Oregon’s Environmental Quality Commission (EQC) voted 3-1 Thursday to approve rules setting declining caps on greenhouse gases from fuel suppliers, cutting their emissions 90% by 2050.

A key pillar of the state’s growing climate change efforts, the Climate Protection Program (CPP) comes after Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) staff worked for a year-and-a-half engaging in listening sessions, technical workshops, town hall meetings, committee meetings and extensive rulemaking proceedings before proposing the final rules.

“I’m just shocked we got to this point,” EQC Vice Chair Sam Baraso said ahead of the vote. “At the time when you all laid out your schedule, I know I was like, ‘That is not going to happen, and there’s no way it’s going to happen,’ and so I’m incredibly, incredibly impressed.”

DEQ Director Richard Whitman said that while the CPP is “not by any means the only piece of the puzzle,” it represents the “glue that kind of knits together” all of Oregon’s climate efforts and “gives us a clear pathway to a cheaper, cleaner energy future.”

Covered by the Cap

The CPP consists of two components: a cap program covering fuel suppliers and a best available emissions reduction (BAER) program for stationary sources.

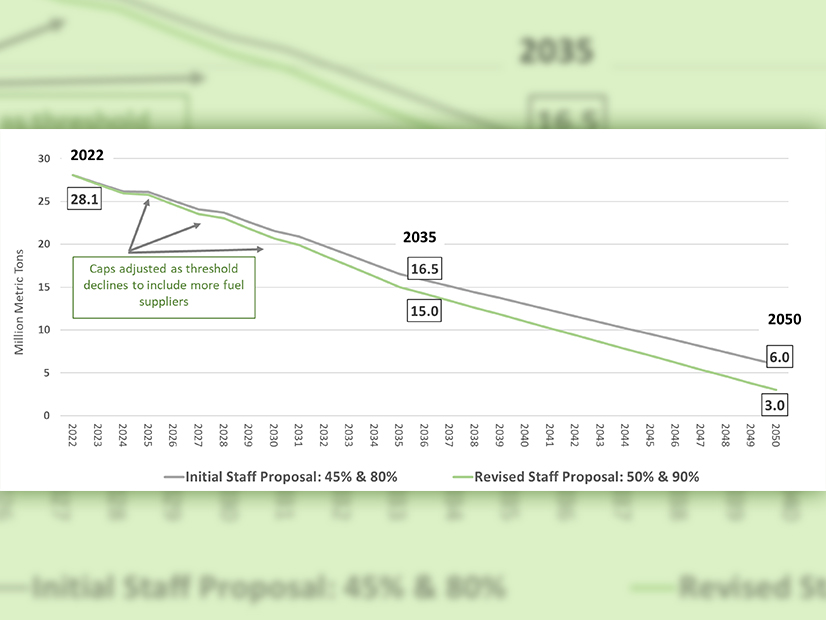

The cap program covers natural gas local distribution companies and suppliers of gasoline, diesel and propane. Starting next year, those companies will together be subject to a cumulative GHG emissions cap of 28.1 million metric tons (MMT), a figure based on the average 2017-2019 emissions from the sector.

That cap will steadily decline every year, falling to 15 MMT in 2035 and 3 MMT in 2050, compared with an earlier proposal to set the caps for those years at 16.5 MMT and 6 MMT, respectively.

Nicole Singh, DEQ senior climate change policy adviser, attributed the change to the recent release of “a lot more scienced-based” information on the need for quicker measures to stave off global temperature rise, including dire warnings from the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report in August. (See Too Late to Stop Climate Change, UN Report Says.)

Whitman said the state is now better equipped to accelerate reductions in fuel emissions after the Oregon legislature last June passed a bill requiring that all electricity delivered to customers in the state be generated by non-emitting resources by 2040. (See West Coast Could be Net Zero by Midcentury.)

“By getting us to a point where we have completely clean electricity in Oregon by 2040, that actually makes the pathway to getting into this level of reduction in GHG emissions easier than it was 18 months ago because we now have this partnership with clean electricity, and that helps us get to more aggressive levels of reduction,” Whitman said.

