want to talk operations to operations to understand that collective PSPS picture so that we’re understanding how our decision and their decisions are playing together,” Albright said.

“We do intend to coordinate with the customer,” Cathcart added. “Ultimately, it will be Bonneville’s decision on whether or not we will de-energize a specific facility, but understanding the impact of that will be important.”

Washington state Rep. Ed Orcutt (R) asked about the impact on retail electricity customers.

“I know sometimes when you shut a line down, you can reroute power in other directions so the people don’t lose power,” Orcutt said. “How are we going to know, when you’re announcing that you’re shutting down a line, what impact that’s going to have on who and for how long?”

Cathcart reiterated that it’s an open question whether a PSPS will result in a loss of load. “And that’s why we have to coordinate so closely with the local utilities. I think we’re going to need to rely to some degree on that coordination to make sure that the word gets out to end-use customers.”

BPA has asked stakeholders to comment on the PSPS proposal by May 11 and will reply to those comments by May 22. It expects to issue a final plan June 1.