A draft study on carbon pricing in Hawaii suggests that an appropriately structured carbon tax and monetary redistribution program would lower GHG emissions, provide households with a dividend and not overly hamper the state’s economy.

The University of Hawaii Economic Research Organization (UHERO) prepared the report for the Hawaii State Energy Office. Entitled Carbon Pricing Assessment for Hawaii: Economic and Greenhouse Gas Impacts, the state’s first comprehensive carbon pricing study examines four scenarios for taxing carbon in Hawaii.

Under the first scenario, the state would tax polluters $70/metric ton (MT) for carbon dioxide emissions, the social cost of carbon (SCC) calculated by the Obama administration’s Interagency Working Group on the Social Cost of Greenhouse Gases in 2016.

A second scenario would see the state charge $1,000/MT based on the state’s 2045 carbon neutral goal.

The third and fourth scenarios repeat the first and second scenarios but include a carbon tax revenue dividend to be paid to households.

Both taxes would be introduced gradually, reaching their full levels by 2045. The $70/MT plan is projected to result in a long-term GHG reduction of 25 MMT (million metric tons) by 2045, while the $1,000/MT plan would reduce emissions by 150 MMT.

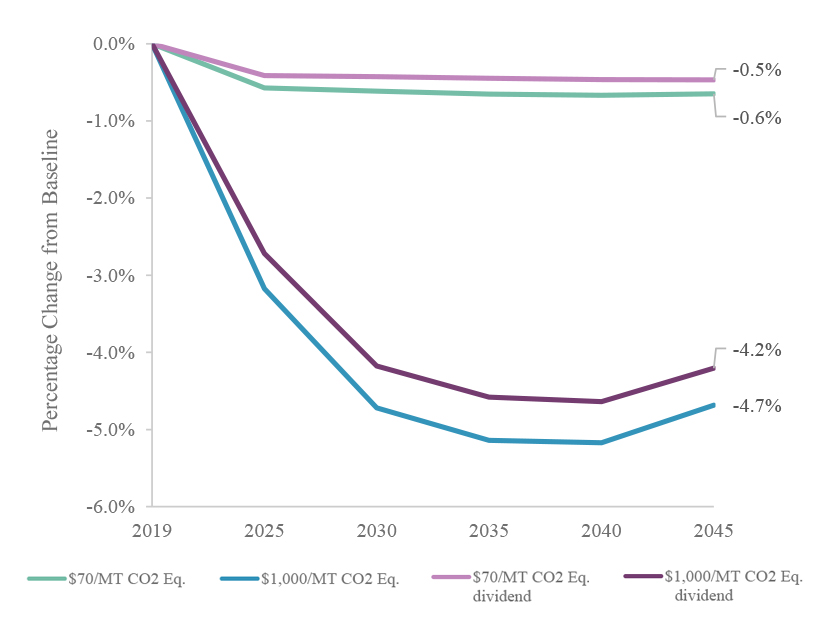

All four tax schemes would cause a dip in economic activity over the long term relative to a baseline scenario with no carbon tax. “These declines are relative to a baseline of growing [Gross State Product] … Thus it is not a decline from the 2019 economy, but rather represents a slower growth pathway,” the study said.

The $70 plan would reduce the “total output” of the economy by 0.6% by 2045, falling to 0.5% with the inclusion of a dividend program. The $1,000 plan would cut economic output by 4.7%, or 4.2% with the dividend.

While imports and visitor spending would see modest downturns, Hawaii’s exports would take a roughly 5% hit under the $70 plan, rising to 30% under the $1,000 plan. “There is an overall loss of competitiveness for Hawaii goods and services” under either plan, the study said.

Energy prices would also be impacted, with the $70 plan raising gasoline prices by 63 cents/gallon and natural gas prices by 35 cents/therm, while electricity prices would remain unaffected. The $1,000 plan would drive up gasoline prices by a whopping $9/gallon, natural gas by $4.90/therm and electricity by 3 cents/kWh.

