After two extremely dry years, California’s drought outlook grew more optimistic in December as major winter storms pushed mountain snowpack to 160% of average, but a rainless January and a lack of precipitation so far in February are clouding the prospects for hydroelectric generation this summer.

On Feb. 1, the state Department of Water Resources (DWR) said no snow in January meant the snowpack is now 92% of normal for the date. In the state’s Mediterranean climate, mountain snowpack typically accumulates from December to February and provides water and hydropower throughout a dry spring, summer and fall.

“We are definitely still in a drought,” DWR Director Karla Nemeth said in a statement last week. “A completely dry January shows how quickly surpluses can disappear. The variability of California weather proves that nothing is guaranteed and further emphasizes the need to conserve and continue preparing for a possible third dry year.”

DWR’s State Water Project is the fourth largest power producer in California, and hydroelectric generation historically supplies about 14% of peak summer capacity.

The state’s two largest hydropower-producing reservoirs were below half-full on Sunday. Lake Shasta stood at 36% of capacity and Lake Oroville at 46%.

The 644 MW Edward Hyatt Powerplant at Oroville Dam shut down for the first time in its history on Aug. 5 because the lake had dropped to critically low levels. After the December storms, the plant restarted one generating unit to supply electricity to CAISO’s grid.

“DWR anticipates an average outflow of about 900 cubic feet per second, which will generate approximately 30 MW of power,” the department said.

How long even that small amount of generation will last remains in doubt without additional rain and snow this year.

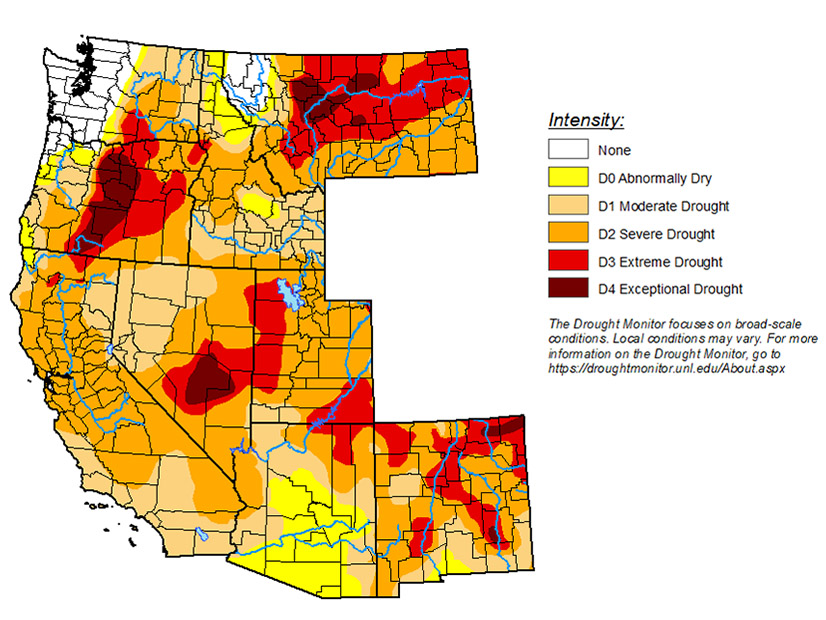

“January has turned out to be much drier than normal for most areas, essentially leveling off any meaningful gains in snowpack made in December,” the National Weather Service said Jan. 31. “A dry start to February is expected across much of the West, likely resulting in drought persistence for many areas.”

A two-decade drought in the Southwest has strained Colorado River supplies, with Lake Mead behind Hoover Dam and Lake Powell behind Glen Canyon Dam dropping so low that hydropower generation could cease. (See Western ‘Megadrought’ Curtails Hydropower and Western Drought Puts Hoover Dam Hydropower at Risk.)

California has seen two of its driest years ever.

Snow water content in California peaked at 60% of normal in 2021 after a similarly dry winter in 2020, CAISO said. The ongoing drought reduced hydropower by 1,000 MW in 2021, the California Public Utilities Commission and California Energy Commission said last summer.

‘Big Hedge’ Against Falling Hydro

This summer’s hydropower supply is questionable, CAISO CEO Elliot Mainzer said in an interview with RTO Insider on Friday.

“We’re likely to be in somewhat better condition, but there is certainly no real sign that this broader trend of drought has really abated yet,” Mainzer said.

“Everybody’s now really carefully watching what February and March are going to hold,” he said. “We still certainly have the potential for some additional precipitation … but it is going to be a critical variable.”

The addition of hundreds of megawatts of solar generation and battery storage should help alleviate a hydropower shortfall, he said. The state drove a massive scale-up in battery storage after the rolling blackouts of August 2020, adding 2,250 MW by the end of last year to store solar power for peak evening use. (See CAISO Sees ‘Explosive’ Growth in Storage in July.)

California’s energy crises in the past two summers occurred during Western heat waves, when air conditioning demand stayed high after sunset, with limited imports available.

A similar scale-up is on track this year, Mainzer said.

“Right now, by June 1, we’re anticipating an additional 2,100 MW of storage, 1,200 MW of solar, 200 MW of wind, 40 MW of hydro, 30 MW of natural gas and 11 MW of biofuels, totaling 3,581 MW, of which 2,180 MW will be available at the net peak” on hot summer evenings, he said.

“So, the big hedge against continued decline in hydro is just working as diligently as possible to get the resources that have been ordered to be procured by the California Public Utilities Commission and other regulatory authorities onto the system,” Mainzer said. “We are super focused on interconnection capacity and working with the utilities to make sure that we get those resources onto the system without delays.”