A UC Berkeley study found that high electricity prices in California, New York and most of New England could undermine efforts to electrify transportation and homes, while the “social marginal costs” of pollution from natural gas and gasoline remain unaccounted for, making the fuels seem a less expensive option to consumers.

The study was authored by UC Berkeley Prof. Severin Borenstein, a member of the CAISO Board of Governors, and UC Davis Prof. James Bushnell, a member of the ISO’s Market Surveillance Committee.

A “challenge to the process of electrification that is obvious to economists, but surprisingly less prominent in policy discussions, is overcoming relative retail price disparities between the three fuels,” Borenstein and Bushnell wrote. “For many U.S. residents, electricity can be the most expensive of the three energy sources.”

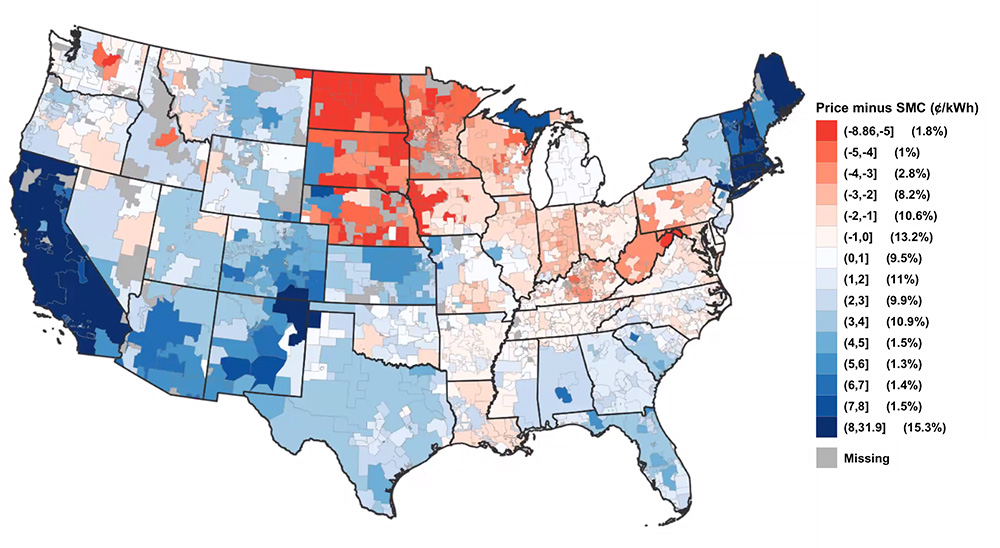

In a webinar to discuss their paper Tuesday, Borenstein said the costs of fuel sources should include pollution and other societal impacts. Electricity is too expensive under such a formula in California, New York City and much of New England, and underpriced in the upper Midwest and other regions, the research found.

In California, where renewable energy sources account for about one-third of in-state generation and more than 30% of imports, electricity supplied by large investor-owned utilities is “about three times higher than social marginal cost,” Borenstein said. Electricity is also priced well above social marginal costs (SMC) in parts of New York, Connecticut and other New England states, he said.

In contrast, states such as North Dakota, South Dakota and Minnesota have electricity costs that are low compared with the pollutants released by coal and other fossil fuel generation, the research determined.

“We find that significant pricing distortions arise in electricity, where prices can be up to four times SMC in some states, and 25% or more below SMC in other states,” Borenstein and Bushnell wrote.

Those areas are outliers, however. Much of the nation has electricity and natural gas prices that generally reflect their true costs.

“A large part of the country actually is plus or minus a couple of cents from social marginal cost prices,” Borenstein said.

Getting Prices Right

The findings are important because energy prices influence consumer choices, Borenstein said.

Mispricing fossil fuels can impede decarbonization, he suggested.

“When you get that price right [using MSC], when consumers go to make consumption decisions, they’re seeing a price for a decision that actually reflects the cost their decision would impose on society,” he said.

“If we get all of the prices to reflect social marginal costs, [when consumers are] choosing between energy sources — say, between natural gas and electricity — for heating their house, they will be making that decision based on the energy costs that actually reflect the full cost of each energy source,” Borenstein said.

Another problem is that electrification efforts may enlarge the price gap between clean electricity and fossil fuels in states such as California where electricity is mispriced.

“While low-carbon electricity production sources have rapidly declined in costs, most analysts predict that ‘deep’ decarbonization will require costly investments in battery storage, transmission, and more exotic and expensive technology solutions, such as hydrogen for long-duration storage,” the paper said.

For economists, Bushnell and Borenstein wrote, “the logical solution to such a pricing gap would be carbon pricing either through a tax, cap-and-trade, or some other mechanism. This solution is complicated by the fact that there are existing taxes and other pricing distortions that have already caused fuel prices to deviate from marginal costs.”

In California, natural gas accounts for 86% of space and water heating, though efforts are underway to encourage residents to switch to electric heat pump space and water heaters. (See Calif. Energy Commission Adopts 2022 Building Code.)

“For both space heating and hot water heating, changing the volumetric prices of electricity and natural gas from their current levels to SMC would greatly alter the economics of the energy choice for these primary residential uses,” the authors wrote. “In both cases, current energy prices tilt strongly in favor of natural gas, but pricing at SMC would effectively eliminate that difference.”

For cars, “gasoline … is largely underpriced relative to SMC, a gap that is most extreme in dense urban areas most vulnerable to local air pollution,” the authors said.

California’s governor issued an executive order last year requiring all new passenger cars and trucks sold in the state to be electric vehicles or other zero-emission vehicles by 2035. The state is far from meeting that goal, however, and must exponentially increase EV sales.

That could change with accurate energy prices, Borenstein and Bushnell determined.

“Lower fuel costs are supposed to be one of the big advantages of electric vehicles, but at current rates in California — where we find gasoline is priced below SMC in most locations and electricity is priced well above SMC — we find the fuel cost advantage of EVs would increase by about $500 per year on average if each fuel were priced at SMC.”