Oregon Gov. Kate Brown can expect a raft of policy recommendations to land on her desk this spring prescribing how her state can build a comprehensive — and equitable — electric vehicle charging network.

But a number of the proposals will be difficult to implement — at least in the short term, according to one consultant working with the state’s Transportation Electrification Infrastructure Needs Analysis (TEINA) Advisory Group.

Established by Oregon’s Department of Transportation (ODOT), the group — comprising representatives from investor- and municipally owned utilities, municipalities, environmental organizations, labor groups, AAA and General Motors — must provide the governor with an EV charging infrastructure study by June.

“I just want to acknowledge that we won’t be able to solve all of the problems coming out of this study,” Rhett Lawrence, policy manager with consulting firm Forth, said Tuesday in presenting a set of draft recommendations during a virtual meeting of the TEINA group.

Oregon Senate Bill 1044, passed in 2019, established objectives related to the adoption of light-duty zero-emission vehicles (ZEV), including a goal of 250,000 ZEVs registered by 2025. The bill additionally set targets that ZEVs comprise 25% of all registered vehicles and 50% of all new vehicle sales in the state by 2030, with the sales target rising to 90% in 2035. The state currently has about 32,000 registered ZEVs, well short of SB 1044’s 2020 target of 50,000 vehicles.

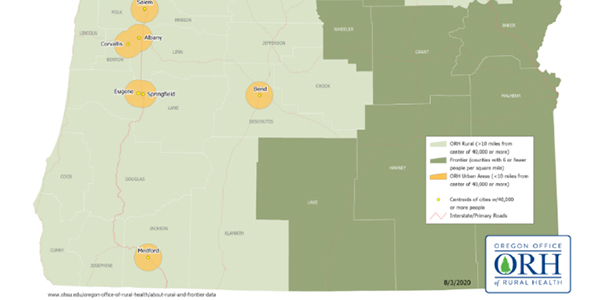

A key challenge for Oregon’s EV adoption goals will be building sufficient infrastructure in areas classified as “Rural” (light green) and “Frontier” (dark green). | Oregon Office of Rural Health

As in other states, Oregon’s EV adoption rates evince a sharp urban-rural divide. While 65% of the state’s residents live in areas classified as urban, nearly all EV ownership is concentrated in those zones, confronting policymakers with the challenge of how to build reliable EV infrastructure to support people who live and travel through the state’s sparsely populated regions. Within urbanized areas, the state faces the additional problem of how to make EV chargers readily available to low-income residents and city dwellers living in multifamily buildings where off-street charging is unavailable.

Because of those complexities, Lawrence counseled the TEINA group to divide its policy recommendations into three categories based on the degree of difficulty for implementation: Enable, Accelerate and Drive. The recommendations are the product of a series of “listening sessions” with residents and stakeholders from across the state.

Putting the User First

Topping the lowest-difficulty category — “Enable” — is the recommendation that Oregon policymakers develop standards that create a consistent experience for EV drivers even as they use different charging network platforms throughout the state.

“This is something that came up in almost every listening session,” Lawrence said.

That consistent user experience would extend to expectations around the reliability and redundancy of chargers.

“You need confidence that anywhere you go in the state that you find a charger that will work,” Lawrence said. He suggested that once the state develops the standards, it could build them into the requirements of any state-funded grant programs intended to help finance construction of charging stations. Charging service providers could themselves begin to work together to create uniform standards, he added.

Another recommendation would see the Oregon Public Utility Commission and municipally owned utility governing bodies “enable and encourage” utilities to use ratepayer funds to build the underlying transmission infrastructure needed to support EV charging networks.

“EV make-ready funding should be made available to provide adequate electrical infrastructure up to and past the meter to install EV charging at places such as workplaces and multiunit-dwellings (MUDs),” the draft document said.

Kelly Yearick, program manager at Forth, suggested that Oregon could use revenues from its Clean Fuels Program to fund DC fast chargers (DCFCs), the Level 2 chargers in areas of high population densities to allow for charging by people living in MUDs.

Yearick also said utilities might need to alter rate designs to reduce demand charges — the flat fees utilities charge to recover costs from investments — for charging stations in areas that will see lower use. Those fees compromise the economics of charging stations in rural areas, where a smaller pool of potential EV drivers need a relatively larger proportion of stations because of the distances typically traveled in those areas.

Other “Enable” recommendations include:

- incentivizing charging stations in highly traveled corridors through low-interest state loans;

- directing local jurisdictions to develop or follow state guidelines to streamline charging station permitting;

- developing EV charging education programs “to improve the general public’s awareness of this infrastructure and enhance the user experiences at EV charging stations”;

- developing uniform guidelines on EV charging station signage and placement;

- coordinating with local jurisdictions to develop public-private partnerships for charging electric bikes and scooters.

Getting to the ‘Hard Work’

The “Accelerate” category consists of policy recommendations “that could speed up the deployment of electrification infrastructure with medium difficulty of execution and implementation for the key players over the medium term.”

Included is a recommendation that the state offer incentives or direct grants for public charging stations, particularly in rural and low-income areas. Lawrence pointed out that some charging stations will face power supply issues, especially in rural areas where the distribution system may not be equipped to handle the load. “State funding can help bridge that gap in how you deal with power supply issues,” he said.

A second recommendation in the category calls for the state to adopt building requirements that require a minimum built-in electrical capacity for all new developments as well as “reach codes” that allow local jurisdictions to exceed state mandates.

A third recommendation would see the state direct municipally owned utilities to invest in DCFC projects.

The “Drive” category includes longer-term recommendations considered more difficult to implement, including state funding for EV charging infrastructure on state-owned property such as parks or workplaces. Another recommendation would see the state requiring a certain percentage of parking spots be EV-ready by an undetermined date.

“We need to acknowledge that’s easier said than done,” Lawrence said, noting that the funding structure for such a program is still uncertain.

The TEINA Advisory Group will review a final draft study document containing the recommendations at a public meeting on May 11.

During Tuesday’s meeting, ODOT Program Manager Mary Brazell pointed out that the group will be taking on additional follow-on studies, including for hydrogen fuel cells and electric bikes.

“TEINA isn’t the end; it’s just the beginning of where we are, and we hope to engage with you as we complete that [infrastructure] document, but beyond as well, when we really get to the hard work, which is implementing this,” Brazell said.