By Michael Kuser

TROY, N.Y. — The state must put a price on carbon in its wholesale electricity market if it hopes to meet the aggressive timelines of the decarbonization goals set out in a new law, the co-author of NYISO’s carbon pricing study told stakeholders last week.

“If New York does not do this in the electric-sector engine that the law hopes to rely upon to decarbonize the economy, it’s tying two hands behind the state’s back,” Analysis Group’s Sue Tierney said on Oct. 22 in delivering a summary of the study to NYISO’s Installed Capacity and Market Issues Working Group (ICAP/MIWG). “You will not get the efficiency, or timing, or depth, or pace of change without having this electric system engine on acceleration to get it.”

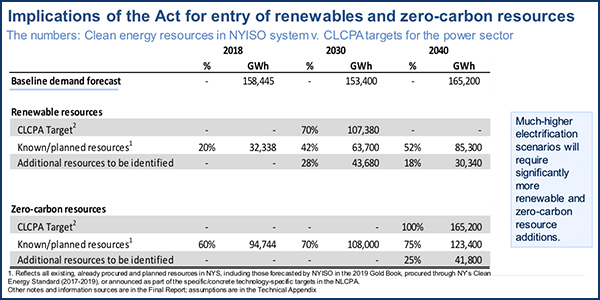

Delivery of the long-awaited study was delayed a couple months to perform additional analysis on the impacts of the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA), signed into law in July by Gov. Andrew Cuomo. Among other provisions, the law requires 70% of the state’s electricity to be generated by renewable resources by 2030 and the whole economy to be carbon-neutral by 2040. (See NYISO Study: Carbon Charge to Help NY Climate Goals.)

“It’s going to be really hard to meet the new goals in the CLCPA, even with a carbon price. It’s going to be really hard, so the state should be relying on every tool it can to get the job done,” Tierney said.

Implications of the CLCPA for entry of renewables and zero-carbon resources in New York | Analysis Group

NYISO stakeholders took a fine-tooth comb to the final version of the carbon pricing study at the ICAP/MIWG meeting, posing dozens of questions to Tierney.

“Is there a threshold size of the [decarbonization] solution that needs to come from carbon pricing, or is it linear, like you can have as little as 1% of it being accomplished through carbon pricing, or 99%?” asked Aaron Breidenbaugh, representing Consumer Power Advocates.

“I don’t think there’s an engineering or an economic answer to that because we’re going to be surprised, happily surprised, by a market solution,” Tierney said. “Introducing a carbon price will create a dynamic effect, which in turn will produce results later on, and the results will affect things that happen after that.”

Market Efficiencies

The report said the literature on organized wholesale markets indicates carbon pricing will produce a 1 to 3% efficiency improvement in the overall capital and operating costs of the wholesale electric system.

“Applying that range of market efficiency benefits to the above-market cost analysis, we estimate a benefit to New York consumers in the range of $280 [million] to $850 million, net present value, for a baseline scenario running from 2022 to 2036,” Tierney said. The baseline refers to the NYISO Gold Book forecast of baseline demand, she said.

“What is the 1 to 3% supposed to be capturing?” asked Howard Fromer, director of market policy for PSEG Power New York. “In a world that had the social cost of carbon reflected in LMPs, one would expect LMPs to trend higher to capture that cost in a marginal unit, to the extent that fossil is that marginal unit. I would expect that as that percolated through the electric system … you would see people doing things differently, being more active in efficiency opportunities as prices were higher. I assume some elasticities. … Is this 1 to 3% capturing that kind of benefit?”

Tierney provided an example: “If one did a long-term renewable energy credit procurement as the only approach to meeting the requirements of the CLCPA, then an owner of a fossil unit … might decide that the next dollars it might consider spending on operations and maintenance to keep that plant the most efficient one are not worth spending. The market would be telling that owner that it would be stupid to invest in such efficiency. This [1 to 3%] is meant to capture the other things going on.”

Mark Reeder, representing the Alliance for Clean Energy New York, said he assumed that carbon pricing would have negligible effects on energy efficiency, as residential retail prices would go down.

“There is no increase in energy conservation in homes from a program that results show the prices are in fact going down,” Reeder said. “Maybe you could have done an offset to your $280 million and go down another 15 [million dollars] and say it’s $265 million, but we keep forgetting the result … is customer prices go down. The customer impacts are quite near zero, but on net, the prices go down.”

Reeder questioned the premise of getting the 1 to 3% coming from the dispatch: “Most of the literature about going to deregulation was that it would increase efficiencies in terms of people’s investment decisions, in terms of their maintenance decisions. I would think the bulk of the 1 to 3% is in the investment decision to extend the life of your plant, to make your gas plant more efficient. None of those are dispatch efficiencies.”

Tierney disagreed. “There will be also dispatch efficiencies, along with the other types of efficiencies,” such as investments to make individual plants more efficient and others that reflect a shift of risk from consumers to owners of generation and transmission, she said. “So the dispatch efficiencies will be reflected in the new portfolio of resources [that] results from the new investment signals, including locationally in New York. Our 1 to 3% is meant to cover all of those types of things.”

Transmission Differentials

“We include in the value proposition that the carbon price would send signals for transmission as a result of a differential in LMPs, upstate and downstate,” Tierney said. “We also said that part of the value proposition here would be more direct signaling about the value of adding demand and supply resources in downstate New York, where most of the load occurs and where the prices would be higher.”

One of the benefits listed in the report has to do with transmission buildout, which NYISO has already documented as essential to New York meeting its aggressive goals, Fromer said.

“There is simply no way we’re going to make a dramatic dent in carbon reduction unless more transmission is built in the state,” Fromer said. “To what extent does the 1 to 3% benefit capture the difference of a likelihood of transmission buildout in a world where you’re moving $30 power to a $35 market, versus $30 power to a $55 market? How do you get the public to accept spending a billion dollars for a line that’s saving hardly any money?

“What is the logic that you get more transmission built from upstate to downstate unless you’re reflecting the carbon benefit of that transmission in the price — and is any of that in the 1 to 3%?”

Tierney said she didn’t think so. “Based on the literature review, that has not been called out as a specific issue. I think that is a powerful advantage of the NYISO’s carbon-pricing proposal, putting a price signal on transmission.”

Fromer said that raised the issue of whether the state would get more carbon reductions by just relying on REC contracts.

“One of the concerns with the [CLCPA] is … you might not get carbon reduction from some of the renewable additions upstate because the load being reduced would have been using renewables anyway, and you don’t have the lines to move the surplus power downstate,” Fromer said. “Even though you’re spending a lot of money, you’re displacing other pre-existing carbon-free energy.”

“I agree. … When we did our buildout scenarios and estimated the above-market costs that one might expect as a result of the CLCPA, which was the lump of money from which we said that you could expect to get 1 to 3% in efficiency savings, we included no transmission investment in that,” Tierney said. “We did include one scenario [that] assumed that all of the offshore wind dumped into New York City, so that higher cost is reflected in part in there.

“In order to actually get the carbon reductions, there has to be a demand forecast that reflects electrification of buildings and vehicles, including in downstate New York, where most of the state’s demand is located, and that has to include getting the power to where people live,” she said.