New Jersey is looking to jump-start the introduction of electric school buses in the state with millions of dollars in bus purchases — including a proposed $45-million pilot program in 18 school districts — along with guidance from private contractors that successfully introduced EV buses in other states and are saying the state needs to think big.

The proposal, soon to be introduced in the legislature, would offer a more aggressive approach than an existing, $10 million pilot proposal to fund three test projects, A1819, Sen. Patrick J. Diegnan Jr. (D) told an Oct. 13 forum on how to introduce electric buses into New Jersey. The earlier bill passed the Assembly on a 57-14 vote and is now before the state Senate Economic Growth Committee.

The event focused on providing key stakeholders with insights on the experiences of school districts and private bus companies that have introduced electric buses in other parts of the country, and the challenges facing New Jersey as it seeks to follow suit.

Diegnan’s new proposal would create a three-year pilot that would require three of the 18 school districts in the program to be located in environmental justice communities. A primary goal of the program would be to provide data on the use and efficiency of electric buses, which could then be used to promote electrification to other school districts, said Diegnan, who was also a sponsor of the earlier legislation.

“By doing this demonstration project we’re going to know how long does the battery last. Is there a problem with maintenance? What’s going to happen when the air conditioning is on in the summer? Is that going to affect it?” Diegnan said. “So rather than guessing where should we have the charging stations, this program will really put in place reliable information that we can use to move this forward.”

Diegnan said he hopes to get the bill introduced and passed by December, and the pilot program ready to start in the fall of 2022.

New Jersey had 15,703 school buses in 2019, none of them electric, and no electric buses have been registered with the state since, according to information from Atlas Public Policy. Only 1% of the nation’s 480,000 school buses are electric, according to the World Resources Institute (WRI), which helped organize the forum with the Electrification Coalition.

Aiming for Large Scale

Several speakers with experience introducing electric bus programs in other states encouraged New Jersey to move quickly and boldly, saying that the technology already has shown its worth elsewhere in the country. That approach will help overcome challenges to bus electrification, which they said include the difficulty of creating new infrastructure, adjusting to new technology and overcoming the sticker shock of high-priced zero-emission buses.

“What you want to think about are ways to encourage school districts to scale their electrification efforts” and think bigger, said Matt Stanberry, managing director of Highland Electric, a Massachusetts-based provider of turnkey electric fleet solutions, such as electric bus fleet “subscriptions.” “What we really want to be thinking about is creating seeds for electrification at scale.

“If you come in with a mindset of ‘I’m going to start with a single deployment,’ you’re sort of dead before you start,” Stanberry said. “You’ve got to be thinking about how do I set myself up to enable that scale, so I’ve got a plan for it? How do I limit the number of times that I’m breaking ground, busting up concrete, to lay in infrastructure?”

Jim Woods, director of business development for First Student, which provides student transportation to school districts, said that the urgency is so great that companies like his need to think in grander terms. The company has committed to electrifying 20,000 buses, more than half its fleet, over the next 10 years.

“Doing one or two buses here and there, you know, up to five buses, which is becoming more and more easy to do, is a good start,” he said. “But it’s not the way that we’re going to get there. We need to do this on a large scale.”

Grants Totaling $20 Million

Converting to electric buses is one plank of the New Jersey effort to get 330,000 electric vehicles on the road by 2025 and reach 100% clean energy by 2050. The state is mid-way through enacting a rule proposal to encourage the creation of medium- and heavy-duty EV charging stations that would service electric buses and medium- and heavy-duty trucks. (See: NJ’s EV Charger Rules Face Scrutiny.)

Electric school buses are key to the state’s effort not only because they help fight climate change and cut children’s exposure to the pollution generated by diesel engines, but also because they are well suited for the task, said Justin Balik, WRI’s senior manager for state policy for transportation. The limited range of electric vehicles, a primary concern for other types of transportation, is less of a factor on school routes, he said.

“Electric school buses can operate in 90% of the routes that are out there,” Balik said.