The electric vehicle sector would reap benefits because of increased gasoline prices. By 2045, EV vehicle miles travelled would increase by 20% under the $70 plan and more than double under the $1,000 plan when compared to the baseline projection of no carbon tax.

Household Impacts

“One of the things we were particularly interested in here is understanding how a carbon price would affect different kinds of households by income level,” Makena Coffman, the study’s principal investigator, said during an April 7 presentation of the study to the Hawaii Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation Commission.

In examining energy use based on household income, the study’s authors found that the top 20% of earners consume 32% of Hawaii’s gasoline, 31% of its natural gas and 26% of its electricity, whereas the bottom quintile consumes 9.6%, 12% and 14%, respectively. The study concluded that a flat dividend rate for households would be progressive because, as Coffman said, “It would be high-income households who pay into the tax more.”

The study also found that by 2045 the $70 plan would provide the state with $610 million in annual revenue, compared with $2.8 billion under the $1,000 plan. Distributed equally, that would provide about $1,000 and $3,000 annually per household, respectively.

Without dividends, both plans would see net spending power drop by a few percentage points depending on household quintile. With dividends, the $70 plan yields a marginal increase in net spending power, while the $1,000 plan results in a marginal decrease. The dividend under the $1,000 plan “is not enough to offset the impacts of the shrinking economy,” the study said.

The study makes a case for implementing a direct carbon tax instead of pursuing other policies to mitigate GHGs, contending that the economy-wide approach “lowers the cost of reducing GHGs because it captures a range of GHG reduction opportunities while harmonizing sectoral interactions.”

“Often regulatory policies are less effective because they fail to address total emissions directly and instead target a proxy for emissions (e.g., vehicle miles traveled) or the rate of emissions (e.g., emissions per unit of electricity generated),” the study said. “Carbon pricing also addresses both new technologies and the ongoing use of fossil fuels … Carbon pricing can be implemented economy-wide, serving to capture GHG reduction opportunities in multiple sectors and harmonize the marginal cost of abatement among sectors.”

If implemented, the $70 plan would lower GHGs by 13% and the $1,000 plan by 70% when compared to the no carbon tax baseline. But the study notes that “[a]s the carbon price approaches $300-$400/MT CO2 [equivalent] … the effectiveness of the carbon tax declines as fewer GHGs are reduced per dollar of tax.”

“There is little economic argument for Hawaii, or any other state, to unilaterally adopt a very high carbon price,” the study concludes. “Hawaii’s per capita emissions are double the global average — motivating a responsibility to play a role in global GHG mitigation.”

The authors contend that a carbon price in line with the Obama administration’s SCC assessment would encourage renewable development and “dissuade fossil fuel burning in power plants and vehicles,” going “a long way” in reducing Hawaii’s contributions to global GHGs.

“At the federal SCC price, returning revenues in equal shares to households would benefit lower-income households relatively more as well as make all of Hawaii’s households economically better-off,” the study said.

Reaction

After the April 7 presentation, the commissioners offered little comment on the study other than expressing satisfaction with the scope. State Rep. Nicole Lowen (D) said that the study’s energy use estimates represented statewide averages that might obscure regional differences.

“Can you speak to what the difference might be between residents in more rural areas who have to spend significantly more on gasoline, for example?” Lowen said. “I feel like it’s important to think about how we look at an average, but it doesn’t account for the differences between islands or between rural and urban.”

“That was totally out of scope to [this study], but I think it’s really important,” Coffman said. “That is the next step. How do you take this information and make it spatial.”

Hawaii Sierra Club Director Marti Townsend pointed to another area of potential inequity.

“It is a little unfair to me to set a price on carbon and have the general public pay for it when we have large corporations that disproportionately benefited from the use of carbon and actually delayed the transition to clean economies,” Townsend said. “The state of Hawaii is facing very expensive climate mitigation measures, and there is no reason why the fossil fuel companies cannot also participate in helping us address this.”

Coffman agreed, explaining that the specifics of implementation were beyond the study’s focus but were important for the success of either plan.

UHERO will release the final study on April 23.