RICHMOND, Va. — Rachel Pachter was treated like a rock star at the Business Network for Offshore Wind’s International Partnering Forum here last week. In May, Pachter, chief development officer for Vineyard Wind, successfully led efforts to win the first federal approval for a commercial-scale offshore wind project.

For Pachter, the victory was two decades in coming: She also was part of the Cape Wind team, whose plan for a wind farm in Nantucket Sound died in 2017 following a 16-year battle with residents concerned about the visual impact and complaints it would pose a threat to offshore navigation, marine life and birds.

The second time around, Pachter and Vineyard Wind — a joint venture between Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners and Avangrid Renewables (NYSE:AGR) — had an important ally. “The Vineyard Wind project … actually went into a BOEM [Bureau of Ocean Energy Management] auction with a community partnership with a nonprofit on Martha’s Vineyard called Vineyard Power. That community partnership has been key to our success,” Pachter said during a panel discussion moderated by attorney Ted Boling of Perkins Coie.

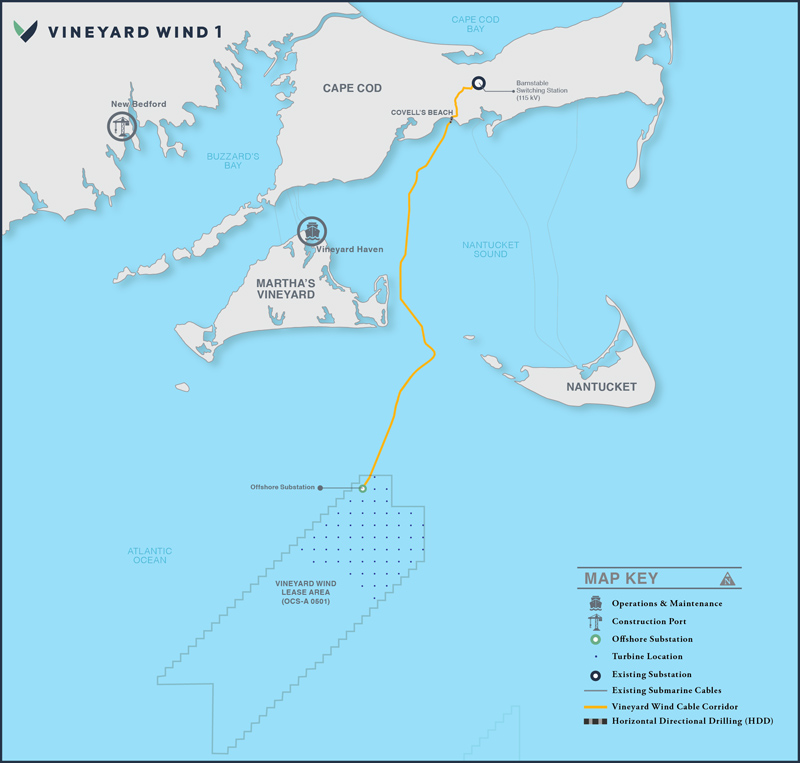

“We’re very lucky that Martha’s Vineyard is really interested in renewable energy. And we’ve been able to sort of harness that relationship,” she said, adding that the company also developed “an early relationship” with the town of Barnstable, Mass., where the project’s transmission cables will reach land.

“So we’ve built these partnerships, and we’ve tried to make them … about how to move what we need forward with what other folks need to move forward. … That was a huge part of our success: We saw huge support for our projects, as we went through multiple [National Environmental Policy Act] processes … and [through the environmental impact statement]. And that is because we put a ton of effort into that. … We’re not going to get everybody. But we do need people to stand up for these projects, for sure.”

‘Getting Everyone into the Same Space’

“We know how to build offshore wind; there are very few questions left about the technology,” said Kris Ohleth, executive director at the Special Initiative on Offshore Wind, a project of the University of Delaware’s College of Earth, Ocean and Environment. “But getting everyone into the same space, and to that same place of the shared societal benefit that offshore wind can bring, while maintaining existing ocean uses — that for me is paramount as we look at offshore wind through the next decade. Those are the real challenges.”

Pachter stressed the importance of transparency and education in winning over stakeholders.

“People are always calmer when … they have knowledge, right?” she said, comparing it to a patient dealing with a medical issue. “As soon as I explain it to you, you always feel a lot better. It’s the same thing. If somebody explains to you how the grid works … I feel like you are instantly less freaked out. … [Developers must] refine your message [in response to] questions, and … figure out the best way to explain it.”

