By Michael Kuser

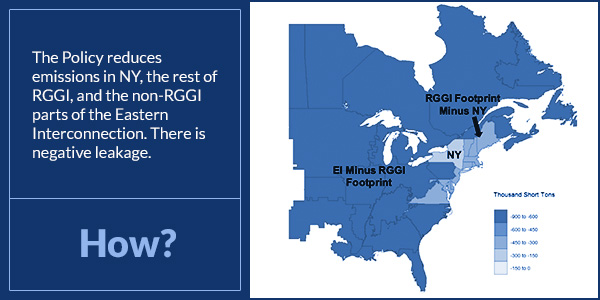

RENSSELAER, N.Y. — An independent study suggests New York’s effort to price carbon into its electricity market could result in reduced CO2 emissions from generators in neighboring areas, rather than an uptick due to “carbon leakage,” the state’s Integrating Public Policy Task Force (IPPTF) learned Monday.

That so-called “negative leakage” in other parts of the Eastern Interconnection would be the result of electricity price changes that very slightly favor natural gas over coal generation, analysis by the nonprofit Resources for the Future (RFF) found.

At the IPPTF’s Sept. 24 meeting, RFF’s Dan Shawhan presented the study, which modeled the impact of carbon pricing on emissions and prices in New York and neighboring regions based on expectations for 2025. The group used its own Engineering, Economic and Environmental Electricity Simulation Tool (E4ST) to project effects in New York and throughout the interconnection.

In terms of 2025 dollars, the study estimates an environmental benefit of $288 million per year, mostly from a slight reduction in emissions outside New York, and a net total benefit of $279 million per year.

Because New York will have no coal-fired capacity in 2025, less than a quarter of the estimated environmental benefit is from NOx and SO2 emission reductions, Shawhan said. Estimated SO2 damage actually increases slightly because a carbon charge would shift some emissions to locations that cause larger estimated health damage per pound emitted.

Excluding the positive environmental benefits, collective end-user costs in New York come in at $562 million per year, equivalent to $3.60/MWh, with a “somewhat smaller profit gain” for New York generators.

The study estimates a 0.9% reduction in generator CO2 emissions in the state and a 0.2% increase in in-state generation. RFF attributes a 1.1% reduction in New York power sector CO2 emission intensity primarily to equalizing the CO2 emission price applied to in-state fossil fuel generators both exempt from and subject to the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. A carbon charge would reduce damage from New York generator emissions by $17.4 million per year. With the RPS still binding in 2025, the study finds no change in the state’s volume of renewable generation due to carbon pricing.

The study estimates an LBMP price increase of approximately $20/MWh in zones A-E, $22/MWh in zones F-I, and $23/MWh in zones J and K, while the renewable energy credit price would drop from $45.88/MWh to $27.28/MWh, and the zero-emissions credit (ZEC) price would plummet from $13.64/MWh to zero.

Upstate nuclear unit revenue would climb under the model from $65/MWh to $67/MWh, while the RGGI price would rise slightly, from $11.28 to $11.90 per ton CO2.

Couch White attorney Michael Mager, who represents Multiple Intervenors, a coalition of large industrial, commercial and institutional energy customers, said: “If one were to rely on your study results to decide whether New York should do this or not, it would be tough to make that decision on a single-year snapshot, so I’m trying to get a feeling for whether your model is likely to produce consistent results over time.”

“I think of this as an approximation of the average effect over the multiyear period … however, it is not exactly the same as what we would get if we simulated each of those years,” Shawhan replied.

Zonal Allocation

The Brattle Group’s Sam Newell presented analysis on carbon revenue allocation — the process of crediting carbon prices back to electricity consumers. The analysis shows the implications of four alternative allocation approaches that NYISO had proposed and provides a spectrum of options along two competing allocation objectives: to align LBMPs with the marginal cost of serving load while avoiding major cost shifts among customers.

“As soon as you get into debating how best to allocate money, that’s a very difficult discussion,” Newell said.

Newell said transmission constraints into New York City represent one of the key challenges related to allocation.

“So if you add a carbon charge, you’d have a greater increase in LBMPs there than elsewhere, and that’s one of the things we need to account for… and how that can possibly be offset by different allocation approaches,” he said.

All the individual zone results in the study’s appendix reflect nodal modeling, he said. To the extent there are transmission constraints going into Zone J (New York City), the model tries to capture them.

But the model found the biggest constraint “by far” is really across NYISO’s Central-East Interface, “much more than it is going into southeast New York,” Newell said.

“We did the math, and not surprisingly, with the load-share approach, everybody in every zone, whether upstate or downstate or any part of those, gets about $10/MWh” in allocations, Newell said.

To levelize the net effect (what an LSE pays for the carbon component of the LBMP minus the allocated residuals), downstate zones would need to receive about $4/MWh more in allocated residuals than upstate zones, he said.

IPPTF Chair Nicole Bouchez, the ISO’s principal economist, said, “When we would go to do the allocations, there are only two things we can observe: one is the carbon component of the LBMP, and the other is how much money we collected from generators.”

The ISO cannot observe whether a carbon scheme attracted more investment downstate than upstate and thereby lowered capacity prices downstate, lower than the non-carbon component of LBMPs downstate, Newell said.

A carbon charge opens up a bigger gap between the upstate price and the downstate price, and the markets will tend to levelize the impacts somewhat as suppliers respond to and partially undo the price stimulus, he said.

“What are dynamic effects?” Newell said. “That’s the market responding to price signals.”

Seams and MER

Newell also presented analysis on seams, reiterating a presentation he made in April on applying carbon charge border adjustments to the ISO’s external transactions.

Newell backs the ISO in proposing to levy import charges and export credits in such a way that makes the effects of carbon pricing invisible to external transactions, with external resources competing on a “status quo” basis. However, if NYISO were to consider an alternative approach, levying charges based on the emissions associated with transactions, several key concepts would have to be addressed, Newell said.

“What is the relevant rate?” Newell asked. “Is it the average rate of their fleet? No, it is the marginal emissions consequences of taking a transaction from there. That’s how spot pricing is supposed to work — to create efficient marginal incentives in the operating timeframe. So they’re not average emissions; it’s the marginal emissions rate.”

One stakeholder questioned the study’s hypothetical resource shuffling that might result from a “status quo” approach to carbon pricing, saying the ISO has import limits and it’s probably impossible for all of the nuclear generation in PJM to flow in while all the fossil generation in New York state flows out.

“Yes, it can happen,” Bouchez said. “When you look at imports and exports today, in any one hour, it’s almost unheard of to see transactions only going in one direction … physically there are people importing and exporting at the same time on the same interface. What matters are the net flows, which we calculate as the net of the imports and exports.”

Tariq Niazi, ISO senior manager and Consumer Interest Liaison, presented a study summarizing the Brattle report, finding that a carbon charge would reduce CO2 emissions approximately 3% by 2030, causing only limited fuel switching, and that most emission reductions would result from dynamic effects such as renewable shifts, nuclear retention and price-responsive load.

Speaking of the need to reconcile various reports and their differing cost estimates, Niazi said, “Our focus is to get this NYISO analysis done between now and mid-October, when we plan to come back.”

Brattle will present the final version of its customer impact analysis at the next IPPTF meeting on Oct. 15 at NYISO headquarters, with an additional task force meeting possible in the interim.