By Rory D. Sweeney

VALLEY FORGE, Pa. — PJM is considering a significant increase in the performance participation threshold for participants in its regulation market.

The current minimum participation threshold of 40% may be increased to 75%, RTO officials told the Operating Committee meeting last week. Each unit is evaluated for participation based on its average scoring over the past 100 hours of regulation service on three components: precision, accuracy and delay.

American Electric Power’s Brock Ondayko said increasing the participation thresholds could have a major impact on the number of megawatts available to respond, noting that steam units, which make up the vast majority of RegA participants, average a 75% performance score.

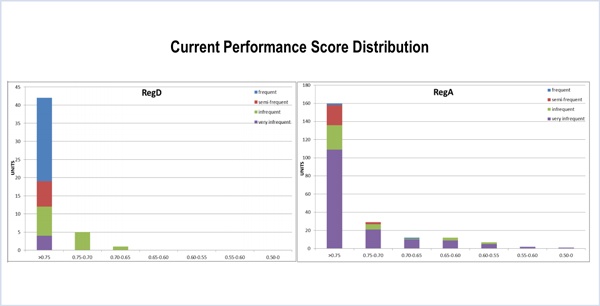

As part of a quarterly report on regulation performance, PJM’s Eric Hsia provided a graph of participants’ average performance and frequency of participation. The results provided a stark contrast between participation in RegD — a dynamic regulation signal meant to stabilize constant frequency deviations — and RegA, a signal that is sent every four seconds.

Regulation-capable units that accept the offered price for participation are expected to align their output with the signals they receive from PJM. The RTO’s data show that, while there is far more participation in RegA, participants in RegD participate far more often.

Responses Hard to Predict

PJM said it is seeing wide variability in primary frequency response between evaluated frequency events, with many generators either not responding, withdrawing responses or responding in the opposite direction — decreasing output, for example, when frequency declines. Additionally, a “significant portion” of primary frequency response is coming from load, which can’t be predicted or controlled, PJM’s Danielle Croop said.

It’s a “roll of the dice” every time to see what’s going to happen, she said. Croop presented several graphs of units’ responses to recent frequency response events that showed the units either not responding, stopping their response, not providing sustained response or responding in the opposite direction.

One potential cause of the erratic performance is that a unit’s “operating control mode” is following some other indicator and not in droop mode allowing them to respond to frequency deviations, she said. Units that don’t respond at all might be operating in modes or with governor settings, that don’t allow for response — or have their governors turned off altogether, she added.

About 69% of frequency response in 2016 has come from coal-fired units, Croop said. In response to a question from Ondayko, she speculated that the participation level of natural-gas-fired units at just 19% was likely due to three factors:

- Units must be on the grid to provide frequency regulation, so fast-response natural gas units that run sporadically often won’t have an opportunity to get involved;

- Control systems might be “squelching” or preventing the response; or

- Units might be operating so close to their maximum capacity that they don’t have much room to adjust.

Units that are providing regulation are not expected to also provide primary frequency response, Croop said, and so aren’t calculated into PJM’s expected performance.