The cap portion of the program will be broken into three-year compliance periods, starting with the 2022-2024 interval. In the first year, companies subject to the emissions cap will be issued “compliance instruments” equal to their baseline 2017-2019 emissions levels, with each instrument entitling a holder to emit 1 MT CO2e of GHGs.

As the emissions cap declines each year, DEQ will issue fewer instruments, requiring the fuel suppliers to either reduce their emissions or acquire surplus instruments from other companies that have achieved reductions. At the end of a compliance period, each covered company must retire compliance instruments equal to their estimated obligations or face a penalty of up to $25,000 for each violation.

“There is discretion for our enforcement division to determine whether they will use the maximum extent of the fine or not,” Colin McConnaha, manager of the DEQ’s Office of Greenhouse Gas Programs, said.

Entities subject to the cap can cover a portion of their compliance obligations through the purchase of Community Climate Investment (CCI) credits. Funds from those credits will be targeted at programs that reduce emissions, promote health and accelerate the transition from fossil fuels in the state’s environmental justice communities, which include low-income areas, communities of color and rural districts.

In the first compliance period, a fuel supplier can use CCI credits to cover 10% of its compliance obligation. That figure rises to 15% in the second compliance period (2025-2027) and to 20% for 2028 and beyond.

BAER Facts

DEQ says the BAER component of the CPP will cover “certain types of facilities and certain types of emissions that cannot readily be addressed through limits on fuel suppliers, such as facilities that receive natural gas directly from an interstate pipeline (which can only be regulated by … FERC), and industrial process emissions resulting from inputs other than natural gas that are inherently part of or necessary to the product output (i.e., semiconductor manufacturing).”

The BAER rules will apply to an estimated 13 stationary sources with an annual output of 25,000 MT CO2e of emissions. Those facilities must use best available technology to limit or reduce their GHG emissions and follow a process “to periodically update those requirements to reflect technological changes.”

The new rules stipulate that a stationary source notified by the DEQ conduct a site-specific BAER assessment intended to identify strategies to reduce emissions, estimate reductions from each strategy, determine the impacts of implementing the strategies and estimate an implementation timeline.

In response to the assessment, the DEQ will issue the facility a BAER order identifying the actions required for reducing emissions — based on cost-effectiveness and technical feasibility — and setting a timeline for completion.

Many public commenters in the CPP process early on expressed concern that emissions reductions are not guaranteed under the BAER approach, asking for mandatory targets, Singh said. Singh pointed out that the final rules make clear that DEQ is not bound by a facility’s own findings in the BAER assessment.

“DEQ is allowed to use other information that’s available to us as an agency when we’re trying to make the BAER order,” she said.

Lone Dissent

The lone “no” in Thursday’s EQC vote was cast by Commissioner Greg Addington, who resides in Southern Oregon’s rural Klamath County. Addington, who acknowledged that had “checked out” of the CPP process when it went into a Rulemaking Advisory Committee about a year ago, pointed to the “vast difference” between the estimated economic impacts found in separate analyses by the DEQ and state industries.

“If I just look at employment impacts over the next 25 to 30 years, the DEQ’s report includes a gain of 20,000 jobs, and the industry’s analysis is a loss of 121,000 jobs. And that’s a big difference. Why is that so big?” Addington said.

Addington also questioned why carbon sequestration projects, which largely benefit farmers and other rural landowners, would be ineligible to receive funding from CCI credits.

“I just think this element has very little downside and sends a very positive message to a lot of parts of the state,” he said.

EQC Chair Kathleen George said the rulemaking committee did consider funding of sequestration projects, but it determined that “the most urgent action needed are concrete steps to reduce the production of greenhouse gases and to incentivize decarbonizing our energy economy.

“I just want to say I believe sequestration is of value, and while it can capture carbon, it doesn’t reduce production or change the system,” George said.