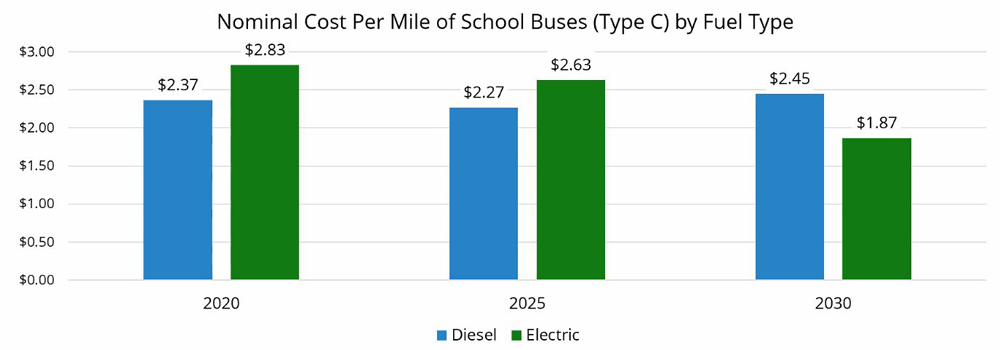

Electric school buses will become increasingly cost-competitive with traditional diesel vehicles over the next decade. | Atlas Public Policy

Electric school buses will become increasingly cost-competitive with traditional diesel vehicles over the next decade. | Atlas Public PolicyWith transportation accounting for about 42% of carbon emissions in New Jersey, the state has placed a high priority on reducing those emissions via funds from the state’s portion of the Volkswagen Settlement and the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). The state awarded $100 million, in large part to transportation, from the two funds in January, including $6.5 million for 17 school buses. (See NJ RGGI Spending Focuses on Transportation.)

Peg Hanna, assistant director of the air monitoring and mobile source programs at New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), told the forum that the state will soon announce another $20 million for electric school buses and trucks. Offering a contrast to the widespread perception that electric vehicles of all types are prohibitively expensive, Hanna said that “the projections show that we are expected to reach cost parity — a total cost of ownership parity — by 2025.”

A report released in March by Environment New Jersey and NJPIRG, a public interest advocacy group, said although the $312,000 price of a new electric bus is close to three times more than a new diesel bus, the lower fuel and maintenance costs for an electric vehicle would mean that school districts would save between $80,000 and $130,000 over the 16-year life of each school bus. (See: Environmentalists Call for Faster Transition to Electric Buses in NJ).

The fuel cost per mile for an electric bus will drop from $2.83 in 2020 to about $1.87 in 2030, at which point it will be cheaper than the cost of diesel, about $2.45 per school bus mile, according to information from Atlas Public Policy.

Hanna added that the transition to from diesel to electric school buses must be a collaborative effort.

“Converting to electric school buses and electric vehicles is not something that New Jersey government agencies are going to do solo,” she said. “We really need a combination of stakeholders, and a combination of approaches if we’re going to get there.”

Helping School Districts Jump In

Making it happen requires vigorous community support for school districts and the willingness to make tough decisions that will involve a sizable, upfront investment, said Stanberry of Highland Electric. The company has projects in development in 20 states, including a contract with Maryland’s Montgomery County Public Schools, which will lease 326 electric school buses over four years. (See: Schools’ ‘Budget Neutral’ Bus Deal Could Accelerate BEB Growth).

Financial support from the state is also essential, said Jacqueline Piero, vice president of policy for Nuvve, a San Diego provider of vehicle-to-grid technology that allows EVs to send electricity back onto the grid. One way to make electric buses more financially attractive and acceptable to school districts is to shape the way that support is delivered, she said.

State officials should structure incentive programs around vouchers or rebates, which enable districts to receive reimbursement for investing in electric buses, rather than grants, Piero said

“We found that it’s not just giving schools money; it’s how you give them money that actually can make a huge difference in whether or not they’re able to pull the trigger and electrify,” she said. “We are finding that schools are much more able and willing to engage when they see a more direct process.”

Programs in which the state provides a rebate after the purchase is made are a more direct way to get funds to school districts, but they need to have the money to spend up front, said Piero, who also encouraged the state to produce “step-by-step guides” that explain to school districts how to electrify their fleet and avoid pitfalls. Otherwise, she said, “they can end up with incompatible systems that they’ve cobbled together.”

Woods, of First Student, said school districts and bus companies need to look to the future and ensure that the steps they take early on in an electrification process, especially when it comes to infrastructure, will serve them well as they grow. He noted that to ensure that First Student can secure enough clean electricity to power its buses, the company has partnered with NextEra Energy, which invests in clean energy infrastructure and utilities.

“Infrastructure is one of the biggest challenges,” Woods said. “Putting five buses on a site with a $1,500 charger is not too difficult. Doing 50 buses is entirely a different story.”

He said the company’s purchase of 260 buses from Lion Electric, a California electric bus manufacturer, to put into service in Quebec, Canada, reflects the economies of scale needed to make electric buses viable.

“School districts have limited budgets,” and companies like his need to help them electrify their bus fleets “at a near diesel equivalent cost,” to make the task successful, he said.

“If we don’t have the volume to drive down pricing, then buses are going to continue to be expensive,” he said. “But somehow we’ve got to get beyond the hurdle of that initial expense.”