Patience is required, said Jennifer McCann, director of U.S. Coastal Programs at the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography. She is also director of extension programs for the Rhode Island Sea Grant College Program, one of 34 Sea Grant programs, which work with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“Our Northeast Sea Grant programs, in particular, have been urged by our stakeholders — by our communities and fishing entities — to play a leadership role in communicating information related to offshore wind, as well as ensuring that their knowledge and questions are [being incorporated] into the process, and also [ensuring] that their questions are being heard and responded to. Even if it might be the 200th time that it’s being asked in a public forum, it’s important to respond just like it’s the first time.”

The Northeast Sea Grant Consortium — Sea Grant programs in Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut and New York — are funding applied research to ensure “that our stakeholders have the best available science and best management practices to engage in efforts related to offshore wind,” McCann said.

Pachter said research being done for OSW environment impact statements and construction and operation plans can generate some goodwill, citing developers’ spending on technology to track whales.

“The North Atlantic right whale is being studied in areas that weren’t studied before; it’s being studied more than it was being studied before,” she said. “One of the real issues with the North Atlantic right whales is knowing where they are. … Knowing where they are would benefit our projects and benefits the species. It benefits the lobster folks who were also struggling a lot with their ability to fish when they don’t know [when] the whales are there.” (See related story, Nantucket Residents File Lawsuit Against BOEM to Protect North Atlantic Right Whale.)

Tradeoffs in the New York Bight

Scott Lundin, head of U.S. permitting and environmental affairs at Equinor Wind US, described his company’s efforts to work with the commercial shipping and fishing industries in the Empire Wind project south of Long Island. Input from the commercial fishing industry and other maritime interests resulted in the removal of more than 900,000 acres from consideration in the New York Bight as well as the development of proposed transit corridors for any future leases. (See Stakeholders Differ on OSW Leases in New York Bight.)

“The Port of New York and New Jersey is extremely important for the economic health of the region, and we need to make sure that Empire Wind is developed in a way that doesn’t disturb [commercial shipping] at all,” Lundin said.

The project’s mitigation also must account for the presence of marine mammals in the New York Bight year-round.

Lundin said the company also is considering an open area at the northwestern end of the lease, where the squid industry operates. “The way that they operate is … they follow the fish … and it can get very chaotic from time to time, depending on how hot the fishing is.”

The idea arose at a workshop with fishermen in Philadelphia a couple years ago. “We explained to them the different types of constraints and considerations that we have to think about when we’re trying to establish [turbine] layouts. We put maps on the wall; we invited people to take markers and draw,” Lundin said. “[We asked them], ‘If you were going to design a layout with those kinds of considerations, how would you put turbines around this triangular shaped development area?’ It was a very engaged workshop.”

That kind of in-person interaction became impossible during the shutdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, he lamented.

The pandemic also complicated the work of Lyndie Hice-Dunton, shortly after she became executive director of the Responsible Offshore Science Alliance in February 2020. “I went to the Maine Fisheries Forum, and then we shut down.”

It wasn’t all negative. Having to turn to remote communications “broadens your audience,” she said. “Our advisory council meetings are open to the public. We have people from the West Coast and all sorts of other places that are joining in and participating. But you miss that face-to-face interaction. You miss those conversations over a break where you can [say], ‘Hey, you know, I heard your concerns.’”

‘Multiuse’ Plans

It was Ohleth who titled the panel discussion “What’s Love Got to Do with it?” She said it was inspired by the “Virginia is for Lovers” tourism ads.

“Really, it was a little bit cheeky at first … a cheap ploy to get people to come in the room,” she joked.

But she said she also wanted the panel to discuss “how we’re using empathy and a collaborative approach and an open sense of curiosity [in] the process. I know in my experiences the best outcomes have really come from when I was leading with that spirit. … It just seems like those types of principles — ones that are more open and spacious — are ones that are going to bring us to have more success and to reach our 30-GW target by the end of the decade.”

McCann noted that some European governments are requiring that multiple uses be integrated into the siting and operation of offshore wind — a higher bar than merely requiring that developers and other ocean users tolerate each other. “Multiuse is to look at the synergistic relationships between resource activities, whether it be offshore wind and aquaculture, or offshore wind and research or tourism,” she explained. “I don’t know if we’re ready yet in the United States for multiuse, but I think our job as a university … is to consider multiple views and see if we can start a conversation.”